The fact that Magick is alive through the ages is remarkable. Magick has been used throughout history, in attempts to heal or harm others, to influence the weather or crops, and as part of religious practices.

While magick has been feared and condemned by those of certain faiths and questioned by scientists, it has survived both in belief and practice. Ιt is worth studying the magick through history. Uses and beliefs, from antiquity to modern times.

Ancient Mesopotamia

The ancient Mesopotamians thought that magic was the only feasible defense versus devils, ghosts, and wicked sorcerers.

To protect themselves versus the spirits of those they had actually mistreated, they would leave offerings called kispu in the individual’s burial place in intend to calm them.

If that did not work, they likewise in some cases took a figurine of the departed and buried it in the ground, requiring for the gods to remove the spirit, or require it to leave the individual alone.

The ancient Mesopotamians also used magic to safeguard themselves from evil sorcerers who may put curses on them. They had no difference in between “light magic” and “black magic” and an individual protecting him or herself from witchcraft would utilize precisely the exact same methods as the individual attempting to curse somebody.

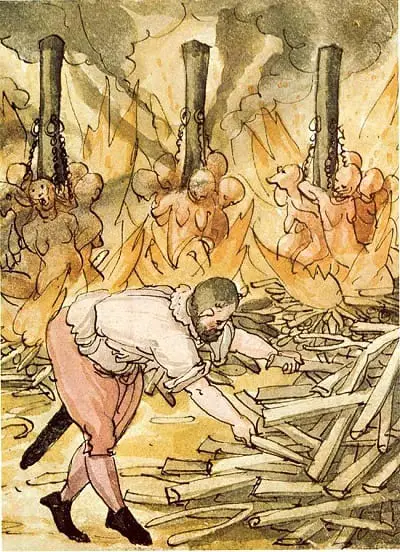

The only major distinction was the fact that curses were enacted in secret; whereas a defense against sorcery was carried out outdoors, in front of an audience if possible. One ritual to punish a sorcerer was known as Maqlû, or “The Burning”.

The individual affected by the witchcraft would develop an effigy of the sorcerer and put it on trial at night. Once the nature of the sorcerer’s crimes had actually been identified, the individual would burn the effigy and consequently break the sorcerer’s power over him or her.

The ancient Mesopotamians likewise carried out magical rituals to cleanse themselves of sins committed unconsciously. One such ritual was called the Šurpu, or “Burning”, in which the caster of the spell would move the guilt for all his or her misbehaviors onto different items such as a strip of dates, an onion, and a tuft of wool.

Such spells, which normally conjured up the help of the goddess Ishtar, were thought to trigger an individual to fall in love with another individual, restore love which had actually faded or trigger a male sexual partner to be able to sustain an erection when he had actually formerly been unable.

Other spells were utilized to conciliate a man with his patron deity or to reconcile a wife with a husband who had been ignoring her.

The ancient Mesopotamians had no difference in between “logical science” and magic. When an individual became ill, medical professionals would recommend both magical solutions to be recited as well as medical treatments.

A lot of magical rituals were planned to be carried out by an āšipu, a professional in the magical arts.

The occupation was normally given from father to son and was held in extremely high regard and typically worked as advisors to kings and great leaders.

An āšipu most likely served not only as a magician, but also as a doctor, a priest, a scribe, and a scholar. He would have likely owned a large library of clay tablets containing important religious texts and hymns.

The Sumerian god Enki, who was later syncretized with the East Semitic god Ea, was closely connected with magic and incantations; he was the patron god of the ašipū and the bārȗ and was extensively considered the ultimate source of all arcane knowledge.

Additionally, ancient Mesopotamians believed in omens, which could come upon a request or not. Despite how they came, omens were constantly taken with the utmost severity. The Mesopotamians also seem to be the inventors of astrology.

Related Reading: “Church Versus Magic in The Early Middle Ages“ – Opens in new tab

Ancient Egypt

Magic was an essential part of ancient Egyptian religious beliefs and culture. The ancient Egyptians would typically use magical amulets, referred to as meket, for protection.

The most common material for such amulets was a sort of ceramic referred to as faience, however, amulets were likewise made of stone, wood, metal, and bone.

Amulets illustrated particular signs. One of the most typical protective signs was the Eye of Horus, which represented the new eye offered to Horus by the god Thoth as a replacement for his old eye, which had been damaged throughout a battle with Horus’s uncle Seth.

The most popular amulet was the scarab beetle, the symbol of the god Khepri. Pregnant ladies would use amulets illustrating Tauret, the goddess of giving birth, to protect versus miscarriage.

The god Bes, who had the head of a lion and the body of a dwarf, was thought to be the protector of children. After giving birth, a mother would remove her Tauret amulet and place on a brand-new amulet representing Bes.

Like the Mesopotamians, the ancient Egyptians had no distinction between magic and medicine. The Egyptians thought that diseases came from supernatural origins and ancient Egyptian doctors would recommend both magical and practical treatments to their patients.

Medical professionals would question their patients to find out what conditions the person was experiencing. The symptoms of the illness figured out which deity the doctor required to invoke in order to treat it.

Doctors were exceptionally expensive, so, for most daily purposes, the typical Egyptian would have counted on people who were not expert physicians, but who had some form of medical training or understanding.

Ancient Egyptian Shamanism Diploma Course

- Certified Course

- Accredited Course

Course Information

- 10 Modules

- Lifetime Access

- Study Group Access

Use “LIGHTWARRIORSLEGION466 ” code for 70% off.

Amongst these individuals were folk healers and seers, who could set broken bones, aid moms in giving birth, proscribe natural remedies for common ailments, and interpret dreams.

Every day individuals would merely cast their spells on their own without assistance if a medical professional or seer was unavailable. Despite the fact that a lot of Egyptians were illiterate, it was commonplace for people to memorize spells and incantations for later usage.

The main concept behind Egyptian magic appears to have actually been the idea that, if a person stated something with enough conviction, the declaration would automatically end up being real.

The interior walls of the pyramid of Unas, the last pharaoh of the Egyptian Fifth Dynasty, are covered in hundreds of magical spells and engravings, running from flooring to ceiling in vertical columns.

These engravings are called the “Pyramid Texts” and they consist of spells required by the pharaoh in order to survive in the Afterlife. The Pyramid Texts were strictly for royalty only; the spells were concealed from commoners and were written just inside royal tombs.

Throughout the chaos and discontent of the First Intermediate Period, however, tomb robbers got into the pyramids and saw the magical engravings.

Commoners started discovering the spells and, by the start of the Middle Kingdom, citizens began engraving comparable writings on the sides of their own coffins, hoping that doing so would guarantee their own survival in the Afterlife. These works are known as the “Coffin Texts”.

Eventually, the Coffin Texts ended up being so extensive that they no longer fit on the exterior of a coffin. They began to be rather recorded on scrolls of papyrus, which then would be positioned inside the coffin with the deceased’s own corpse.

The writings on these scrolls are now referred to as The Book of the Dead. There were numerous various variations of The Book of the Dead, all of them including various spells.

Egyptologists have actually recognized more than four hundred various spells belonging to The Book of the Dead collectively. Egyptologists have codified and categorized these spells, assigning them specific numbers based on their content and purpose.

As The Book of the Dead became more popular, an entire industry of scribes developed for the sole function of copying manuscripts so that customers would be able to buy copies of the spells to be buried with them in their tombs.

The quality of the manuscripts was extremely variable. Some editions were ninety feet long and consisted of gorgeous, color illustrations to illuminate the text; others were short with no illustrations whatsoever. The scrolls were copied prior to they were purchased, indicating that the name of the owner was unknown.

As such, the scribes would leave the places for the person’s name blank and fill in the individual’s name after the scroll was acquired. In some cases, scribes would unintentionally misread or miscopy what they were writing.

Often the spells would be abbreviated in order to prevent running out of space. Such errors might render the texts unintelligible.

After a person passed away, his or her corpse would be mummified and covered in linen plasters in order to ensure that the deceased’s body would endure for as long as possible due to the fact that the Egyptians believed that an individual’s soul might only survive in the Afterlife for as long as his/her physical body survived here on earth.

Related Reading: The Witch Stereotype and the Crime of Witchcraft – Opens in new tab

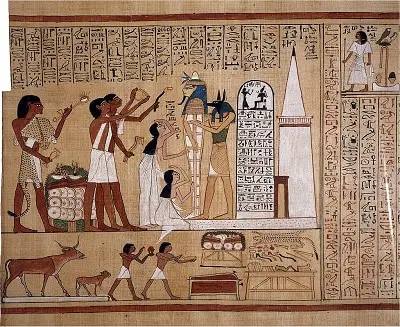

The last ceremony before an individual’s body was sealed away inside the burial place was known as the “Opening of the Mouth”. In this ritual, the priests would touch various magical instruments to numerous parts of the deceased’s body, consequently offering the deceased the ability to see, hear, taste, and smell in the Afterlife.

Prior to the dead individual was buried, his or her mummified remains would be packed complete of magic amulets and protective charms in order to make sure that he or she would be safe in the next world.

The family would likewise put important grave articles inside the person’s burial place in order to make sure that he or she had whatever she or he would require in the next life.

Among these articles were small figurines made of faience or wood known as shabti. The shabti were intended as servants for the deceased.

The ancient Egyptians thought that physical labor was just as essential in the Afterlife as it was in the present one. They thought that the deceased might cast a spell to animate these figurines so that he or she would be able to order them to carry out tasks and chores in the Afterlife so that the deceased him or herself would not be required to carry out any labor.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Classical antiquity

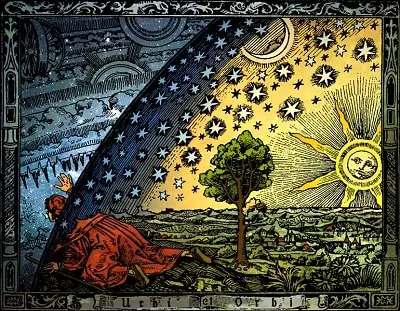

Pervasive throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Asia until late antiquity and beyond, mágos, “Magian” or “magician”, was influenced by (and eventually displaced) Greek goēs (γόης), the older word for a practitioner of magic, to include astrology, alchemy and other forms of esoteric knowledge.

This association was in turn the product of the Hellenistic fascination for (Pseudo‑)Zoroaster, who was perceived by the Greeks to be the “Chaldean”, “founder” of the Magi and “inventor” of both astrology and magic, a meaning that still survives in the modern-day words “magic” and “magician”.

In Greek literature, the earliest magical operation that supports a definition of magic as a practice aimed at trying to locate and control the secret forces of the world (physis) is found in Book X of The Odyssey (aff.link)(a text stretching back to the early 8th century BCE). Book X describes the encounter of the central hero Odysseus with the Witch Circe (Greek: Κίρκη Kírkē pronounced [kírkɛː]).

In the story, Circe’s magic consists in the use of a wand against Odysseus and his men while Odysseus’s magic consists of the use of a secret herb called moly (revealed to him by the god Hermes, “god of the golden wand”) to defend himself from her attack. In the story three requisites crucial to the idiom of “magic” in later literature are found:

- The use of a mysterious tool endowed with special powers (the wand).

- The use of a rare magical herb.

- A divine figure that reveals the secret of the magical act (Hermes).

These are the three most common elements that characterize magic as a system in the later Hellenistic and greco-Roman periods of history.

Another important definitional element to magic is also found in the story. Circe is presented as being in the form of a beautiful woman (a temptress) when Odysseus encounters her on an island. In this encounter, Circe uses her wand to change Odysseus’ companions into swine.

This may suggest that magic was associated (in this time) with practices that went against the natural order, or against wise and good forces.

Related reading: Ancient Magic: From Divine Rituals to Dark Superstitions – Ancient Rome and Early Christianity – Opens in new tab

The 6th century BCE gives rise to scattered references of magoi at work in Greece. Many of these references representing a more positive conceptualization of magic.

Among the most famous of these Greek magoi, between Homer and the Hellenistic period, are the figures of Orpheus, Pythagoras, and Empedocles.

The Hellenistic period (roughly the last three centuries BCE) is characterized by an avid interest in magic, though this may simply be because from this period a greater abundance of texts, both literary and some from actual practitioners, in Greek and in Latin remains.

In fact, many of the magical papyri that are extant were written in the 1st centuries of the Current Era, but their concepts, formulas, and rituals reflect the earlier Hellenistic period, that is, a time when the systematization of magic in the Greco-Roman world seems to have taken place

Ancient Greek scholarship of the 20th century, definitely influenced by Christianizing prejudgments of the meanings of magic and religion, and the desire to establish Greek culture as the structure of Western rationality developed a theory of ancient Greek magic as primitive and insignificant, and therefore essentially different from Homeric, communal (“polis”) religion.

Considering that the last years of the century, however, acknowledging the universality and respectability of acts such as katadesmoi (“binding spells”), described as magic by ancient and modern-day observers alike, scholars have actually been obliged to abandon this perspective.

The Greek word mageuo (“practice magic”) itself originates from the word Magos, originally merely the Greek name for a Persian people known for practicing religion. Non-civic “mystery cults” have been likewise re-evaluated.

“The choices which lay outside the range of cults did not just add additional options to the civic menu, but … sometimes incorporated critiques of the civic cults and Panhellenic myths or were genuine alternatives to them”. —Simon Price, Religions of the Ancient Greeks (1999)

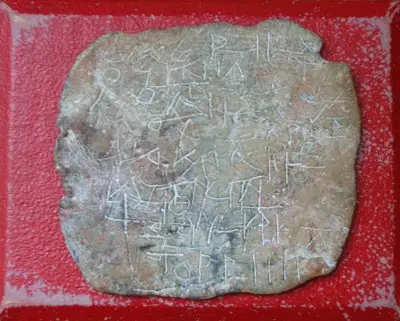

A common form of magic in ancient Greece and Rome involved invoking the chthonic deities of the underworld, using the spirits of the dead as messengers. One popular method of doing this was taking a lead tablet and inscribing it with the names of individuals that the person wished the curse.

Then the person would “cancel” the tablet by driving nails through it or by otherwise rendering it no longer usable for living beings. Such lead curse tablets were known as katadesmoi (Latin: defixiones) and were often performed by all class of Greek society, in some cases to protect the entire polis.

Communal curses performed in public declined after the Greek classical period, however, personal curses stayed common throughout antiquity. They were distinguished as magical by their individualistic, ominous, and instrumental qualities.

These qualities and their differences from the naturally changing cultural structures delineate ancient magic from the religious rituals of which they form a part.

Another common technique involved a primitive form of voodoo doll; the spellcaster would take a lead figurine with its arms bound behind its back and drive nails or needles into it, often through the breast.

The ancient Greeks often wore magic amulets to protect themselves from curses and misfortune. Amulets made from precious stones or metals were believed to be especially effective.

A great number of magical papyri, in Greek, Coptic, and Demotic, have been recuperated and translated. They consist of early instances of:

- the use of “magic words” said to have the power to command spirits

- the use of mystical signs or sigils which are thought to work when invoking or evoking spirits.

Magicians would often use secret code names for their ingredients to make them sound more foreign, exotic, and intimidating than they really were. The practice of magic was banned in the late Roman world, and the Codex Theodosianus (438 AD) states:

“If any wizard therefore or person imbued with magical contamination who is called by custom of the people a magician…should be apprehended in my retinue, or in that of the Caesar, he shall not escape punishment and torture by the protection of his rank”.

Related reading: Magic in the Age of Enlightenment: How the Seventeenth Century Redefined Magic – Opens in new tab

Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages magic in Europe took on many forms. Instead of being able to identify one type of magician, there were many who practiced several types of magic in these times, including: monks, priests, physicians, surgeons, midwives, folk healers, and diviners.

Ars Magica or magic is a major component and supporting contribution to the belief and practice of spiritual, and in a lot of cases, physical healing throughout the Middle Ages.

Originating from many modern interpretations exists a path of misunderstandings about magic, one of the largest revolving around wickedness or the existence of dubious beings who practice it.

These misinterpretations originate from numerous acts or rituals that have been performed throughout antiquity, and because of their exoticism from the commoner’s point of view, the rituals invoked uneasiness and an even stronger sense of dismissal.

Magic represented a huge threat to an age that widely professed belief in religion and holy powers.

One social force in the Middle Ages more dynamic than the simple people, the Christian Church, rejected magic in its entirety since it was considered as a way of changing the natural world in a supernatural way connected with the scriptural passages of Deuteronomy 18:9 -12.

Regardless of the various negative connotations that surround the term magic, there exist lots of parts that are viewed in a divine or holy light.

Legislation against magic could be one of two types, either by secular authorities or by the Church. The penalties assigned by secular law typically included execution, but were more severe based on the impact of the magic, as people were less concerned with the means of magic, and more concerned with its effects on others.

The penalties by the Church often required penance for the sin of magic, or in harsher cases could excommunicate the accused under the circumstances that the work of magic was a direct offense against God.

The distinction between these punishments, secular versus the Church, was not absolute as many of the laws enacted by both parties were derived from the other.

The fourteenth-century already brought about an increase of sorcery trials, however, the second and third quarters of the fifteenth century were known for the most dramatic uprising of trials involving witchcraft.

The trials developed into catch-all prosecution, in which townspeople were encouraged to seek out as many suspects as possible. The goal was no longer to secure justice against a single offender but rather to purge the community of all transgressors.

Diversified rituals or instruments used in medieval magic include, but are not limited to: many types of amulets, talismans, remedies, as well as specific incantations, dances, petitions. Together with these rituals are the negatively imbued notions of demonic participation that influence them.

The idea that magic was formulated, instructed, and worked by demons would have seemed reasonable to anyone who read the Greek magical papyri or the Sefer-ha-Razim and found that healing magic appeared together with rituals for murdering people, acquiring wealth, or personal advantage, and coercing women into sexual submission.

Archaeology is helping to a fuller understanding of ritual practices performed in the home, on the body, and in monastic and church settings.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

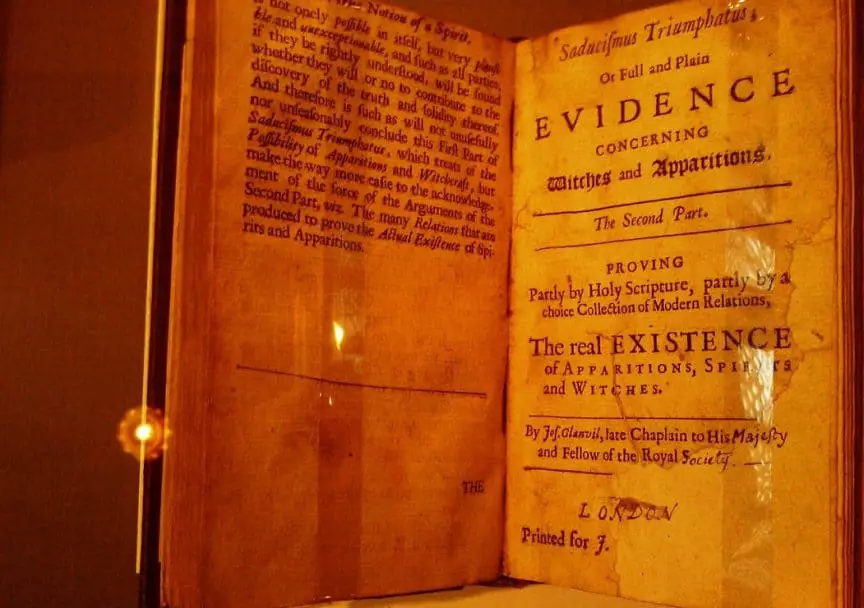

Modern Western magic

Concepts of modern magic are often greatly affected by the concepts of Aleister Crowley. Modern Western magic has actually challenged widely-held preconceptions about modern religion and spirituality.

The strongly critical discourses about magic affected the self-understanding of modern magicians, a number of whom– such as Aleister Crowley and Julius Evola– were well versed in the academic literature on the subject.

According to the scholar of religion Henrik Bogdan, ” arguably the best known epic definition” of the term “magic” of the term “magic” was offered by Crowley. Crowley– who preferred the spelling “magick” over “magic”– was of the view that “Magick is the Science and Art of causing Change to happen in conformity with Will”.

Crowley’s definition affected that of subsequent magicians. Dion Fortune of the Fraternity of the Inner Light, for instance, mentioned that “Magic is the art of altering consciousness according to Will”.

Gerald Gardner, the founder of Gardnerian Wicca, mentioned that magic was “attempting to cause the physically unusual”, while Anton LaVey, the creator of LaVeyan Satanism, explained magic as “the modification in scenarios or events in accordance with one’s will, which would be using usually acceptable techniques, be unchangeable.”

These modern Western concepts of magic rely on a belief in correspondences linked to an unidentified occult force that penetrates the universe.

As noted by Hanegraaff, this operated according to ” a new meaning of magic, which could not possibly have existed in earlier periods, precisely because it is elaborated in reaction to the “disenchantment of the world”.

For numerous, and perhaps most, modern Western magicians, the objective of magic is considered to be individual spiritual development.

The understanding of magic as a kind of self-development is central to the manner in which magical practices have actually been adopted into forms of modern Paganism and the New Age phenomenon.

One considerable advancement within modern Western magical practices has actually been sex magic. This was a practice promoted in the writings of Paschal Beverly Randolph and subsequently put in a strong interest in occultist magicians like Crowley and Theodor Reuss.

Further Reading: Check our Article “Magick – Definition and Etymology”

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Resources: Images:https://commons.wikimedia.org, Featured image:ducismus Triumphatus is in the John Rylands Library in Manchester By Victuallers https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Victuallers, https://en.wikipedia.org.