Magic has been a part of human civilization for thousands of years, existing at the crossroads of religion, science, and supernatural belief. In ancient Mesopotamia, magic was not seen as mere superstition but as a powerful tool wielded by trained experts. These specialists, known as āšipu or mašmaššu, performed rituals that combined symbolic gestures with spoken incantations to bring about tangible effects. Whether for healing, protection, or warding off evil spirits, magical practices were deeply integrated into daily life.

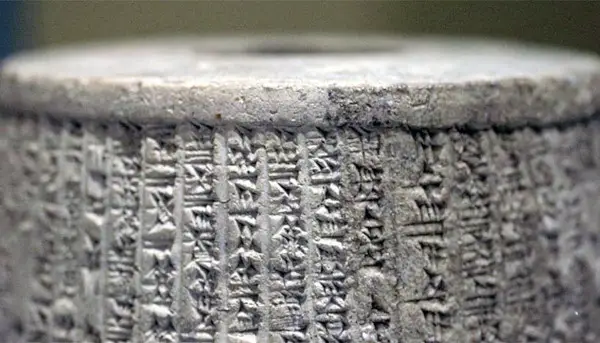

Unlike modern perceptions, Mesopotamian magic was not always considered separate from religion or science. It was a structured system of knowledge, passed down through generations, often recorded in cuneiform texts. These texts detailed complex rituals designed to interact with divine and supernatural forces. In many ways, Mesopotamian magic functioned as an early form of applied spirituality, addressing personal, social, and cosmic concerns through specialized knowledge and ritual performance.

The relationship between magic, religion, and science has long been debated. While science is based on empirical observation and repeatable experiments, and religion focuses on faith and divine worship, magic operates in a liminal space. It seeks to manipulate unseen forces through precise actions and words. The ancient world did not draw rigid boundaries between these domains. Instead, magic was a method for achieving specific outcomes, whether through divine intervention, symbolic rituals, or an understanding of natural laws that were not yet fully explained.

The Evolution of Magic in History

Magic in Mesopotamia was a highly formalized practice, deeply tied to temples, royal courts, and scholarly traditions. The āšipu were responsible for healing the sick, interpreting omens, and counteracting curses. Their knowledge was preserved in tablets found in libraries, proving that magic was an institutionalized and respected discipline. These experts operated under the belief that supernatural entities—whether gods, demons, or spirits—played a direct role in human affairs. Rituals were designed to influence these entities, ensuring prosperity, protection, or justice.

As Greek and Roman civilizations emerged, their views on magic began to shift. The Greeks borrowed the term mágos from Persian culture, initially referring to religious specialists but later applying it to individuals whose rituals were deemed suspicious or impious. Greek philosophy, particularly in the works of Plato and Aristotle, attempted to differentiate between legitimate religious practices and deceptive magical acts. Over time, mageía became associated with fraud, manipulation, and foreign religious customs. Roman authorities, in turn, regulated and often criminalized magical practices, particularly those perceived as threatening to state power.

The evolution of magic saw further transformations with the rise of Christianity. Early Christian missionaries used the term “magic” to discredit non-Christian religious practices, reinforcing its negative connotations. Magic became associated with heresy, witchcraft, and superstition, leading to periods of persecution and strict control over mystical traditions. However, despite these cultural shifts, magical practices continued to survive in folk traditions, alchemical studies, and esoteric teachings throughout history.

The Practitioners of Magic: Who Were the Magicians?

In ancient Mesopotamia, magic was not the domain of ordinary individuals. Instead, it was practiced by trained specialists who dedicated their lives to mastering the rituals, incantations, and sacred knowledge necessary to wield supernatural power. Among these experts, the āšipu (often translated as “exorcist”) and the mašmaššu held the highest authority in magical traditions.

The āšipu was more than just a sorcerer—he was a scholar, healer, and spiritual protector. His primary role was to perform rituals that counteracted malevolent forces, including demons, ghosts, curses, and divine wrath. His work often involved diagnosing the source of a person’s misfortune through divination, consulting cuneiform texts for the appropriate remedy, and performing incantations to restore balance. The mašmaššu, a term sometimes used interchangeably with āšipu, played a similar role, though his duties may have included additional religious functions within temple rituals.

These exorcists were highly educated and belonged to an elite class of temple-affiliated scholars. Their training required years of study under established masters, where they learned to read and write complex cuneiform texts, memorize long incantations, and understand the intricate relationships between gods, spirits, and human fate. Many āšipu came from hereditary lines, passing down their knowledge through generations. Their status in society was significant—they served not only the general public but also kings and high-ranking officials, ensuring their protection from supernatural threats.

Libraries and temple archives preserved vast collections of exorcists’ knowledge. The Exorcist’s Manual, a text copied by young scholars, listed the essential works an āšipu needed to master. These included purification rites, rituals to counter witchcraft, and prayers for appeasing angry deities. By controlling supernatural forces, the āšipu played a critical role in maintaining cosmic and social order.

Related reading: The Evolution of Modern Western Magic: From Ancient Mysticism to Today’s Spiritual Path – Opens in new tab

Other Magical Practitioners and Their Functions

While the āšipu was the most authoritative figure in Mesopotamian magic, he was not the only practitioner of supernatural arts. Other specialists operated on the fringes of society, offering alternative means of healing and protection.

One such figure was the asû, the physician. Unlike the āšipu, who relied heavily on incantations and divine intervention, the asû focused more on physical treatments. He prepared herbal remedies, ointments, and poultices to cure ailments, though many of these remedies were accompanied by spoken charms. The distinction between āšipu and asû was not always clear-cut—some individuals trained in both disciplines, blending medical and magical techniques.

Another important practitioner was the mušlahhu, or snake charmer. These individuals specialized in dealing with venomous bites from snakes and scorpions, which were common dangers in Mesopotamian society. Their rituals often involved reciting spells to draw out poison, invoking protective deities, and using amulets to guard against future attacks.

Other enigmatic figures included the qadištu-woman, who may have performed healing or protective rituals, and the eššebû, or “owl-man,” whose practices remain mysterious but were often linked to street magic and lower-class healing traditions. These practitioners operated outside temple authority, making their activities harder to trace in written records.

The boundaries between magic, medicine, and religion were fluid. Many healing rituals combined practical remedies with divine invocation, reflecting a worldview where illness and misfortune had both physical and supernatural causes. Whether performed by a temple-trained āšipu or a village snake charmer, magic was deeply woven into the fabric of Mesopotamian life.

Tools of the Trade: Rituals, Remedies, and Recitations

Mesopotamian magic was a carefully structured practice that blended symbolic actions with spoken words to manipulate supernatural forces. Rituals followed precise instructions, ensuring that every step—from the materials used to the gestures performed—aligned with divine and cosmic principles.

Symbolic gestures played a crucial role in these ceremonies. An āšipu might pour water over a patient to symbolize purification, break a clay figurine to represent the destruction of an enemy, or transfer a curse onto an object before discarding it. These actions were not mere theatrics; they were believed to have real power, mirroring changes in the spiritual realm.

The physical tools of the trade were equally important. Amulets, inscribed tablets, and figurines acted as conduits for magical forces. Rituals often called for the use of sacred water, special oils, plants, and minerals, each chosen for its supernatural properties. Some ceremonies required the burning of incense to carry prayers to the gods, while others used knots, cords, or wax models to bind or redirect harmful energies.

Healing and protective spells frequently incorporated food and drink, either consumed by the patient or offered to spirits to appease them. Exorcists also used fire as a purifying force—incantations like those in the Maqlû ritual burned effigies of witches to sever their influence. Whether performed in temples, private homes, or in the open air, these rituals followed a set pattern designed to bring about the desired transformation.

The Power of Words: Incantations and Prayers

Words were at the heart of Mesopotamian magic. Spoken formulas, chanted prayers, and written spells had the power to heal, curse, protect, or invoke divine intervention. These incantations, passed down through generations, were preserved in clay tablets as part of a vast magical tradition.

Sumerian and Akkadian incantations each served distinct purposes. Sumerian spells were often older and formulaic, invoking gods like Enki, the divine protector of magic. They followed structured patterns, typically describing a problem, calling upon a deity for aid, and commanding supernatural forces to act. Akkadian incantations, developed later, were more elaborate and often included mythological references to strengthen their power. These texts were commonly used in healing rituals, exorcisms, and protective charms.

Foreign-language spells also had a place in Mesopotamian magic. Words of unknown origin, sometimes resembling Hurrian or Elamite, appeared in incantations, possibly to enhance their mystical aura. Some spells used nonsense syllables—similar to modern “abracadabra”—as a way to access hidden forces beyond human comprehension. These enigmatic phrases reinforced the belief that sound itself carried magical potency.

In many cases, incantations were recited alongside ritual actions. A healer might whisper a spell over an herbal mixture, or an exorcist might chant while performing a purification rite. The repetition of sacred words ensured that the ritual was performed correctly, aligning human actions with divine will.

Related reading: Ancient Magic: From Divine Rituals to Dark Superstitions – Ancient Rome and Early Christianity – Opens in new tab

Defensive Magic: Protecting Against Harm and Misfortune

Ancient Mesopotamians believed that misfortune often stemmed from supernatural forces. Malevolent demons, restless ghosts, and powerful curses were thought to bring illness, suffering, and bad luck. These threats required intervention from an āšipu, who specialized in rituals designed to banish these entities and restore order.

Demons were considered wild, otherworldly beings that roamed deserts, mountains, and the underworld. Some, like Lamaštu, attacked infants and pregnant women, while others, such as Pazuzu, were paradoxically both feared and used for protection against more dangerous spirits. These entities could slip into homes through doors and windows, causing disease and misfortune. To counter their influence, exorcists performed rituals that invoked protective deities, used fire to purify spaces, and placed apotropaic figurines—small protective statues—at entrances to guard against intrusion.

Ghosts, particularly those of the unburied or improperly honored dead, were also a source of supernatural harm. If a deceased family member did not receive regular offerings, their spirit might linger, causing disturbances or sickness. To send ghosts back to the underworld, exorcists performed ceremonies that involved making figurines of the deceased, feeding them ritual meals, and sending them away on miniature boats. In more severe cases, rituals involved invoking Šamaš, the sun god and divine judge, to ensure the spirit found peace.

Curses, whether inflicted through witchcraft or divine displeasure, were another major source of distress. A person suffering from a curse might experience sudden misfortunes, unexplained illnesses, or deteriorating mental health. Unlike random bad luck, curses were believed to be deliberate acts of harm, requiring specialized rituals to reverse their effects.

Undoing Curses and Divine Wrath

Curses often resulted from breaking taboos, violating sacred spaces, or offending a deity. Mesopotamians believed that divine punishment could manifest in the form of sickness, failure, or even death. To undo these afflictions, two of the most powerful purification rituals—Šurpu and Maqlû—were performed.

The Šurpu ritual, meaning “incineration,” was used to break curses and remove guilt. The afflicted person confessed their possible transgressions, which were symbolically transferred onto ritual objects—often a peeled garlic bulb, representing the shedding of the curse. These objects were then burned, washing away the negative effects. The ritual also included prayers to Šamaš, asking the sun god to clear the person’s fate.

The Maqlû ritual, or “burning,” was the most extensive anti-witchcraft ceremony in Mesopotamian magic. It targeted individuals believed to have used sorcery to harm others. Over the course of an entire night, exorcists recited powerful incantations, created clay figurines representing the witches, and destroyed them in fire. By transferring the harm back onto the sorcerer, this ritual ensured that the victim was freed from magical oppression.

These rituals were not merely symbolic; they were elaborate performances involving water purification, fire cleansing, and offerings to gods. The combination of spoken incantations and physical destruction of ritual objects reinforced the belief that curses could be lifted and divine wrath appeased.

Check out our recommendations at “Occult Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Library“

The Power of Purification and Protection

Purification rituals played a vital role in Mesopotamian life, ensuring individuals, homes, and temples remained free from harmful forces. Water was the primary cleansing agent, used in ceremonies where an āšipu would sprinkle or pour it over the afflicted person while reciting prayers. Special washing rites, like Bīt Rimki (“The Bathhouse”) and Bīt Mēseri (“The House of Confinement”), were performed to cleanse individuals of spiritual contamination before major religious ceremonies.

Beyond ritual purification, protection against future harm was a key concern. Amulets and apotropaic figures were commonly placed in homes, worn as jewelry, or buried at important locations. Figurines of protective deities, such as Pazuzu, were used to ward off Lamaštu and other malevolent forces. Temples and palaces also had guardian statues placed at entrances to keep evil spirits at bay.

These protective measures were not only for the elite—common households also used small clay amulets, charms, and simple purification rituals to maintain security. Whether through elaborate temple ceremonies or personal household practices, defensive magic was a fundamental part of Mesopotamian life, ensuring that people remained safe from the unseen dangers of the spiritual world.

The Darker Side of Magic: Controlling Others

While much of Mesopotamian magic focused on protection and healing, some rituals were designed to manipulate others for personal gain. Love spells, influence rituals, and courtroom magic provided individuals with supernatural ways to control emotions, thoughts, and actions. Unlike defensive magic, which was widely accepted, these aggressive magical practices existed in a gray area—powerful yet potentially dangerous.

Love spells were particularly common, used to attract or bind a romantic partner. These rituals often involved crafting figurines, anointing objects with magical oils, or reciting incantations under specific astrological conditions. Some spells sought to make a lover irresistibly drawn to the practitioner, while others aimed to bring back a lost partner. Women and men alike turned to these methods, believing that supernatural forces could enhance their desirability or sway the affections of another.

Beyond love, Mesopotamians also used magic to gain influence in court and political settings. An āšipu might prepare spells to ensure success when addressing a king, appearing before a judge, or negotiating a deal. Specific rituals, such as “seizing the mouth” (ka-dab-be₂-da) and “soothing the anger” (šur₂-hun-ga₂), were designed to control conversations and make one’s words more persuasive. Some incantations were even used to silence rivals, ensuring that an opponent would fumble or fail in a critical debate.

While these spells offered advantages, they carried risks. Misusing magic to control others could be seen as sorcery, leading to accusations of witchcraft. Nevertheless, as long as a ritual did not directly harm another person, it remained an accepted part of Mesopotamian life, used by both elites and commoners seeking an edge in love, politics, or business.

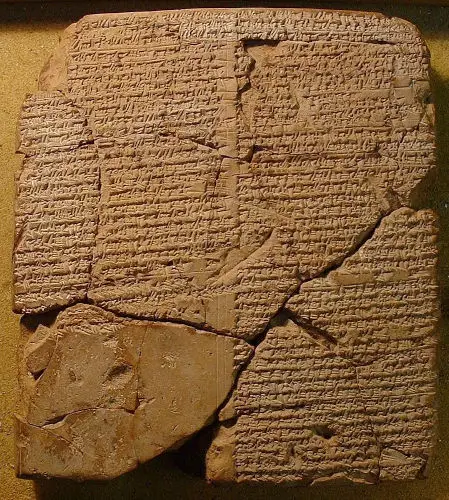

The British Museum, London. (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Magic for Power and Prosperity

Wealth and success were as desirable in ancient Mesopotamia as they are today. Magic was frequently used to improve business prospects, attract customers, and ensure financial stability. Merchants, tavern owners, and craftsmen turned to spells and rituals to enhance their fortunes, believing that divine intervention could bring prosperity.

One recorded ritual, aimed at increasing business, involved placing enchanted objects near a shop’s entrance to lure in customers. Special incantations were whispered over beer or food, ensuring that customers would keep returning. Similar spells were used by innkeepers, invoking spirits to make their establishments more inviting.

Personal charisma and dominance were also sought through magic. Individuals looking to rise in social or political ranks used rituals to increase their attractiveness, confidence, and presence. Some spells called upon divine favor, ensuring that a person would be noticed and admired by their peers. Others focused on weakening rivals, creating magical barriers to prevent their success.

These aggressive magical practices highlight the deeply practical nature of Mesopotamian occult traditions. Whether seeking love, influence, or wealth, people turned to magic as a tool for advancement, blending the mystical with the everyday struggles of human ambition.

Related reading: Beyond the Shadows: How Occultism Shaped Politics, Science, and Social Change – Opens in new tab

Witchcraft and Forbidden Magic: When Magic Becomes a Crime

In ancient Mesopotamia, magic was a double-edged sword. While exorcists and healers used rituals for protection, healing, and success, not all magical practices were seen as legitimate. Sorcery—magic intended to harm others—was feared and condemned, often leading to accusations, trials, and severe punishments.

Witchcraft, or kišpū, was believed to cause illness, misfortune, and even death. Unlike defensive or beneficial magic, which sought to restore balance, sorcery was considered an attack against an individual’s well-being. A sorcerer might use figurines to represent their victim, burying them to symbolically entrap the target or burning them to cause suffering. Spells could also be cast over food, drink, or personal belongings to transfer curses directly.

The fear of malevolent magic led to strict laws against witchcraft. The Code of Hammurabi, one of the oldest known legal codes, prescribed the death penalty for convicted sorcerers. If someone accused another of witchcraft without proof, they themselves could be executed—highlighting the seriousness of such claims. Other legal records describe trials in which accused witches had to swear their innocence before the gods or undergo ritual ordeals to determine their guilt.

Despite these harsh consequences, accusations of witchcraft were not uncommon. People blamed unexplained illnesses, sudden deaths, and financial ruin on hidden enemies working through sorcery. This fear extended to the highest levels of society—kings and nobles sought the services of exorcists to ensure that they were not under magical attack.

The Rituals to Counter Witchcraft

Given the fear surrounding sorcery, Mesopotamian exorcists developed extensive rituals to counteract its effects. The āšipu was the primary defense against witchcraft, performing ceremonies that identified, neutralized, and reversed harmful magic.

One of the most powerful anti-witchcraft rituals was Maqlû (“Burning”). This all-night ceremony involved reciting a long series of incantations while crafting and destroying effigies of the suspected sorcerers. These figurines, made of clay or wax, were burned in fire, symbolizing the destruction of the witch’s power. The ritual also called upon gods like Šamaš, the divine judge, to punish the guilty while purifying the victim.

Protective spells were another common defense. Individuals often wore amulets or placed apotropaic figurines in their homes to ward off sorcerers. Some charms invoked deities like Ea, the god of wisdom, who was believed to grant protection against harmful spells. Special incantations could also be recited over water or oil, which was then used to wash away the effects of witchcraft.

Exorcists played a crucial role in fighting sorcery, not only performing these rituals but also diagnosing witchcraft-induced ailments. By interpreting omens, consulting texts, and examining symptoms, they could determine whether a curse was at work. If sorcery was suspected, a ritual would be performed to sever the magical connection between the victim and the witch, ensuring their recovery.

Witchcraft was one of the greatest supernatural fears in Mesopotamian society. While magic was widely accepted as a part of life, its misuse was seen as a dangerous crime—one that could be met with both divine and legal punishment.

Related reading: Burning Words, Healing Bodies: How Medieval England Used Written Words to Heal – Opens in new tab

The Effectiveness of Magic: Success, Failure, and the Magical Experience

In ancient Mesopotamia, magic was more than just a set of rituals—it was a fundamental part of how people understood the world. Misfortune, illness, and even political upheaval were not seen as random events but as consequences of supernatural forces at work. Magic provided a way to restore balance, offering comfort and a sense of control in an unpredictable world.

Magical rituals carried deep psychological and cultural significance. The elaborate steps, sacred words, and carefully chosen materials reinforced the belief that these ceremonies were effective. People trusted in the power of trained exorcists and healers, whose knowledge of ancient texts and divine connections gave them authority. The very act of performing a ritual—whether it involved purification, burning an effigy, or invoking protective deities—helped individuals feel that action was being taken against unseen threats.

Societal beliefs also shaped the perception of magic’s effectiveness. If someone recovered after a healing ritual, it was seen as proof of the power of magic. If a curse was lifted and misfortunes ceased, it confirmed the success of the exorcist’s work. Word of these successes spread, reinforcing trust in magical practices and ensuring their continued use for generations.

Even kings and high-ranking officials relied on magic, consulting exorcists before making decisions or seeking divine protection from enemies. This widespread acceptance meant that magic was not an isolated or fringe practice—it was deeply woven into everyday life, influencing medicine, politics, and religious observance.

When Magic Fails: Explanations and Justifications

Despite its widespread use, magic did not always produce the desired results. People still fell ill, crops failed, and disasters struck. But failure did not shake the belief in magic—it simply required an explanation.

One common justification was that the ritual had been performed incorrectly. Magical ceremonies relied on precise wording, gestures, and materials. A single mistake, such as mispronouncing an incantation or using the wrong offering, could render the spell ineffective. If failure occurred, the ritual might be repeated with greater care, ensuring that all steps were correctly followed.

Another explanation was that the magical forces opposing the ritual were too strong. If an enemy sorcerer had cast a powerful curse, it might require multiple rituals to counteract their work. In some cases, divine intervention was needed—an exorcist might invoke a higher deity to overcome an especially resistant affliction.

Fate and divine will also played a role in magical success. Sometimes, a person’s suffering was believed to be a form of divine punishment, and no ritual could reverse it until the gods had been appeased. In such cases, additional offerings, prayers, or acts of penance were recommended. If a king or noble suffered misfortune despite protective spells, it was often interpreted as a sign that the gods had a greater plan at work.

Even when magic did not produce immediate results, the experience itself was powerful. Rituals provided reassurance, helping people process misfortune and feel spiritually cleansed. They strengthened social bonds, reinforcing the authority of priests and exorcists while maintaining a sense of order in an uncertain world.

For the ancient Mesopotamians, magic was never a question of if it worked—it was a question of why it worked, how to use it correctly, and what greater forces might be influencing the outcome.

End Words

Magic in ancient Mesopotamia was more than superstition—it was a structured, deeply ingrained system that shaped how people understood and navigated their world. From protective rituals and healing spells to aggressive magic and witchcraft accusations, these practices were a fundamental part of daily life, blending science, religion, and supernatural belief.

Exorcists, physicians, and other magical practitioners held significant roles in society, offering solutions to ailments, misfortune, and unseen threats. Whether through purification ceremonies, incantations, or apotropaic objects, magic provided both psychological comfort and tangible results. Even when spells failed, explanations rooted in divine will or ritual errors ensured that faith in magic remained unshaken.

Ultimately, Mesopotamian magic was a tool for survival, empowerment, and order in an unpredictable world. Its legacy, seen in later mystical traditions, continues to reflect humanity’s enduring desire to influence fate and protect against the unknown.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Source: “Magic Rituals: Conceptualization and Performance.” By Daniel Schwemer

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Featured image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.