Witchcraft is a broad term for the belief and practice of magic. It can be found in various cultures across history and means something slightly different to every group.

It is estimated that tens of thousands of people were convicted of being witches and executed by hanging, burning, or drowning during the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Most supposed witches were usually old women, and invariably poor. Any who were unfortunate enough to be crone-like, snaggle-toothed, and sunken-cheeked were assumed to possess the Evil Eye.

If they also had a cat, red hair, the ‘devil’s mark’, or being left-handed, it was further proof. Many unfortunate women were condemned to this sort of evidence and hanged after undergoing appalling torture.

So here we have 5 amazing witchcraft cases that you need to know.

Mother Shipton

Mother Shipton was born Ursula Sontheil in 1488, during the reign of Henry VII, father of Henry VIII. Although little is known about her parents, legend has it that she was born during a violent thunderstorm in a cave on the banks of the River Nidd in Knaresborough.

Her mother, Agatha, was just fifteen years old when she gave birth, and despite being dragged before the local magistrate, she would not reveal who the father was.

With no family and no friends to support her, Agatha raised Ursula in the cave on her own for two years before the Abbott of Beverley took pity on them and a local family took Ursula in. Agatha was taken to a nunnery far away, where she died some years later. She never saw her daughter again.

Ursula grew up around Knaresborough. She was a strange child, both in looks and in nature. Her nose was large and crooked, her back bent and her legs twisted. Just like a witch.

She was taunted and teased by the local people and so in time, she learnt she was best off on her own. She spent most of her days around the cave where she was born. There she studied the forest, the flowers and herbs and made remedies and potions with them.

When she was twenty-four she met a young man by the name of Tobias Shipton. He was a carpenter from the city of York. Tobias died a few years later before they had any children, but Ursula kept his name, Shipton. The Mother part followed later when she was an old woman.

As well as making traditional remedies, Mother Shipton had another gift. She could predict the future. It started off with small premonitions but as she practiced she became more confident and her powers grew.

Soon she was known as Knaresborough’s Prophetess, a witch. She made her living telling the future and warning those who asked of what was to come. After a long life, she died in 1561, aged 73.

Since the mid-17th century, there have been more than fifty different editions of books about Mother Shipton and her prophecies, some purporting to tell her life story in considerable detail.

One of the earliest accounts was said to have recorded the sayings of Mother Shipton, as told to a Joanne Waller, who died soon afterward at the great age of ninety-four. That would mean Joanne, as a young girl, had listened to the old lady not long before her death in 1561.

Although we cannot be sure how much of the legend is true, what must be certain is that 500 years ago a woman called Mother Shipton lived here in Knaresborough and that when she spoke people believed her and passed her words on.

The prophecies may not be all historically correct and the stories may have been embellished slightly over the centuries, but she remains one of those legendary figures of romance and folklore entwined in our imaginations and the local surroundings.

Prophecies

The most famous claimed edition of Mother Shipton’s prophecies foretells many modern events and phenomena. Widely quoted today as if it were the original, it contains over a hundred prophetic rhymed couplets in notably non-16th-century language and includes the now-famous lines:

- Then upside down the world shall be And gold found at the root of tree All England’s sons that plough the land Shall oft be seen with Book in hand The poor shall now great wisdom know Great houses stand in far-flung vale All covered o’er with snow and hail.

- A carriage without horse will go, Disaster fills the world with woe. In London, Primrose Hill shall be In center hold a bishops sea.

- Around the world, men’s thoughts will fly, Quick as the twinkling of an eye. And water shall great wonders do, How strange, and yet it shall come true.

- Through towering hills, proud men shall ride, No horse or ass move by his side. Beneath the water, men shall walk, Shall ride, shall sleep, shall even talk.

- And in the air men shall be seen, In white and black and even green. A great man, shall come and go For prophecy declares it so.

- In water, iron then shall float As easy as a wooden boat. Gold shall be seen in stream and stone, In land that is yet unknown.

- Three times shall lovely sunny France Be led to play a bloody dance. Before the people shall be free Three tyrant rulers shall she see.

- For in those wondrous far off days, The women shall adopt a craze To dress like men, and trousers wear And to cut off all their locks of hair. They’ll ride astride with brazen brow, As witches do on broomsticks now.

- I know I go, I know I’m free, I know that this will come to be, Secreted this, for this will be Found by later dynasty.

- Mother Shipton’s last prophecy: When pictures seem alive with movements free, When boats like fishes swim beneath the sea. When men like birds shall scour the sky. Then half the world, deep drenched in blood shall die.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Eleanor Cobham Duchess of Gloucester

Born around 1400 and probably at the castle of Sterborough in Kent, Eleanor Cobham was the daughter of Sir Reginald Cobham of Sterborough and his wife Eleanor, daughter of Sir Thomas Culpeper of Rayal.

As is often the case with Medieval women, nothing is known of Eleanor’s early life. She appeared at court in her early 20s, when she was appointed lady-in-waiting to Jacqueline of Hainault, Duchess of Gloucester.

Jacqueline had come to England to escape her 2nd husband, the abusive John IV Duke of Brabant. She obtained an annulment of the marriage from the Antipope, Benedict XIII, and married Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, in 1423. He would spend a large amount of their marriage trying to recover Jacqueline’s lands from the Dukes of Brabant and Burgundy.

Humphrey Duke of Gloucester

Humphrey was a younger brother of King Henry V and John, Duke of Bedford. He had fought at the Battle of Shrewsbury at the age of 12 years and 9 months and would go on to fight at Agincourt in 1415.

On Henry V’s death, Humphrey acted as Regent for his young nephew, Henry VI, whenever his older brother, the Duke of Bedford, was away fighting in France. However, he seems to have been little liked and was never trusted with full Regency powers.

In 1428 Pope Martin V refused to recognize the annulment of Jacqueline’s previous marriage to John of Brabant and declared the Gloucester marriage null and void.

However, John of Brabant had died in 1426 and so Humphrey and Jacqueline were free to remarry – if they wanted to. In the meantime, Humphrey’s attention had turned to Eleanor of Cobham and he made no attempt to keep Jacqueline by his side.

This did not go down too well with the good ladies of London, who petitioned parliament between Christmas 1427 and Easter 1428.

According to the chronicler Stow their letters were delivered to Humphrey, the archbishops and the lords “containing matter of rebuke and sharpe reprehension of the Duke of Gloucester, because he would not deliver his wife Jacqueline out of her grievous imprisonment, being then held prisoner by the Duke of Burgundy, suffering her to remain so unkindly, contrary to the law of God and the honorable estate of matrimony”.

Humphrey paid the petition little attention and married Eleanor sometime between 1428 and 1431. It has been suggested that Eleanor was the mother of Humphrey’s two illegitimate children – Arthur and Antigone – although this seems unlikely as Humphrey made no attempt to legitimize them following the marriage (as his grandfather John of Gaunt had done with his Beaufort children by Katherine Swynford).

Described by Aeneas Sylvius as “a woman distinguished in her form” and “beautiful and marvelously pleasant” by Jean de Waurin, Eleanor and Humphrey had a small but lively court at their residence of La Plesaunce at Greenwich. Humphrey had a lifelong love of learning, which Eleanor most likely shared, and the couple attracted scholars, musicians, and poets to their court.

On 25th June 1431, as Duchess of Gloucester, Eleanor was admitted to the fraternity of the monastery of St Albans – to which her husband already belonged – and in 1432 she was made a Lady of the Garter.

Eleanor’s status rose even higher in 1435, with the death of John Duke of Bedford. Whilst Henry VI was still childless, John had been heir presumptive. He died having had no children and so the position passed to Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester.

With her heightened status, Eleanor received sumptuous Christmas gifts from the king; and her father was given custody of the French hostage Charles, Duke of Orleans – a prisoner since Agincourt.

Related Reading: “Medieval Persecution of Magic – The Inquisition and the inquisitor’s profile“– Opens in new tab

But in 1441 came Eleanor’s dramatic downfall.

Master Thomas Southwell, a canon of St Stephen’s Chapel at Westminster, and Master Roger Bolingbroke, a scholar, astronomer and cleric – and alleged necromancer, were arrested for casting the King’s horoscope and predicting his death.

Southwell and Bolingbroke, along with Margery Jourdemayne, known as the Witch of Eye and renowned for selling potions and spells, were accused of making a wax image of the king, ‘the which image they dealt so with, that by their devilish incantations and sorcery they intended to bring out of life, little and little, the king’s person, as they little and little consumed that image’.

Bolingbroke implicated Eleanor during questioning, saying she had asked him to cast her horoscope and predict her future; for the wife of the heir to the throne, this was a dangerous practice. Did she have her eye on the throne itself?

On hearing of the arrest of her associates, Eleanor fled to Sanctuary at Westminster. Of 28 charges against her, she admitted to 5. Eleanor denied the treason charges but confessed to obtaining potions from Jourdemayne in order to help her conceive a child.

Awaiting further proceedings, as Eleanor remained in Sanctuary, pleading sickness, she tried to escape by the river. Thwarted, she was escorted to Leeds Castle on 11th August and held there for 2 months.

Having returned to Westminster Eleanor was examined by an ecclesiastical tribunal on 19th October and on the 23rd she faced Bolingbroke, Southwell, and Jourdemayne who accused her of being the “causer and doer of all these deeds”. (Related reading: Paganism in Medieval Europe)

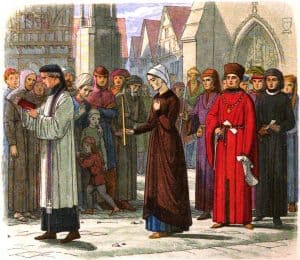

Eleanor was found guilty of sorcery and witchcraft; she was condemned to do public penance and perpetual imprisonment. Of her co-accused; Bolingbroke was hanged, drawn and quartered, Southwell died in the Tower of London and Margery Jourdemayne was burned at the stake at Smithfield.

Eleanor’s own chaplain, Master John Hume, had also been arrested, although he was accused only of knowledge of the others’ actions and was later pardoned.

On 3 occasions Eleanor was made to do public penance at various churches in London; on the 1st of such, 13th November 1441, bareheaded and dressed in black carrying a wax taper, she walked from Temple Bar to St Paul’s Cathedral, where she offered the wax taper at the high altar.

Following 2 further penances, at Christ Church and St Michael’s in Cornhill, Eleanor was sent first to Chester Castle and then to Kenilworth. Her circumstances much reduced, Eleanor was allowed a household of only 12 persons.

Eleanor’s witchcraft conviction discredited her husband; Humphrey was marginalized and on 6th November 1441 his marriage was annulled. Humphrey’s enemies, Margaret of Anjou (Henry VI’s queen) and the Earl of Suffolk, convinced the king that his uncle was plotting against him.

In February 1447, Humphrey was arrested and confined in Bury St Edmunds. He died a week later, on 23rd February; some claimed it was murder, but the most likely cause of death is a stroke.

Eleanor was moved to Peel Castle on the Isle of Man, in 1446 and one final time in 1449 when she was transferred to Beaumaris Castle on Anglesey.

Eleanor Cobham, one time Duchess of Gloucester and wife to the heir to England’s throne, having risen so high – and fallen so low – died still a prisoner, at Beaumaris Castle on 7th July 1452; she was buried at Beaumaris, at the expense of Sir William Beauchamp, the castle’s constable.

Related reading: Burning Words, Healing Bodies: How Medieval England Used Written Words to Heal – Opens in new tab

Agnes Waterhouse

Agnes Waterhouse (1503 – 1566) was the first woman executed for witchcraft in England.

When the law condemning witchcraft came into effect, Agnes was in her 40s. She may have been born in 1503, although her early life wasn’t well documented.

She lived in Hatfield Peverel, Essex, England. To local people, she was known as Mother Waterhouse. This nickname suggests her position in society – perhaps as a single woman, who was generally seen as compassionate and helpful.

She may have been a healer and wise woman. Her life was calm and normal until 1566 when she was accused of witchcraft along with two other women – Elizabeth Francis and Joan Waterhouse (Agnes’ daughter.)

The trial against Agnes took place in Chelmsford, Essex. The actual trial notes are confusing, but what it boils down to is this:

Elizabeth Francis confessed to having a familiar- a cat named Satan (Sathan). She received the cat from her grandmother- who taught her witchcraft as a child.

Elizabeth had a close relationship with Satan (Sathan) and it spoke to her in exchange for drops of blood. She also said the cat helped her kill people, terminate pregnancies, and instructed her to steal cattle.

Here’s the best part- Elizabeth gave Agnes the cat in exchange for cake. Priorities, priorities. Agnes tested the cat’s witchy abilities and had it kill one of her pigs. After arguing with her neighbors- she had him kill their cows and geese.

Joan Waterhouse testified next- she confessed to giving it a whirl with Satan when her mother was out. At this point in the story- Satan had transformed himself into a toad. When Joan was refused food from a neighbor’s child- Satan the toad offered to help in exchange for her soul.

Joan agreed to the deal- and the toad, now a dog with horns, harassed the child. This child, in turn, testified that the black dog with horns asked her for butter and when she refused, Satan promised she would die.

When the child asked who the master’s “dame” was- he indicated that it was, in fact, Agnes Waterhouse. And this was the evidence that convicted poor Agnes. Toads, butter, dogs, horns, a child’s word.

On 29 July 1566 – two days after the trial finished – Agnes Waterhouse was executed. At this time she repented and asked for forgiveness from God. She also confessed to her attempt to send the cat, Satan, to hurt and damage the goods of her neighbor, the tailor named Wardol.

However, this was unsuccessful because he was so strong in faith. She was also questioned about her church habits. Agnes Waterhouse said that she prayed often, but always in Latin because the cat, Satan, forbid her from praying in English. (Related reading: Paganism in Medieval Europe)

Agnes Naismith

The Paisley witches, also known as the Bargarran witches or the Renfrewshire witches, were tried in Paisley, Renfrewshire, central Scotland, in 1697.

Christian Shaw …“an 11-year-old girl, the daughter of the Laird of Bargarran, accused seven or eight people of tormenting her”

“As the months went on, she developed all sorts of symptoms. Flying in the air. Coughing up bits of hair, coal, and all sorts of different things.

“Eventually, they decided there was witchcraft involved. And they went to a trial.”

Αgnes Naismith holds a prominent place in the story, given that she was accused alongside Katherine Campbell at the beginning of Christian Shaw’s malady.

Various local sources tell us that she probably resided in Kilpatrick, on the other side of the river from Bargarran house. According to the story, Naismith was the key individual who was responsible for the child’s descent into illness, and it would seem she had a relationship of sorts with the maid Katherine Campbell.

Agnes Naismith was an elderly woman, impoverished, with a reputation in the local area for being someone who you did not cross lightly.

Naismith would have been a regular visitor to Bargarran House, as well as other steadings in the local region, in search of food and materials to help her in her daily life. It is likely that she existed on the margins.

On the 21st of August 1696, just four days after Katherine Campbell had cursed the young girl, Naismith arrived at Bargarran house, very early in the morning. The story goes that she found Christian Shaw in the courtyard with her younger sister.

Naismith then asked after Christian Shaw’s health, and what her age was. Both pieces of information were given freely. Her visit would not have been an unusual event for Christian Shaw, who would have been accustomed to people approaching the house for food at a time when pressures on the land meant that more people were seeking charity. Apparently, Naismith did not wait for alms on this occasion.

The next evening, Christian Shaw experienced her first fit. She was said to have flown over her bed and into a bystander in her bedchamber.

She suffered excruciating pains, became paralyzed, before convulsing violently. These symptoms continued for eight days. Soon, the child was blaming Naismith for cutting her side and tormenting her.

Naismith’s recent visit to the house would have been remembered, as would her questions to the child. Naismith was summoned to Bargarran House twice to answer to the charges. Without being asked to do so, Naismith prayed for the young girl’s health to improve.

Once she had done this, Christian Shaw declared that Naismith no longer tormented her. Indeed, the girl claimed that Naismith began to buffet her from the worst of the assaults from her other invisible tormentors.

Despite this, Naismith was found guilty due to the weight of witness evidence against her at the trial. She was deemed responsible not only for the bewitching of Christian Shaw, but of being one of the more important members of the local crew of witches that were said to be terrorizing the area.

She never confessed to this charge, even to the end. Just before she was hanged, it is said that she laid a curse on all those who stood witness to her execution. Naismith’s curse can be directly linked to the horseshoe that was laid some years later. Even in death, her legacy continues.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

The North Berwick Witch Trials

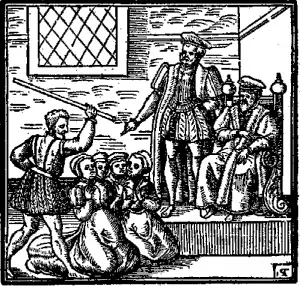

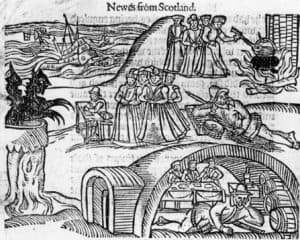

During the reign of King James VI, somewhere between 70 and 200 so-called witches were put on trial, tortured and even executed, from the town of North Berwick and the surrounding area alone.

The exact number is not known, and neither is the proportion of those arrested who were actually executed. However, the consensus is that the large majority were horrifically tortured. The reason for this was King James.

James VI was traveling to Denmark to collect his new bride Anne of Denmark in 1589. During the crossing, the storms were so severe that he was forced to turn back.

James became convinced that this was the work of witches from North Berwick, intent on his ruin. There was a talk at the time that one of them had sailed into the Firth of Forth on a sieve to summon the storm, thus dually proving her guilt as not only a witch, but also as a would-be regicide.

James’ hatred and obsession of witches and witchcraft became well known. It was no accident that Shakespeare wrote the witches in Macbeth during the reign of King James in the early 17th Century, in fact, the North Berwick Witch’s adventure in the sieve is even mentioned in the play. In the opening scene of the play, Shakespeare’s First Witch cries

“But in a sieve, I’ll thither sail

And, like a rat without a tail,

I’ll so, I’ll do, I’ll do”

At which point they promise to conjure up a storm. This does seem a very unlikely coincidence; it is clear James’ disdain for witches had spread countywide. James had been King of Scotland after his mother Mary Queen of Scots abdicated in 1567, although regents ruled on his behalf until he came of age in 1576.

James became King of England in 1603 on the death of Elizabeth 1 and appears to have continued to be fascinated by the dark arts: releasing his best-selling book, ‘Daemonologie’, which explored the areas of witchcraft and demonic magic, shortly after assuming the throne.

However, Scotland was where he began his crusade against this supposed daemonologie. The witch trials of North Berwick are particularly noteworthy due to the sheer number of ‘witches’, the consensus being around 70, that was tried from such a tiny and seemingly insignificant town in Scotland, on this single occasion.

Scotland itself saw about 4,000 people burned alive at the stake for witchcraft, an enormous number relative to its size and population. Something else that is remarkable about the North Berwick witch trials was the bizarre nature of the accusations and the despicable forms of torture used to extract confessions from the victims.

The fact that James could have been so convinced that the storm that stymied his plans had been conjured by some Scottish women is incredibly hard to believe. However, around 70 individuals, mostly women, were duly rounded up, tortured and put on trial, some in North Berwick, some in Edinburgh.

There was a church on the green where the witches were said to hold their covens, dance and summon the devil.

This was St. Andrews Kirk, situated on the seafront. It would have been a perfect place from which to summon storms!

In fact, there were rumors that some of the witches were held, tortured and eventually tried on the grounds of the Kirk, the foundations of which exist even today.

Although not recorded it is generally accepted that many victims died of the injuries that were inflicted upon them during torture.

Some of the implements of torture that were used at the time included the breast ripper. A device that did exactly as it sounds. It consists of 4 pronged levers that would encase the breast of the accused ‘witch’ and then tear it from her chest with a considerable amount of trauma.

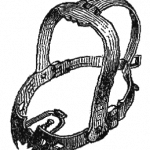

Another device that was used on witches either already tried or awaiting trial was the ‘Scold’s Bridle’. A metal device that fits around the head and had metal protrusions that would slide into the victim’s mouths making it impossible to talk. Sometimes men would use these devices on errant wives who nagged them too often. But they were often used on witches.

Several measures were used to detect witchcraft but you could be accused simply for having red hair, for having an unusual ‘devil’s mark’ or what we would call a birthmark, or for being left-handed.

The word sinister actually comes from the Latin ‘sinistra’ which means left. Traditionally older women and those who worked with herbs and medicines or midwives would also be targeted. (Related reading: Paganism in Medieval Europe)

Among the witches accused at North Berwick for trying to murder James were Agnes Sampson, a well-known midwife and Gellie Duncan, a healer.

Gilly (or Gellie) Duncan, from the small town of Tranent near Edinburgh had been arrested for suspected witchcraft after some of her healing cures were branded as miraculous and the work of a witch.

Initially, Gellie obstinately refused to confess to any dealings with the Devil but, after protracted torture and after the discovery of a so-called “Devil’s mark” on her neck, she confessed to being a witch and having sold her soul to the Devil, and effecting all her cures by his aid.

Under further torture, she named various accomplices, including Dr. John Fian (a local schoolmaster and alleged coven leader and wizard), Agnes Sampson (a respected local midwife and healer), Barbara Napier (the widow of Earl Archibald of Angus), Francis Stewart (the 1st Earl of Bothwell, and the King’s cousin) and Euphemia Maclean (the daughter of the Lord Cliftonhall). Ultimately, Gilly was burned at the stake.

Many confessed under torture to having met with the Devil in the North Berwick churchyard at night, and to devote themselves to doing evil, including attempts to poison the King and other members of his household, and to sink the King’s ship.

Specific confessions claimed that, on Halloween of 1590, the Devil had the witches dig up corpses and cut off different joints or organs which were then attached to a dead cat and thrown into the sea in order to call up the storm which had nearly shipwrecked the King’s ship.

Some attested that the Devil had incited them to these acts because he considered King James his greatest enemy (an admission that James found particularly flattering). The confessions were all suspiciously similar and were all extracted by torture.

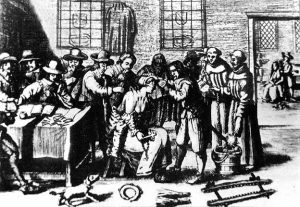

One particularly gruesome account was that of Agnes Sampson, who was examined by King James himself at his palace of Holyrood House.

She was fastened to the wall of her cell by a “witch’s bridle”, an iron instrument with four sharp prongs forced into the mouth so that two prongs pressed against the tongue, and the two others against the cheeks.

She was kept without sleep, thrown with a rope around her head, and only after these ordeals did Agnes Sampson confess to the fifty-three indictments against her. She was finally strangled and burned as a witch.

Dr. Fian, a schoolmaster at Tranent and a pretender at magic, was also tortured extensively, with the rack and “the boot”, as well as having his fingernails pulled out with pincers and having needles inserted into his fingernails. Crippled and bloodied from torture, he nevertheless only signed a confession due to trickery.

James VI was in many ways an admirable monarch; he started the first postal service in the UK, a progenitor to what became the Royal Mail. He foiled the Gunpowder Plot and saved Parliament and he translated what became a definitive version of The Bible that is still used today.

But when it came to witches he had a peculiar blind-spot and was both irrational and cruel. It is unimaginable to adequately comprehend the torture and pain that the accused witches would have endured only to be burned for crimes they could never have committed.

However, their brutal deaths are not forgotten and are still talked about in this small seaside town today. This fitting Memento Mori to the North Berwick Witches remains in the grounds of St Andrew’s Kirk to this day.

This was the first major witchcraft persecution in Scotland. It is estimated that between 3,000 and 4,000 accused witches may have been killed in Scotland over the years from 1560 to 1707.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Featured Image: The Witch Hunt-Henry Ossawa Tanner