Excluding the well-known, great Greek woman philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria, hardly the most could be called another. But the history of women in philosophy is longer than you might suppose.

They were present in most of the schools of Greek philosophy and with their influence contribute to the development of Greek philosophy throughout antiquity.

Here are 7 female Greek philosophers you need to know.

Arete of Cyrene ( 400 BCΕ– 340 BCΕ)

Arete of Cyrene lived in a city in North Africa, in what is now the nation of Libya, but at the time that Arete lived, it was part of the great Greek Empire. She was an educated woman and philosopher and the only ancient women of that period who had an actual career in philosophy.

There is a legend about the name of the city. According to the myth, Cyrene was a nymph, the daughter of Hypsesus, who was king of the Lapiths, and Chlidanope, who was a Naiad. The Greek god Apollo found Cyrene wrestling alone with a lion, fell in love with her, and took her off to Mount Pelion. Later he founded a city which he named after her and made her its queen.

Ηistorically the city was actually founded in approximately 631 BC by a group of people from the island of Thera.

Cyrene became one of the most important intellectual centers of the classical world and included some of the best of all academic pursuits, including a well-known medical school, scholars as the geographer Eratosthenes and of course the father of Arete, Aristippus, who was the founder of the Cyrenaic school of philosophy.

Arete was born in a time period in which Cyrene was powerful, wealthy and has an advanced academia. Her father certainly helped her to gain as much education as she could.

So, it was natural for her to choose a career in philosophy. Her father had raised her to be egalitarian, prudent and practical and to detest excess of any kind.

Aristippus left Cyrene for Athens because he had heard of Socrates and his dialogues and he became one of his close friend and student. He was one of the men who wandered around Athens with Socrates as that great philosopher asked the people questions to reveal their ignorance.

After his return in Cyrene, he founded the Cyrenaic school of philosophy. He was also one of the few philosophers who accepted money for philosophical guidance, which is something that Arete continued as she became an instructor.

At those times, women were not allowed to attend public forums, but Plato’s school still welcomed women into its ranks. Arete took advantage of that and attended as many private meetings as possible.

She was very active in all philosophical dealings, helping to spread the ideals of the Cyrenaic School as widely as possible.

She was a good example of the principles of the Cyrenaic school and therefore was the proper follower to lead the school after her father died.

Cyrenaics, as they were called, believed that ethics was the principal part of philosophy. They were deeply concerned in anything that was good for the family, and society.

Check out books on Greek Philosophy– opens in new tab

The only measure they had for morality was the pleasure, as it was the pleasure that they believed to be the purpose of life. They proposed that people should never postpone a pleasure at hand in hopes of a future one, but should grab, enjoy, and appreciate the pleasures that came to them.

The Cyrenaic School was one of the first schools to have a basis in hedonism. Although their idea of hedonism was not based on an acquisition of possessions or the selfish pursuit of pleasure at the expense of all others.

Arete of Cyrene had a son, who she named like her father, Aristippus. According to the customs of her times, she had to hire tutors to teach him.

Instead, Arete taught him herself, hence her son was nicknamed, “mêtrodidactos” “Mother-Taught” (Greek: Μητροδίδακτος). He also became a philosopher and it appears that he was the person who codified much of the philosophy of the Cyreniac School.

Arete of Cyrene spent 33 years of her life teaching natural and moral philosophy. She published many documents, but most of them have been lost over time. She was considered to be a star among female philosophers of her time. That was the reason why upon her tomb was inscribed an epitaph that stated that she was:

“The splendor of Greece and that she possessed the beauty of Helen, the virtue of Thirma, the soul of Socrates, and the tongue of Homer”.

Check out our recommendations at “Philosophy Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Library“

Hipparchia of Maroneia (350BCE – 280BCE)

Hipparchia of Maroneia ( Greek: Ἱππαρχία ἡ Μαρωνεῖτις) was a Cynic philosopher and wife of Crates of Thebes.

Hipparchia was born into an aristocratic family in Maroneia, in Thrace around 346 BCE. She was known for her intellectual curiosity, her lack of interest in household chores and her independent public behavior.

She had a basic education in subjects such as reading and music. This knowledge would give her the ammunition to stand on her own intellectually later in her life.

Her family came to Athens, where Hipparchia’s brother, Metrocles, became a pupil in Aristotle’s Lyceum and later began to follow Crates of Thebes, the most famous Cynic philosopher in Greece at that time. So, she may have been introduced to philosophy by her brother.

Hipparchia began to follow Crate’s teachings. She not only wanted to study with him but fell in love with him, despite his notorious ‘poor looks’ and the fact that he was an old man at the time. She was so keen to marry him that she threatened to kill herself rather than live in any other way.

Her parents begged Crates to dissuade her and he tried to do so. When he failed to convince her, he disrobed in front of her and said, “this is the groom, and these are his possessions; choose accordingly.”

But Hipparchia was not discouraged. Despite the disapproval of her parents, she married Crates (a convention that was not popular among the Cynics) and went on to live a life of Cynic poverty on the streets of Athens with her husband.

She adopted the Cynic life getting the same clothes that he wore and appearing with him in public. In doing so she acted according to Cynic’s idea of changing culture and politics by one’s life and action.

The Cynics were a group of philosophers who claimed to come from Socrates. They attempted to live “according to nature” by rejecting artificial social conventions and refusing all luxuries, including any items not absolutely required for survival.

They gave up their belongings, carrying what few they needed in a pouch. They wore only a simple cloak, and begged to receive their basic needs. Crates’ willingness to marry was also unusual since marriage is a social institution of the kind normally rejected by Cynics. After all, earlier Cynics like Diogenes and Antisthenes had argued that the philosopher would never marry.

While no existing writings are directly attributed to Hipparchia. Most of our knowledge about Hipparchia comes from anecdotes and sayings repeated by later authors, emphasizing both her direct, Cynic rhetoric and her nonconformity to traditional gendered roles.

Hipparchia’s behavior was bold and independent in public. Diogenes Laertius describes a public encounter with Theodorus the Atheist, a well-known thinker of the day, who had challenged the legitimacy of her presence at a symposium.

According to Diogenes Laertius, Theodorus quoted a verse from Euripides’ Bacchae and said to her:

“Who is the woman who has left behind the shuttles of the loom?”

And Hipparchia replied:

“I, Theodorus, am that person, but do I appear to you to have come to a wrong decision if I devote that time to philosophy, which I otherwise should have spent at the loom?”

Check out books on Cynic Philosophy– opens in new tab

In the ancient Greece women of her social class typically would have been occupied with weaving and organizing the household servants. In that cultural context, Hipparchia’s rejection of the conventional expectations for women was quite radical.

Diogenes Laertius also reports the syllogism that Hipparchia used to put down Theodorus during the same symposium mentioned above:

Assertion A: “Any action which would not be called wrong if done by Theodorus, would not be called wrong if done by Hipparchia.”

Assertion B: “Now Theodorus does no wrong when he strikes himself”.

Conclusion: “Therefore neither does Hipparchia do wrong when she strikes Theodorus.”

This is a classic example of the Cynic rhetorical trope of “spoudogéloion” (Greek: σπουδογέλοιον): a deliberately comic syllogism which nevertheless makes a serious point.

Diogenes Laertius says that since Theodorus “had no reply wherefore to meet the argument,” he “tried to strip her of her cloak. But Hipparchia showed no sign of alarm or of the perturbation natural in a woman”, as a result to her Cynic commitment to “anaideia“ (Greek: Ἀναιδεία)( shamelessness – without embarrassment). According to the principle of “Anaideia”, any act sufficiently virtuous to be done in private is virtuous enough to be done in public.

Hipparchia had at least two children, a daughter, and a son named Pasicles. We don’t know the date and how she died.

The ancient Greek poet Antipater of Sidon wrote the following epigram for Hipparchia: “I, Hipparchia, chose not the tasks of amply-robed woman, but the manly life of the Cynics. Nor do tunics fastened with brooches and thick-soled slippers, and the hair-caul wet with ointment please me, but rather the wallet and its fellow-traveler the staff and the coarse double mantle suited to them, and a bed strewn on the ground. I shall have a greater name than that of Arcadian Atalanta by so much as wisdom is better than racing over the mountains.”

A genus of butterflies, Hipparchia, bears her name.

Check out our recommendations at “Philosophy Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Library“

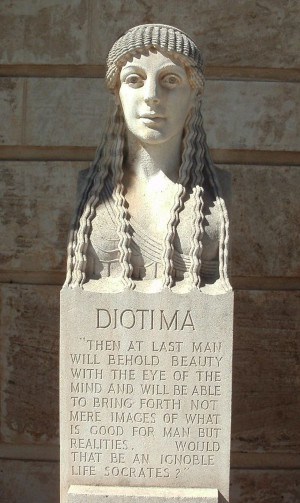

Diotima of Mantinea (circa 440 B.C.E)

Diotima of Mantinea (Greek: Διοτίμα) was a female philosopher and a High priestess of the Mystery religions of Greece. The name Diotima means “honored by Zeus”.

She was from the Peloponnesian city of Mantinea, which allied itself with Sparta during the Peloponnesian War.

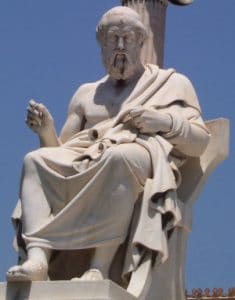

Her existence is known through the work of Plato “Symposium”, where Socrates recognizes Diotima as his Teacher, admitting that he owes his knowledge and his views on Love, which has nothing to do with carnal attraction or earthy motives, but it is the motivation and the quest for anything that is beautiful and true.

The words of Socrates to his associates dominate the dialogue with Diotima, transferring them all that was previously taught by the Arcadian Philosopher. In a dialogue that Socrates recounts in the Symposium, she explains Love in all its variants including Divine Love.

It is interesting that Socrates, the one who is the role model of the “philosopher”, is the person who introduces the ideas of a woman philosopher.

As High priestess to the Eleusinian Mysteries Diotima had an extremely important role. She was not merely a female Hierophant. She was the “Goddess” herself that has gone through all stages of the spiritual path and has become a goddess.

Only someone in this unique position was able to help others through this final stage of the spiritual path towards Annihilation. The role has always been that of the woman and was perhaps the most important role in the Mysteries.

Diotima appears to have been an extremely powerful and gifted Priestess, a healer as well as a teacher. Therefore, Socrates claims that Diotima successfully postponed the Plague of Athens.

Check out books on Greek Philosophy– opens in new tab

Perictione (5th century BCE)

Perictione (Greek: Περικτιόνη ) was born around 425BCE in Athens. She was a descendant of Solon, the greatest Athenian lawmaker who replaced the actual Draconian laws with more humane ones.

She was the sister of Charmides and the niece of Critias, who was two powerful members of the infamous Thirty Tyrants who ruled Athens after its defeat in the Peloponnesian War. Perictione was one of the teachers of Socrates and the mother of his greatest student, Plato.

She was born into an aristocratic family and she was highly educated. Her first husband was Ariston of Collytus (a descendant of King Codrus). They had four children. Three were three sons, Adeimantus, Glaucon, Plato and a daughter named Potone.

Not many years after Plato’s birth, Perictione widowed. At the time, according to the law, a widow could choose to return to her father’s house, to live with one of her sons or to remarry.

So, she married her uncle, Pyrilampes. He was her mother’s brother and prominent supporter of Pericles who had served an ambassador to the Persian court.

During this second marriage, Perictione gave birth to a son, Antiphon, the half-brother of Plato, additionally Pyrilampes had a son from his previous marriage (Demus). Perictione was widowed for a second time, but this time she went to live with her eldest son.

As a mother, Perictione had a great influence on Plato’s thoughts as well, which were shaped mainly from Socratic teachings. Many historians argue that Perictione was behind the thought of Plato to permit women to join his school, Academy.

Perictione would visit Socrates often or invite him to their home in Athens, where often debated among themselves their diverse beliefs and thoughts. The ancient Greek historian, Diogenes Laertius mentions that Perictione influenced some Socratic thoughts.

The friendship between Perictione and Socrates developed over the years. To an extent, Perictione visited Socrates when he was in jail on charges of rebellion against Athens.

She tried to use her acquaintances in order to save him from the death penalty. She also met Socrates on the day he was executed, while some sources claim she was present till his last breath.

Perictione wrote two treatises, “The Harmony of Women” and “On Wisdom”. Briefly, the first concerns the duties of a woman to her husband, her marriage, and to her parents, and the second is a blend of her thoughts combined with some Socratic principles on the philosophical definition of wisdom.

Among historians seems to be a confusion about Perictione. Some contend that the work “The Harmony of Women” was not authored by Perictione, the mother of Plato. They claim, extant fragments of “The Harmony of Women” were written in Ionic Greek language commonly used in the 4th and 3rd Century BCE while the other treatise, ‘On Wisdom’, is written in Doric Greek, which was used much later.

Maybe there was another woman thinker and philosopher with the same name much later than the mother of Plato. For distinction, historians named the earlier thinker as Perictione I and the later one as Perictione II.

Another group believes that these treatises wrote by some male followers of Pythagoras who used the name “Perictione” as a pen name.

We don’t know the specific date of Perictione’s death. From various sources, it seems she died around 385 BCE at the age of 80.

Themista of Lampsacus (371 – 271 BCE)

Themista of Lampsacus (Greek: Θεμίστη) was one of the most prominent followers of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus, and the wife of Leonteus.

Epicurean philosophy promoted some of the most practical, rational and simple precepts for someone who wanted to acquire a happy and successful life. Epicurus in his school, allowed women to attend, that was quite unusual in the 3rd century BCE. Leontion also attending Epicurus’ school around the same time.

Themista was one of the first women in history who wrote a book of philosophy. Her book, “The Vanity of Glory” was quite influential in antiquity. It is known that several hundred years after her death, Cicero quoted from her book in a speech before the Roman senate. Her influence persisted into the Christian era.

She was called the female Solon, and Epicurus dedicated a number of his works to her. Cicero ridicules Epicurus for writing “countless volumes in praise of Themista,” instead of more worthy men such as Miltiades, Themistocles or Epaminondas.

Themista and Leonteus named their son Epicurus.

Check out our recommendations at “Philosophy Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Library“

Lasthenia of Mantinea (c. 325 BCE)

Lasthenia of Mantinea (Greek: Λασθένεια της Μαντινείας) was one of Plato’s female students at the Academy. Lasthenia was born in Mantinea a Greek city-state in Acadia, Peloponnese, into a wealthy family and went to Athens to study philosophy.

Ancient Athens had two free social classes, Citizens and Metics (foreigners living in Athens), and a slave class. Lasthenia was a ‘free woman of the metic class’.

A woman in Ancient Athens had very little independence, as it was considered to be outside of the social class system.

However, they were respected as caregivers and home managers. They had no place outside of the home and they belong in whatever group your husband or father was.

No woman could live on her own. If her husband died, his will could set herself and her dowry to another citizen of his choice. If there was no will, she could return to her father’s home or in some cases marry again – often to a widower relative.

If her second husband died, she could, if she chose, go to live with one of her grown sons. But under no circumstances could a woman citizen live alone.

The ‘Metics women’ who came to Athens from other city-states were in a different situation. While they could live on their own, the law did not protect them at all.

As a result, many developed affairs with Athenian citizen men in order to secure their protection. But Lasthenia of Mantinea chooses a different way. Instead of seeking an Athenian male citizen as friend and protector, she dressed in men’s clothing and openly attended the Academy of Plato.

The reason for that wasn’t to deceive Plato. It is well known that Plato accepted women into his academy and appreciated the potential of the female intellect. But to avoid scandal and whatever negative publicity might spoil the reputation of the Academy among those not intimately associated with Plato’s circle.

After the death of Plato, she continued her studies with Plato’s nephew, Speusippus. Some sources also report that she had a relationship with Speusippus.

Check out our recommendations at “Philosophy Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Library“

Theano of Crotona (500 BCE)

Theano (Greek: Θεανώ) was born in Crotona at 546 BCE (some says in Crete). She was the daughter of a physician named Brontinus. She had a superior education, which was a common tradition among the rich and famous of her times. She was a very beautiful and intelligent woman.

Her father, Brontinus, was an Orphic disciple. Orphic main beliefs were around the death and resurrection of the Egyptian god Osiris. They believed in reincarnation and the afterlife.

Pythagoreans were inspired by Egyptian tradition as well. So, it is not surprising that Brontinus and Theano became disciples of Pythagoras.

Pythagoras moved to the Greek colony of Croton in southern Italy around 531 BC. There Pythagoras established his academy dedicated to the mathematical and philosophical study of the nature of the universe.

In addition, the students of the academy were taught techniques about self-control, self-esteem, and self-awareness and other studies related to spiritual life.

He accepted men and women on an equal basis. There are indications that out of 300 disciples in total, at least 28 were women.

He was 56 years old and Theano was 36 years younger but she was full of passion for science. She spent several hours with Pythagoras, discussing issues such as theories on mathematics, the universe, and mystical sciences.

Eventually, they married and brought five children to life, three daughters, Damo, Myia and Arignote and two sons, Mnesarchus and Teleuges.

When Pythagoras’s academy gained influence on the government of Croton, the locals considered it as a threat and decided to destroy it. Pythagoras and many other teachers and students were killed.

After Pythagoras’ death Theano, with the support of her children, became the head of Pythagoras’ school. She and her children, all of whom were philosophers, continued the Pythagorean academy.

Not only kept the school and its doctrines alive, but they were also central to the spread of Pythagorean thought. Without the work of Theano and her children, Pythagorean thought and brotherhood would most likely not have so much influence in the ancient world.

Theano wrote many treatises which include, “Life of Pythagoras”, “The Construction of the Universe”, “Cosmology”, “Theory of the Golden Mean”, “Theory of Numbers” and “On Virtue.”

The book, ‘On Virtue’ explicitly deals with marriage and family psychology. None of these writings have survived except a few fragments and letters of uncertain authorship.

Αccording to historians Theano passed away due to natural causes in old age, in Crotona. She had her children and other disciples with her and may have been buried near her school.

Many women who follow her path to science and philosophy during ancient times, like Hypatia of Alexandria, perhaps had influenced by her works.

Check out books on Greek Philosopher Pythagoras– opens in new tab

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Featured Image By Pixabay.