In ancient times, magic was seen as a powerful and influential force, not just a source of entertainment or illusion. It held a serious role in society, deeply intertwined with religious and supernatural beliefs. The word “magic” itself, derived from the Greek mageía (μαγεία) and the Latin magia, had already transformed from its original meaning in ancient Persia.

Initially, it referred to religious priests performing rituals for the supreme god Ormuzd. However, by the time the Greeks encountered these practices, magic had become associated with mysterious, often feared powers believed to influence the natural world.

Magic was not a standalone concept. It was connected to the divine and the mysterious forces beyond human control. The supernatural element of magic is what gave it such a commanding presence in society. People believed magicians could communicate with gods or otherworldly spirits to influence events in the physical world, whether for good or evil.

The Role of Magic in Daily Life: More Than Just a Belief

For the people of ancient Rome and Greece, magic wasn’t just an abstract idea—it was a significant part of daily life. It was believed that magicians held private powers capable of changing the course of events.

Magic could be used for a variety of purposes, from protecting crops to ensuring good fortune, to more sinister uses like harming enemies. Apuleius, a famous Roman writer, described magicians as individuals who could interact with the immortal gods and use their powers to achieve their desires.

This belief in magic permeated all levels of society, affecting the common folk and elites alike. Ordinary people feared the destructive potential of magic and often turned to spells or rituals for protection.

On the other hand, the elites sometimes saw magic as a threat to social order, especially when it came to “black magic,” which was associated with malicious intent. Whether for personal gain, protection, or harm, magic had a real and tangible influence on how people lived their lives.

Transition from Religion to Superstition

In the Roman world, the line between religion and magic was often blurred. The Romans practiced religio, which referred to the official worship of the gods, a key part of public life. This was seen as proper devotion, ensuring the gods would look favorably upon them.

However, anything outside of this structured worship was often labeled as superstitio, meaning superstition. Magic, especially when practiced in secret or outside official channels, was quickly categorized as superstition.

This shift from religion to superstition happened as magic began to be viewed with suspicion. Rituals that weren’t part of the state-sanctioned religious calendar were seen as dangerous. Magic, in this context, was perceived as an attempt to manipulate the gods for selfish purposes rather than worshipping them with respect.

It became associated with foreign practices, hidden ceremonies, and darker forces. Magic was no longer a form of communication with the gods; it was an illicit power that sought to bend supernatural forces to the magician’s will.

Magic and Its Place in Ancient Belief Systems

In the ancient world, magic was not seen solely as a mystical practice but as both an art (τέχνη) and a science. It involved precise rituals, knowledge of natural elements, and an understanding of the supernatural.

Magic was used to explain the unexplainable—filling the gaps where science had yet to provide answers. Ancient practitioners believed they could manipulate natural forces through spells, potions, and ceremonies to achieve specific outcomes.

Magic was intertwined with medicine, astrology, and religion, blending the boundaries of practical knowledge and mystical power. While it wasn’t fully accepted by the state, it was undeniably part of daily life.

The Mystery Schools of Egypt and Their Influence on Magic

Egypt played a key role in shaping ancient magical practices, and its mystery schools were at the heart of this influence. These schools, often located in temples, were centers of learning where priests studied astronomy, medicine, and esoteric knowledge. Egyptian magicians were considered some of the most skilled in the ancient world, and their understanding of magic had a profound effect on neighboring cultures, including Greece and Rome.

These mystery schools taught that magic could be used to interact with the divine. Egyptian rituals often involved invoking gods and spirits, and these practices spread throughout the Mediterranean, becoming integral to Greco-Roman magic. Egypt’s reputation for advanced magical knowledge made it the go-to place for those seeking to enhance their own abilities or learn the secrets of the supernatural.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

How Magic Was Used to Gain Power and Control

Magic in ancient times was not just about spiritual exploration—it was also a tool for gaining power and control. Many magicians used their skills to manipulate others, enhance their influence, or protect themselves from enemies.

Political leaders and elites often sought out magicians for personal protection or to ensure success in battle. The belief that magic could change fate or grant special favors made it a powerful asset in the ancient world.

In Roman society, magic was especially feared when used for harmful purposes, known as maleficium. This type of dark magic aimed to harm others, often for personal gain. Those who practiced such rituals were seen as threats to public order, and the legal system treated magic as a crime when it crossed into the realm of poisoning or treachery. Magic wasn’t merely a personal practice—it had far-reaching social and political implications.

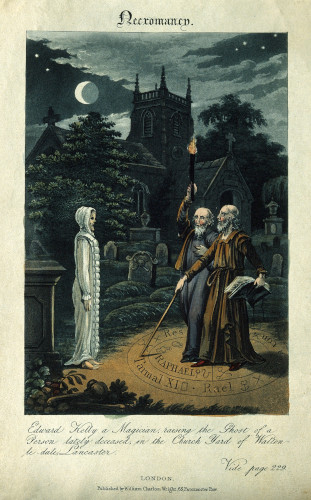

Necromancy and Dark Rituals: A Look at Erichto and Simon

Necromancy, the practice of communicating with the dead to predict the future, was one of the darkest and most feared forms of magic. It was often associated with powerful figures like the Thessalian witch Erichto (Ἐριχθώ), who featured prominently in Lucan’s Pharsalia.

Erichto was known for her grotesque rituals, which involved desecrating tombs and performing spells to raise the dead. Her actions were seen as crossing moral and religious boundaries, making her a symbol of forbidden and dangerous magic.

Simon Magus, another figure linked to dark rituals, was infamous for his use of necromancy and other forms of illicit magic. According to Christian sources, Simon manipulated spirits and invoked demonic forces to gain power. Like Erichto, Simon’s practices were condemned by the state and the early Church, which viewed these dark arts as a direct threat to social and religious order.

Both figures highlight the ancient fascination with, and fear of, magic that delved into the afterlife and the unseen forces of the underworld. Their stories serve as reminders of how necromancy and dark rituals stood at the fringe of accepted practice, both feared and sought after by those desperate for control over life and death.

The Magician in Roman Society

Magic in Roman society can trace its origins back to the ancient Persian priests, known as magi. These magi were religious figures who conducted rituals for the benefit of Ormuzd (Ahura Mazda), the supreme god in Zoroastrianism.

When the Greeks encountered the magi after the Persian Wars, they began to associate their rituals—often filled with strange chants and mysterious symbols—with otherworldly powers. As these practices spread into Rome, the concept of magic transformed. What began as religious duties in Persia became a misunderstood and feared practice in the Roman world, often linked to dark or forbidden powers.

This blending of Persian religious rituals with Roman and Greek beliefs about the supernatural created a complex and evolving understanding of magic. As it moved westward, magic in Rome became something to be both revered and feared, laying the foundation for its role in Roman society.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images (CC BY 4.0)

How the Term “Magician” Evolved Over Time

The term “magician” underwent a significant transformation as it moved through different cultures. Originally, in the Avestan language, magus referred to a priest responsible for sacred rituals.

However, by the time the term reached Greece and Rome, it had lost its religious connotations and became synonymous with individuals who could tap into supernatural forces. In fact, it described someone capable of using secret, often forbidden, knowledge to manipulate these forces.

By the Roman period, a magician was often seen as someone working outside the bounds of proper religious practice, using hidden powers for personal gain. Magicians were both respected and feared for their ability to invoke unseen forces, but they also occupied a precarious position within society.

While some aspects of their work were tolerated, others—especially when it came to darker, more malicious forms of magic—were deemed illegal and dangerous.

Apuleius and the Power of Magic in the Roman Age

The writings of Apuleius, a 2nd-century Roman philosopher, give us valuable insights into how magic was perceived during the Roman Empire. In his famous work Apology, Apuleius describes magicians as individuals with the power to communicate directly with gods and use their strength to achieve whatever they wished. This image of the magician as an omnipotent figure who could alter the course of fate and life was deeply ingrained in the Roman mindset.

Apuleius himself was accused of practicing magic, illustrating just how seriously the Romans took these accusations. His defense against these claims provides a rare glimpse into the mindset of the time. Apuleius claimed that in Persian culture, a magician was simply a priest, but in Rome, the term had taken on a much darker and more dangerous meaning. This shift shows how magic had evolved from a respected religious practice to something that could potentially threaten public safety and order.

Magic vs. Religion: The Thin Line Between Sacred Rituals and Superstition

In Roman society, the distinction between magic and religion wasn’t always clear. The Roman state upheld religio as the official form of worship, comprising legally sanctioned rituals and sacrifices to the gods. These rituals were seen as essential for maintaining the favor of the gods and ensuring the prosperity of the state.

On the other hand, superstitio was regarded as irrational and excessive religious behavior, often involving foreign or unsanctioned practices. Magic, especially when it didn’t align with state-approved religion, quickly fell into this category.

The key difference lay in the purpose and execution of the rituals. While Roman religion focused on honoring the gods to maintain harmony, magic sought to control or manipulate the gods and other supernatural forces for personal gain.

Magicians were seen as dangerous because they attempted to bend divine power to their will, often in secret or for harmful purposes. This conflict between legitimate religion and suspect superstition created tension within Roman society, as both practices relied on similar elements—rituals, chants, and offerings—but had very different goals.

Related reading: The Evolution of Modern Western Magic: From Ancient Mysticism to Today’s Spiritual Path – Opens in new tab

The Roman Calendar and Magic’s Role in Religious Practices

In Roman society, religion was strictly regulated by the state, with rituals and sacrifices carefully prescribed according to the official calendar. These events were seen as necessary for maintaining the favor of the gods and ensuring the prosperity of the Roman Empire. The state took great care to differentiate between sanctioned religious practices and unsanctioned magical rituals.

Despite this, certain magical practices still found their way into Roman life, especially those that seemed to complement official religion. For example, the Carmen Arvale was a traditional chant intended to protect crops and promote a good harvest.

Though this might seem like a religious act, it closely resembled magical spells meant to secure divine favor. Roman authorities allowed such rituals when they supported the community, but private acts of magic for personal gain were viewed with suspicion and often outlawed.

Magic, especially when it aligned with accepted practices, became part of everyday life. However, anything that deviated from the Roman calendar’s established rituals risked being labeled as dangerous or criminal superstition.

The Dark Side of Magic: Superstition and Fear

Magic in ancient Rome wasn’t just regarded as a mystical force; it was feared because of its association with malevolent power. While some magical practices, such as protective spells, were tolerated, darker forms of magic—especially those intended to harm or control others—were seen as a direct threat to the social order. This form of magic, often referred to as maleficium, was believed to bring illness, death, and chaos.

Romans viewed magic as a force capable of polluting both the mind and body of its victims. This fear was deeply rooted in the idea that magic could manipulate the unseen forces of the supernatural for destructive purposes.

The secrecy surrounding magical practices, often performed at night or in hidden places, only heightened this anxiety. The idea that a person could be attacked through invisible means by a magician’s spell made magic a constant source of fear in both public and private life.

Black Magic and Its Impact on Roman Law

Black magic, or harmful magic intended to manipulate or injure others, became a significant issue for Roman lawmakers. As these practices grew in prominence, they were increasingly linked to criminal behavior, including poisoning, political subversion, and social unrest. The elite, in particular, feared the power of magic, believing that it could be used to undermine their authority or harm their family members.

The fear of black magic became so pervasive that Roman law began to crack down on magical practices. In particular, any form of magic that was believed to involve harm or manipulation of the gods was viewed as criminal. Magic wasn’t just seen as a moral issue—it was also a political one, as it threatened the stability of the Roman Empire by potentially giving undue power to individuals outside the traditional structures of authority.

The Role of the Lex Cornelia in Suppressing Maleficium

The Lex Cornelia, enacted in 81 B.C. under the dictator Sulla, played a key role in suppressing black magic and other harmful practices like poisoning. This law specifically targeted maleficium, classifying it as a form of criminal activity akin to murder and poisoning. By equating magic with serious offenses, the Roman state made it clear that maleficium was not just an immoral act but a punishable crime.

Under the Lex Cornelia, anyone caught practicing harmful magic or dealing with illicit spells faced severe penalties, including death. This legislation reflected the state’s need to maintain order by curbing the influence of black magic, which was seen as a growing threat to public safety.

The law also allowed for the confiscation and destruction of magical books, tools, and substances believed to be used in the casting of dangerous spells. This suppression was not just about eliminating magical practices, but also about maintaining control over any potential challenges to the Roman legal and religious systems.

Black Magic as a Crime: Public Perception and Punishment

The Roman public, deeply influenced by fear and superstition, saw black magic as a serious crime that could not only harm individuals but also destabilize society. The ability to control or destroy others through magical means was viewed as an unacceptable use of supernatural power. Romans believed that those who practiced black magic had crossed a dangerous line, using forbidden knowledge to interact with dark forces for personal gain or revenge.

Punishment for black magic was harsh. Those convicted of practicing harmful magic, particularly under the Lex Cornelia, could face execution or exile. These punishments were intended to send a strong message: magic that violated the laws of nature and the gods would not be tolerated.

In addition to legal penalties, public opinion also condemned practitioners of black magic, associating them with poisoners, criminals, and traitors. The fear of magic was so ingrained that even the suspicion of practicing harmful magic could lead to social ostracism or worse.

The Trial in Antioch: Magic as a Political Weapon

One of the most notable examples of the intersection between magic and politics in early Christianity was the trial in Antioch, which occurred between 371 and 372 A.D. under Emperor Valens. This trial began as a financial investigation into misused public funds but quickly escalated into a witch hunt for sorcery. The mere accusation of magic was enough to spark panic and lead to widespread executions, showing how deeply rooted the fear of magic had become in the late Roman Empire.

The trial resulted in the destruction of books believed to contain magical knowledge, many of which were actually texts on liberal arts and sciences. This incident illustrates how magic could be used as a political tool, with accusations of sorcery providing a convenient excuse to eliminate political rivals or dissidents.

For Christians, this trial demonstrated the power of magic as a weapon not only in the spiritual realm but also in the political arena, further blurring the lines between religion, magic, and state control.

Related reading: The Magicians of Mesopotamia: Who They Were and What They Did – Opens in new tab

The Role of Magic in Early Christianity

In the early years of Christianity, many of its rituals were misunderstood and even feared by the Roman authorities, who often categorized them as magic. Practices like the Eucharist, which involved the symbolic consumption of bread and wine as the body and blood of Christ, were seen as secretive and mystical, sparking rumors of cannibalism.

The early Christian community’s emphasis on resurrection, healing, and miraculous deeds further contributed to this confusion. To outsiders, these acts resembled the very same supernatural powers attributed to magicians.

The early Christian gatherings, which took place in private homes or hidden locations, also heightened suspicion. These clandestine meetings fueled the belief that Christians were engaging in dark, magical practices. As a result, Christian rituals were initially lumped together with the magic that the Romans associated with superstition and black arts.

Constantine’s Edict and the Legal Rise of Christianity

The turning point for Christianity came in 313 A.D. when Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, granting religious tolerance to Christians throughout the Roman Empire. This edict marked the beginning of Christianity’s legal recognition and its gradual rise to prominence. For Christians, this was a pivotal moment that transformed their religion from a persecuted faith to a state-supported one.

With this newfound legal status, Christianity began to separate itself more clearly from magic. What was once seen as a suspicious set of practices could now be practiced openly, without fear of persecution.

Supernatural Fears: How Christians Dealt with Pagan Magic

Even as Christianity gained legal recognition, fear of magic and the supernatural persisted. Pagan magical practices were still widely believed to be powerful and dangerous, posing a threat to the growing Christian community.

Ironically, the Church relied on the concept of magic to highlight the unique power of divine miracles. By acknowledging the existence of supernatural forces, the Church could make a clear distinction between magic and miracles. While magicians were depicted as using deceitful or evil powers, Christian saints were shown as channels of God’s will, capable of performing true miracles. This dichotomy allowed the Church to assert that divine power was far superior to any earthly magic.

The Church’s narratives about saints often involved them confronting magicians or performing miraculous acts that proved the futility of magic. These stories reinforced the belief that while magic could produce temporary results, it could never rival the permanent, righteous power of God. By using magic as a foil, the Church effectively elevated the sanctity of its own miracles, helping to strengthen the faith of believers and assert the authority of Christianity over pagan practices.

The Development of Anti-Magic Rhetoric in Christian Literature

Anti-magic rhetoric became a prominent theme in Christian literature, particularly in the writings of the Church Fathers. As Christianity gained influence, leaders like Augustine and Tertullian emphasized the sinful nature of magic, linking it to paganism and demonic forces. Magic was positioned as a perversion of the natural order, a tool used by the misguided and the wicked to disrupt God’s plan.

This rhetoric served not only as a theological stance but also as a cultural strategy. By vilifying magic, the Church distanced itself from practices associated with paganism and sought to establish clear boundaries between Christianity and the old belief systems.

Magic was not just wrong; it was dangerous, representing a form of rebellion against divine will. This narrative became embedded in Christian teachings, influencing everything from sermons to lawmaking, and contributed to the widespread fear and persecution of magicians during the medieval period.

Related reading: Magic in the Age of Enlightenment: How the Seventeenth Century Redefined Magic – Opens in new tab

The Miraculous vs. The Magical: Saints and Wizards

Apollonius of Tyana: The Christian Challenge of a Miracle Worker

Apollonius of Tyana was a significant figure that challenged the early Christian narrative. A philosopher and mystic from the 1st century AD, Apollonius performed acts that resembled the miracles of Jesus. He healed the sick, exorcised demons, and was even said to have raised the dead. To some, he embodied the ideal of a pagan holy man, with powers rivaling those of the saints.

For the early Christian Church, Apollonius posed a real challenge. His influence was strong, and many viewed him as a legitimate miracle worker. This led to comparisons between Apollonius and Jesus, forcing Christian writers to distinguish between the two. Apollonius’ powers were downplayed or explained as inferior to the divine miracles performed by Christ. This battle for spiritual authority was crucial as the Church sought to elevate Christian saints above any pagan rivals.

How Christian Saints Conquered Pagan Magic in Popular Culture

Christian saints gradually overtook pagan magicians in popular culture through their portrayal as protectors against evil. Stories and sermons emphasized how saints not only performed miracles but actively combated the harmful effects of magic. Saints were depicted as warriors in a supernatural battle, defeating demons and dismantling the power of magicians.

One effective method was the use of exempla—stories that demonstrated the saints’ ability to defeat magicians in direct contests. In these tales, magicians often performed incredible feats, but their powers were ultimately exposed as fraudulent or inferior.

The saints, by invoking God’s will, always triumphed, showing the superiority of Christian faith over pagan magic. These narratives became embedded in the cultural consciousness, reinforcing the idea that saints were the only true miracle workers, while magicians were deceitful and dangerous.

This strategy helped the Church in its broader mission to convert pagan populations. By positioning saints as the rightful wielders of supernatural power, Christianity offered a comforting alternative to the feared and misunderstood practices of magic. As these stories spread, they reinforced the idea that true miracles came from God, not from manipulative sorcery, cementing the role of saints as the ultimate spiritual authorities.

Related Reading: “Medieval Witch Trials in Europe”– Opens in new tab

The Controversial Simon Magus

Simon Magus was a mysterious and controversial figure from the early Christian era, often regarded as the epitome of a heretical sorcerer. His origins trace back to Samaria, where he gained a reputation as a powerful magician. Simon used his knowledge of magic to impress the local population, who believed him to possess divine power.

He wasn’t simply a magician, though; Simon also claimed to be a divine figure himself, even going so far as to say he was an embodiment of God’s power. This self-promotion elevated him to a dangerous level in the eyes of early Christians, making him a significant threat to the fledgling Church.

Simon’s Magical Abilities: Myth or Reality?

Simon Magus was said to possess extraordinary abilities that seemed to transcend the natural world. Some claimed he could fly, heal the sick, become invisible, and even manipulate objects with his mind. Accounts of his feats describe him as able to command supernatural forces at will, further blurring the lines between myth and reality.

However, the early Christian Church portrayed his powers as either fraudulent or demonic in origin. Simon’s abilities, according to Christian doctrine, were not the result of divine favor but rather dark forces or clever trickery. His magical prowess was a real concern for the Church, especially because his powers gave him a strong following among people who were easily impressed by such displays.

The Biblical Account of Simon and His Conflict with St. Peter

The conflict between Simon Magus and St. Peter is one of the most notable episodes in early Christian history. In the Acts of the Apostles, Simon is introduced as a figure who used magic to captivate the people of Samaria, convincing them of his greatness. However, after witnessing the miracles performed by the apostles, Simon was drawn to their power. He even underwent baptism, but his intentions were far from pure.

Simon’s attempt to purchase the power of the Holy Spirit from Peter—an act now known as “Simony”—was met with a harsh rebuke. St. Peter condemned Simon’s belief that spiritual gifts could be bought, exposing him as a fraud. This encounter marked the beginning of Simon’s downfall in Christian tradition, portraying him as someone who sought to commercialize divine power, an unforgivable sin in the early Church.

Simon’s Legacy: The Early Church’s Battle Against Heresy

Simon Magus became a symbol of heresy and false teachings, which the early Church fought to suppress. His attempts to blend elements of magic and Christianity were seen as dangerous distortions of the true faith. As the Christian Church grew in influence, so too did the need to distinguish between genuine doctrine and heretical practices.

Simon’s legacy as a heretic lived on through the writings of early Church fathers, such as Irenaeus and Justin Martyr.

They portrayed him not only as a dangerous magician but as a precursor to other heretical movements. His teachings, which sought to combine spiritual knowledge with personal gain, were held up as warnings of the kind of deviations that could lead believers astray. In this sense, Simon Magus was not just an individual but a representation of a broader challenge to Christian orthodoxy.

His story also highlights the early Christian struggle to define and control spiritual power. As Simon demonstrated, magic was seen as a form of power that could rival the miracles of saints. However, the Church worked diligently to discredit magic, framing it as a perversion of divine will. By doing so, the Church not only diminished Simon’s influence but also reinforced its own authority as the sole mediator of true spiritual power.

Related reading: Burning Words, Healing Bodies: How Medieval England Used Written Words to Heal – Opens in new tab

Final Thoughts

From its deep roots in Greco-Roman culture to its contentious relationship with early Christianity, magic played a significant role in shaping the beliefs and practices of ancient civilizations. It served as both a tool of empowerment and a source of fear, influencing everything from daily rituals to political power.

As Christianity emerged, the Church redefined magic, positioning it as a dangerous and deceptive force in contrast to divine miracles. This transformation not only marginalized magic but also solidified the Church’s spiritual authority.

Yet, magic never fully disappeared. Instead, it evolved, remaining a topic of both fascination and control. While its place in society shifted from reverence to suspicion, its enduring influence on belief systems persisted, embedded in the moral lessons, fears, and cultural narratives that guided the ancient world. In this complex dance between magic and faith, the legacy of magic continued to shape spiritual and cultural landscapes for centuries to come.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Source: “Ad omnia quae uelit incredibilis: An Overview of Ancient Magic from the Roman Context to its Late Antique Perspective and Models” by Nicola Mureddu

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Featured Image: The witches’ Sabbath, by Frans Francken II. Staatsgalerie Neuburg