Hypatia of Alexandria ( Greek: Ὑπατίᾱ η Αλεξανδρινή) was a female philosopher and an extraordinary woman not only for her time but for any time.

She was one of the last great thinkers of ancient Alexandria and one of the first women who study and teach mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy. Born in Alexandria, Egypt somewhere around 350 CE. Scholars long held that she was born in 370 CE but modern historians believe 350 CE to be more likely.

She was beautiful, brilliant, and bold. Greeks adored her! Even the men, who should have accused her of entering their field, admitted her outstanding achievements.

The Suda lexicon, a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, describes her as,

“exceedingly beautiful and fair of form. . . in speech articulate and logical, in her actions prudent and public-spirited, and the rest of the city gave her suitable welcome and accorded her special respect.”

Suda lexicon

She was the daughter of the mathematician Theon, who was the head and the last professor of a school called the “Museum” (Greek: Μουσεῖον) – the University of Alexandria.

Theon tutored her from an early age in math, astronomy, and the philosophy of the day which, in modern times, would be considered science. Nothing is known of her mother and there is little information about her life.

Hypatia’s Life

Hypatia never married and devoted herself to chastity, which possibly has been in line with Plato’s ideas. This made her far less threatening, because ancient Greek society prized celibacy as a virtue, and as such, men and women accepted and respected her.

Hypatia wore scholar or teacher clothing, rather than women’s clothes. She moved about freely, driving her own chariot, contrary to the rule of public behavior of women.

Beyond Theon’s areas of expertise, Hypatia found other means to learn about whatever interested her.

The great Library of Alexandria, which was part of the university (“Museum”), is said to have held 500,000 books on its shelves in the main building and more in an adjacent annex.

As a professor at the university, Hypatia would have had access to this resource and it seems clear she took full advantage of it.

She established herself as a philosopher in what is now known as the Neoplatonic school, a belief system in which everything emanates from the One.

Although this was something that only men could do at that time, Hypatia was not discouraged at all.

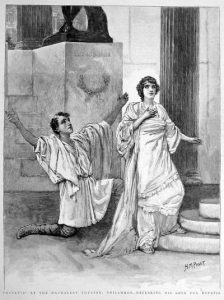

She used to speak into the center of the city and tell anyone who would listen, her thoughts about Plato. As a result, a lot of people were listening and were captivated by her interpretations and by Hypatia herself.

During that period, scholars didn’t publish original works but commented on classical mathematical works to develop their arguments.

Hypatia wrote her own commentaries and, collaborated with her father on some of his commentaries. It is thought that Book III of Theon’s version of Ptolemy’s Almagest was actually the work of Hypatia. She wrote in Greek, which was the language spoken by most educated people.

It has also been proposed that the closure of the ” Museum ” may have led Hypatia and her father to focus their efforts on preserving seminal mathematical books and making them accessible to their students.

She taught a succession of students from her home. Although she was a pagan, she was tolerant towards Christians and taught many Christian students, including Synesius, the future bishop of Ptolemais.

Letters from Synesius indicate that these lessons included how to design an astrolabe, a kind of portable astronomical calculator that would be used until the 19th century. Hypatia did not invent it, only designed it and constructed it (were in use long before she was born).

A Threat To Christianity

Hypatia was a paganism follower at a time when Christianity was in its infancy. The new religion began to grow and many pagans had converted to Christianity out of fear of persecution.

Alexandria was a great center of learning in the early days of Christianity but, as the faith grew in followers and power, steadily became divided by fighting among religious factions.

In that environment, Hypatia was a close friend of the pagan prefect Orestes and was blamed by Cyril, the Christian Archbishop of Alexandria, for keeping Orestes from accepting the new, ‘true faith’.

She was also seen as an obstacle to those who would have accepted the ‘truth’ of Christianity were it not for her charisma, charm, and excellence in making difficult mathematical and philosophical concepts understandable to her students. Concepts that contradicted the teachings of the relatively new church.

With Orestes in charge of the civil government and Cyril as the leader of the main religious body of the city, a fight began over who controlled Alexandria.

Orestes did not want to give up the power to the church. The struggle for power reached its peak following slaughter of Christians by Jewish extremists when Cyril led a crowd that expelled all Jews from the city and looted their homes and temples.

Orestes protested to the Roman government in Constantinople. When Orestes refused Cyril’s attempts at reconciliation, Cyril’s followers tried unsuccessfully to assassinate him.

Hypatia, however, was an easier target. She was a pagan who publicly spoke about Neoplatonism which was a non-Christian philosophy, and she was less likely to be protected by guards than Orestes. (Related reading: Paganism in Medieval Europe)

So, they spread a rumor, that she was preventing Orestes and Cyril from finding a peaceful solution to their differences. From this point, Peter the Lector and his mob took action and Hypatia met her tragic end.

This way Cyril had not succeeded at directly attacking the government, so he decided to eliminate one of its most powerful assets instead.

Check out our recommendations at “Philosophy Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Library“

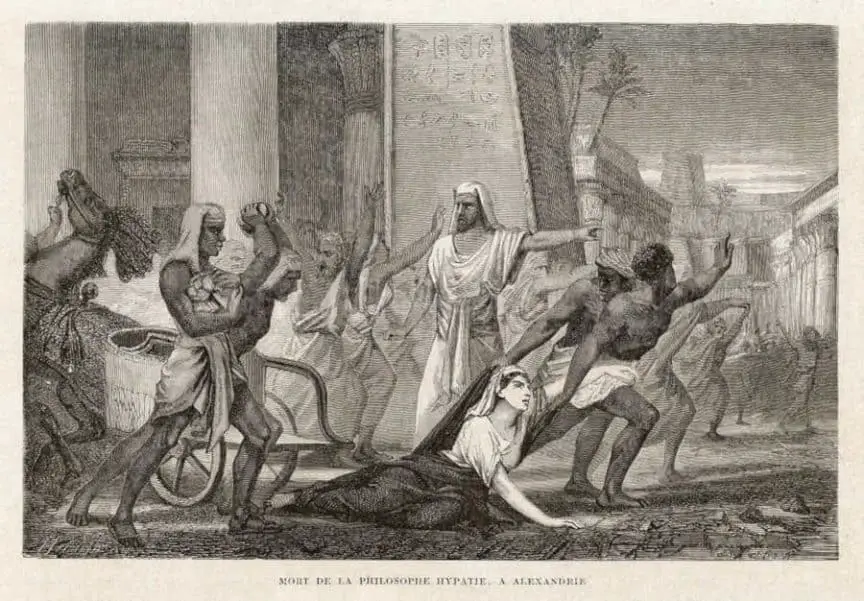

Hypatia’s assassination

Hypatia was murdered in 415 CE by a mob of Christian zealots (parabalani) led by Peter the Lector, who attacked her on the streets of Alexandria.

They dragged her from her chariot down the street into a nearby church known as the “Caesareum”, where they stripped her, scraped her skin off and beat her to death with roofing tiles.

They tore her body into pieces and dragged her mangled limbs through the town to a place called Cinarion, where they set them on fire.

This was according to the traditional way in which Alexandrians carried the bodies of the worst criminals outside the city limits to cremate them as a way of symbolically purifying the city.

Cyril justified their actions by saying that Hypatia represented idol-worship, which Christianity was opposed and fight against.

Later the church declared Cyril as a saint for his efforts in suppressing paganism and fighting for the true faith.

After Hypatia’s death the University of Alexandria was sacked and burned on orders from Cyril, pagan temples were torn down, and there was a mass exodus of intellectuals and artists from the newly-Christianized city of Alexandria.

Hypatia’s death has long been recognized as a turning point in history delineating the classical age of paganism from the age of Christianity. Thus, we can say that Hypatia was the last of classical philosophers.

Check out books about Hypatia – opens in new tab

Historical References to Hypatia

The primary sources, even those Christian writers who were hostile to her and claimed she was a witch, portray her as a woman who was widely known for her generosity, love of learning, and expertise in teaching in the subjects of Neo-Platonism, mathematics, science, and philosophy in general.

The Christian historian Socrates of Constantinople, in his Ecclesiastical History, describes her:

“There was a woman at Alexandria named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher Theon, who made such attainments in literature and science, as to far surpass all the philosophers of her own time.

Having succeeded to the school of Plato and Plotinus, she explained the principles of philosophy to her auditors, many of whom came from a distance to receive her instructions.

On account of the self-possession and ease of manner which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not infrequently appeared in public in the presence of the magistrates.

Neither did she feel abashed in going to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more.”

Socrates of Constantinople

Voltaire, in his “Examen important de Milord Bolingbroke” (1736) interpreted Hypatia as a believer in “the laws of rational Nature” and “the capacities of the human mind free of dogmas” and described her death as “a bestial murder perpetrated by Cyril’s tonsured hounds, with a fanatical gang at their heels”.

Later, in an entry for his “Dictionnaire philosophique” (1772), Voltaire again portrayed Hypatia as a freethinking deistic genius brutally murdered by ignorant and misunderstanding Christians.

Most of the entry ignores Hypatia herself altogether and instead deals with the controversy over whether or not Cyril was responsible for her death. Voltaire concludes with the snide remark that “When one strips beautiful women naked, it is not to massacre them.”

“Revered Hypatia, ornament of learning, stainless star of wise teaching, when I see thee and thy discourse I worship thee, looking on the starry house of the Virgin; for thy business is in heaven.”

Palladas, Greek Anthology (XI.400)

Nowadays people primarily remember Hypatia of Alexandria, as a martyr of female intellectuals and tragic heroine, for two things: her philosophical, mathematical, and astronomical teachings and the fact that she was brutally murdered for them.

Unfortunately for Cyril and his followers, by killing Hypatia, they immortalized her. Hypatia remains an inspiration, even in modern times.

Check out books about Hypatia – opens in new tab

Hypatia’s Quotes

“Reserve your right to think, for even to think wrongly is better than not to think at all. “

Hypatia

“He who influences the thought of his times influences all the times that follow. He has made his impression of eternity. “

Hypatia

“Fables should be taught as fables, myths as myths, and miracles as poetic fantasies. To teach superstitions as truths is a most terrible thing. The child mind accepts and believes them, and only through great pain and perhaps tragedy can he be in after years relieved of them. “

Hypatia

“Life is an unfoldment, and the further we travel the more truth we can comprehend. To understand the things that are at our door is the best preparation for understanding those that lie beyond.”

Hypatia

“Regardless of our Colour, Race, and Religion – We are Brothers “

Hypatia

“Truth does not change because it is, or is not, believed by a majority of the people.”

Hypatia

“To teach superstitions as truths is a most terrible thing.”

Hypatia

“All formal dogmatic religions are fallacious and must never be accepted by self-respecting persons as final. “

Hypatia

“To rule by fettering the mind through fear of punishment in another world is just as base as to use force.”

Hypatia

“Life is an unfoldment, and the further we travel the more truth we can comprehend. To understand the things that are at our door is the best preparation for understanding those that lie beyond. “

Hypatia

Further Reading: Check our Article “7 Female Greek Philosophers you Need to Know”

♦ If this article resonates with you, please join our newsletter by using the forms on this website so we can stay in touch.

Featured Image By Wikimedia Commons

Bibliography

- Novak, Ralph Martin, Jr. (2010), ‘Christianity and the Roman Empire: Background Texts‘, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 239–240, ISBN 1-56338-347-0(Aff. link)

- Watts, Edward J. (2017),’Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher‘, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780190659141 (Aff. link)

- Booth, Charlotte (2017), ‘Hypatia: Mathematician, Philosopher, Myth, London‘, England: Fonthill Media, ISBN 978-1-78155-546-0 (Aff. link)

- Deakin, M. A. B. (1992), “Hypatia of Alexandria”(PDF), History of Mathematics Section, Function, Melbourne, Australia: Monash University Mathematics Department, 16 (1): 17–22

- Deakin, Michael A. B. (1994), “Hypatia and her mathematics”, American Mathematical Monthly, 101 (3): 234–243, doi:10.2307/2975600, JSTOR 2975600, MR 1264003

- Dzielska, Maria (1996), ‘Hypatia of Alexandria‘ Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-43776-0 (Aff. link)

- Emmer, Michele (2012), ‘Imagine Math: Between Culture and Mathematics‘, New York City, New York: Springer, ISBN 9788847024274 (Aff. link)

Check out our recommendations at “Philosophy Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Library“