In the 15th Century, the crime of witchcraft could be prosecuted by both religious and secular courts of justice. When it was considered a heretic, and against the Sabbatical apostasy, it could fall under the Inquisitors’ jurisdiction, which happened on occasion.

But for the most part, witchcraft crimes, particularly when deemed to entail magical harm against people and their possessions, were judged by a secular court. These secular courts included the royal court, and the numerous autonomous courts presided by lords and city councils.

During the Medieval and Modern times, secular autonomous tribunals prosecuted more witchcraft crimes than the Inquisition, going against the common idea that many of the trials during the witch craze were initiated and presided by religious authority figures.

In truth, witchcraft crimes were often persecuted at the behest of the population, who often cited a context of rampant deaths and diseases. They would push the local authorities to arrest, prosecute, and punish those they deemed to be the perpetrators of evil deeds within their community.

That was the case in 1477 when a witch hunt was initiated in Mont-rós, a Catalan seigniory. According to the judicial records of Catalan’s Pyrenean area, the witch hunt begun at the request of neighbors and notable figures in the region, who addressed the governor as paraphrased below:

“The residents of Mont-rós are under extreme oppression from witches, and poisonous people, who we believe are behind the deaths and maiming of our children and cattle. We are aware that the problems stem from evil and poisonous people, for whom our region is famously known. To prevent further harm and destruction to our people and goods, and to remove these evil perpetrators from our society, we humbly request Your Mercies to intervene and see to the punishment of the criminals involved.” (Judical records from Montros -1477. Archivo Ducal Medinaceli, Fon Pallars, doc.510. Translated by Pau Castell)

Judicial records show that the governor accepted the claim and went on to arrest and prosecuted the alleged perpetrators via the local court of Mont-rós.

Another instance was recorded a few years later in yet another Pyrenean village. The account, as provided by a neighbor who was interrogated during the witch trial, stated that the villagers had approached the bailiff to take action against a suspected witch in their midst. The villagers complained that their livestock and possessions suffered due to evil forces.

The bailiff agreed to arrest the woman but warned the villagers that they would have to pay for the cost of trial if the woman was not guilty. What followed was the typical scenario that unfolded in witch hunts.

A public notary was sent out to take depositions from neighbors, and depending on the claims laid by the afflicted, the suspected witch would be arrested. Most of the witchcraft trials in Medieval and Modern Europe were initiated in this manner.

Related Reading: The Witch Stereotype and the Crime of Witchcraft – Opens in new tab

Sources tell us that in the majority of cases, persecution was initiated from the general population, who attributed the deaths of livestock and children, crop failures, and the spreading of illnesses to the actions and will of malignant people. It is the population that requested intervention from the authorities and inspired suspicion against some women for claims of participating in maleficent magic.

Such accusations would often devolve into obscure charges during the trials, and especially when torture was used to drive confessions out of the defendants. Under extreme duress, they would confess to making poisonous ointments meant to kill their neighbors’ cattle, participating in nocturnal rituals, abjuring God for the Devil, causing crop-destroying hailstorms, and even entering houses at night and crushing little babies to death.

There is a course titled “The Witch Trials” from the Center of Excellence. Click here to see details (Aff.link). You can use our code “LIGHTWARRIORSLEGION466 ” for 70% off.

These confessions are possibly a side effect of the mechanics of witchcraft trials in Medieval and Modern Europe. We must explore the entirety of the process, from the initiation of trial by public outcry to the ultimate sentencing and execution of punishment, to understand why the accused would confess to such misdeeds.

When a court agreed to initiate a judicial procedure, an inquiry would be subsequently launched to interrogate the neighbors of their suspicions. The inquirers would ask about the presence of witches in the area, the members suspected to be carrying out evil misdeeds, and any illnesses or deaths that happened under mysterious circumstances.

Known as the inquiries of voice and reputation (inquisitio de vox et fama), these first inquiries provided the court with a list of suspected witchcraft practitioners, most of whom were women. They were then arrested and brought before the tribunal for questioning.

Judicial Procedures for Witchcraft: The “Interlocutory Sentence of Torment” and Examination of Marks

The first interrogations were often met with resolute claims of innocence from the defendants. However, the courts considered the statements collected from witnesses during the inquiry to be incriminating evidence and could reinforce them using various judicial procedures.

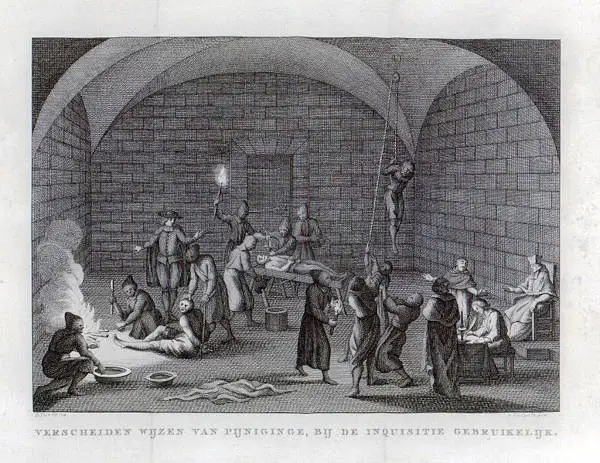

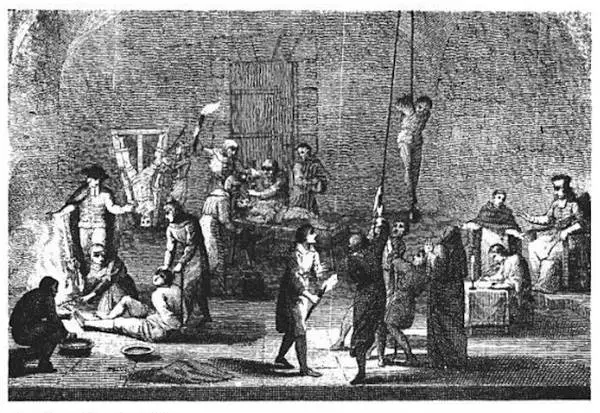

One of these procedures involved checking for physical marks on the defendants’ bodies, while the other involved torture.

Related Reading: “5 Amazing Witchcraft Cases that You Need to Know” – Opens in new tab

Examination of Marks

This test commonly followed the first inquiry process. It involved stripping the accused naked and checking for marks that indicated an association to the Devil and acts of malignancy.

Often, the marks would be found on the shoulders or back. Sometimes, they remained invisible until the skin was rubbed with holy water or pierced by a needle. Most of the time, the presence of a mark was not enough demonstration of guilt. Nevertheless, some tribunals considered marks to be enough evidence for a condemnatory sentence.

When the defendants innocence was still in question after this judicial procedure, the court would then proceed to the interlocutory sentence of torment (interlocutoria tormentorum ).

The Interlocutory Sentence of Torment

This part of the proceedings introduced torture into the interrogation of the accused. These torment sessions preluded a long series of confessions and admissions of guilt from the accused. As you can imagine, they were considered rather important to the judicial process.

Many torture methods tested endurance and pain tolerance as the accused would be hanged by her thumbs or with her hands tied behind her. Sometimes, they would add weights to their feet to increase the pain felt by the defendants.

One notable confession that arose from torment was recorded in 1471. Guillema Casala, a woman from the Pyrenean valley of Andorra, was accused alongside six other women for a series of deaths that had occurred in the valley.

Related Reading: “Church Versus Magic in The Early Middle Ages“ – Opens in new tab

Even after strongly refuting these accusations, the woman was eventually subjected to the interlocutory sentence of torment. She was hanged by her thumbs several times until finally, she confessed to the crime of witchcraft, citing another woman named Garreta as her initiator.

Her subsequent statement described in detail how Garreta convinced her to go to the “he-goat” (devil) through a ritual that involved the anointing of her armpits. She recounted that both she and Garreta eventually ascended a mountain where they met the Devil along with 20 cohorts who were dancing and eating fruit. Her account details her interaction with the Devil as well, describing how she kissed his hand and his buttocks before abjuring God and paying homage to the devil as her Lord.

She spoke of how she vowed before him to commit her evil deeds in secrecy while continuing to receive the Holy Communion. Her encounter ends with her carnal knowledge of the Devil, because of which she describes him as “having a very cold member.”

Confessions like these were very common in all the witchcraft trials across Medieval and Modern Europe. Rather than describing real encounters between the alleged perpetrators of evil and the Devil, they often bore the marks of scholars and readers’ interpretation of what the Devil would look and behave like.

This pattern of confessions was largely helped along by judicial torment. Consider that most of the accused evildoers were arrested on the grounds of performing maleficent magic and that any mention of the Devil arose only during the torment sessions, possibly coaxed out by the interrogators themselves.

Following these harrowing torment sessions, the accused would be left with little wiggle room to defend themselves. That’s because their confessions, despite being forced out by torture, were often taken as irrefutable proof of guilt and considered enough evidence to warrant the issuance of a death sentence.

Executions were usually carried out publicly, whereby the accused would be hung to death, then their corpses burnt. It could be said that these public executions greatly exacerbated the negative perception of witches as a threat to the public and were partially responsible for the ensuing witch craze that resulted in persecutions across Europe and beyond for centuries.

Related reading: Magic in the Age of Enlightenment: How the Seventeenth Century Redefined Magic – Opens in new tab

The Most Prevalent Accusations Against Witches

Many of the accused witches were purported to engage in infanticidal tendencies, that is, the mass murder of children. They would commonly be accused of visiting newborn children in the night and crushing them to death.

This was one of the most common accusations launched against suspected perpetrators of maleficent magic across Medieval and Modern Europe. An excellent example can be seen in the works of Johannes Nider, one of the first witch theorists ever recorded.

In his publication, the “Formicarius,” Nider recounts this heretical murder of infants in the words of a confessing witch. The witch starts by saying their attacks are leveled towards both baptized and unbaptized babies, especially those that are not “protected” by the sign of the cross.

The infants are murdered with the witches “ceremonies,” usually in their cribs or by the side of their sleeping parents, to make it seem like they were smothered to death.

After they’re buried, the witch recounts that they would dig up their infant bodies and boil them in a cauldron until their flesh falls off their bones and is soft enough to drink. The solid matter from this concoction, she finished, would be used to make ointments that they would use to accomplish their desires, make their evil arts, and facilitate their transformations.

Such confessions may appear to you as nothing more than the dark imaginings of clerics and religious fanatics, but they became deeply rooted in people’s mentality during this medieval period.

So great was the belief that women killed infants to fulfill their evil arts that many were suspected when their children died under mysterious circumstances.

A witness deposition made during one such trial shows where general opinions lay as far as the subject was concerned. The following account, recorded by a secular court in the Pyrenean valley of Andorra during the trial of Joana Call in 1472, was relayed by the defendant’s neighbor:

“On the night of Christmas day, I felt something crawl on top of me while I lay in bed. It was heavy as lead and constricted me so that I couldn’t move, and I believe it was looking for a child in the bed so that it could kill it. I managed to grab it and punch it before it could cause harm. I believe the entity was Joana.” - ANA, Tribunal de Corts, doc.1760, fol.1v. Translated by Pau Castell - (paraphrased)

This statement is almost identical to numerous other witness accounts issued during these witchcraft trials. In their accounts, there was always mention of strange sounds at night that preceded the deaths of children and cattle. They also pointed out that most of the child corpses had marks on them.

Related reading: Burning Words, Healing Bodies: How Medieval England Used Written Words to Heal – Opens in new tab

Another witness account from the same valley, this time during the trial of women of the Tomasa family, shows that the narrative remained the same throughout different accusations. The witness that gave the following account, as extracted from the court documents, was a woman that had recently lost her newborn child:

“She confirmed that she found her child unwrapped, crippled in the arm, and with the navel hanging out. When asked whether she had noticed any signs of abuse upon examining the corpse, she conceded, saying that the hand marks on the child’s corpse resembled a mark that she found on her breast. When asked whether she believed that human hands harmed the child, she conceded again, saying that the child’s blue sides and bruises indicated that the hands of a human being had crushed her. She suspected the perpetrator to be a woman from the Tomasa family.” - ANA, Tribunal de Corts, doc.5973, fol.2r-12r. Translated by Pau Castell - (paraphrased)

This was a strikingly common narrative pattern in witchcraft trials across Europe. It bore all the telltale signs of witchcraft based on the people’s knowledge of the maleficent actors. There was a dead child with marks on their body, suspicion against a neighbor, and the direct accusation of the defendants on trial in all accounts. Often, a series of child deaths would spur a witch hunt in the affected parish at the request of neighbors to the authorities.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Was Anyone Ever Acquitted After Being Accused of Witchcraft?

Some women were finally acquitted even after being accused of witchcraft and going through the lengthy and tortuous judicial process. The acquittal wasn’t very common, but there are four scenarios that usually ended with the release of the defendant and not their execution.

The first scenario was when the woman accused of witchcraft would confront her accusers and claim that they were merely after slander. If her counter-accusations were successful, then the charges would be dropped, and the accuser would be required to pay for the cost of the trial and sometimes an additional judiciary fine too.

The second scenario was when the authorities would launch an inquiry with the neighbors but fail to gather any substantial evidence against the alleged perpetrator of evil misdeeds. With a lack of evidence to go to trial, they would set the accused woman free after dismissing all the charges.

The third typical scenario was when the woman accused of witchcraft brought forth a trial defense of attorneys to refute the charges and invalidate the evidence. The attorneys would cross-examine the witnesses and their evidence and call their witnesses to the stand, giving the accused a fighting chance of getting justice.

This reveals that when the accused woman was allowed to have a defense, she was more likely to get acquitted of all charges. What’s more, if she could prove her innocence by getting through the interlocutory sentence of torment, the court would consider her above suspicion, but only after all the other evidence was invalidated.

Related Reading: “Medieval Persecution of Magic – The Inquisition and the inquisitor’s profile“– Opens in new tab

The fourth scenario involved appealing to a higher court. This could result in the complete acquittal of the accused because when a case was reviewed for another court, there was room to dismiss previously gathered evidence and even the defendant’s admissions made during the interrogation sessions. Although a last resort, it was the only hope for women who had already given what was considered a valid admission of guilt to their local, secular court.

This last scenario suggests that while some parts of Europe experienced numerous deaths following witch trials, some never did, all because there was room for appellation to higher courts in the land.

Specialists attribute this uneven intensity to the varying traditions across Europe, which led to some societies developing better judicial systems and more lenient local authorities than others. It is possible to conclude that the aggressiveness of the local authorities in hunting down and prosecuting witches played a significant role in the number of death sentences issued during the witch craze period.

Experts observed that in areas with centralized judicial systems were more likely to exercise control over the local courts and could even decide where specific cases would be held.

When this happened, the trial was held in a different territory than where the accusers lived; condemnatory sentences for practicing witchcraft were not only a few but nearly non-existent in some medieval and modern Europe areas.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Resources

- Course, Magic in the Middle Ages by Universitat De Barcelona from Coursera

- Cornell University Library: https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/witchcraftcoll/

- Medieval Sourcebook – Witchcraft Documents: https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/witches1.asp

- Inquisition records: https://www.york.ac.uk/res/doat/

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Featured image: Avvakum by Pyotr Yevgenyevich Myasoyedov