This article is separated into two parts for the reader’s convenience. In part one, we deal with the beliefs, origins, and history of Samhain; its connection to Halloween; similarities; and differences. In part two, we will look at how to celebrate Samhain (or Halloween) in traditional and modern ways and at its magical correspondences. Let’s start with part one.

As millions of children and adults celebrate Halloween on October 31, few will be aware of its ancient Celtic roots in the three-day Samhain (pronounced sow-win) festival, an old Celtic pagan celebration.

Samhain is also known as Autumn Cross-Quarter, Halloween, All Souls’ Night, Dark Moon, and Feast of the Dead, and it is sometimes referred to as Witches’ New Year.

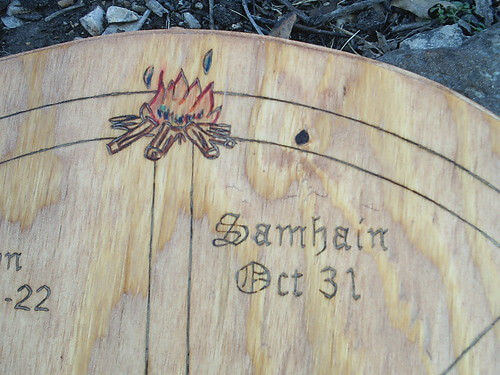

The ancient Celts split the year into two halves, the brighter half and the darker half, and celebrated the changing of the seasons with four festivals:

- Imbolc is a pagan holiday that happens halfway between the Winter Solstice and the Spring Equinox.

- Beltane is the midpoint between the spring equinox and the summer solstice.

- Lughnasadh occurs midway between the summer solstice and the autumn equinox.

- Samhain occurs midway between the autumn equinox and the winter solstice. (meaning literally “summer’s end” in modern Irish)

Samhain was arguably the most important of these four religious festivals since it is supposed to have symbolized the Celtic New Year.

On this day, particularly around dawn and dusk, the barrier between the visible world and the spirit realm is exceptionally thin. For the Celts, the day began not at dawn, but rather at dusk, with darkness. Light is always created from darkness; they are intertwined, interdependent, and necessary. Humans have celebrated Samhain as a time to remember the dead, tell fortunes, make plans for the next year, and rejoice in the successes and harvests of the previous year for generations.

Samhain is also one of the great festivals of the Wheel of the Year, and for many Pagans, it is the most important. It is the third and last harvest festival of nuts and berries, as well as a fire festival. Everything has been harvested; the cycle of birth and growth has come to an end, and now death is inevitable. The harvested seeds had dropped deep into the black earth, unnoticed, dormant, and hence seemingly lifeless.

The Goddess, now in the form of Crone, mourns the God until His return at Yule. The God, as Sun King, is sacrificed back to the land with the seed till the Winter Solstice. He journeys to the Underworld to absorb its wisdom. This is the phase of pre-conception, of the descend into darkness, from which new life and fresh ideas will finally emerge.

Samhain was also seen as a sacred period for gathering together and settling serious business problems. Debts were paid back, people who had done more serious crimes went to court, and justice was done as needed.

Samhain Origins and History

Samhain began as a “fire festival” in ancient Europe. The Celts lived 2,000 years ago, mostly in what is now Ireland, the United Kingdom, and northern France. On November 1, they celebrated the beginning of their new year. Of course, this was before the Roman Empire invaded and put an end to many of their paganism-based traditions.

Celts thought that during the night just before the new year, the barrier between the living and the dead was blurred. On the evening of October 31, they celebrated Samhain, believing that the spirits of the dead had returned to earth.

Celtic cultures had a superstitious fascination with times and locations that were “in between.” Sacred locations were any areas where land and water met (seas, lakes, and rivers), bridges, territorial boundaries (particularly when denoted by bodies of water), crossroads, thresholds, and so on.

These spots were haunted by ghosts, and the layout between neighboring properties was a place to avoid at all costs. Ghosts were also more likely to be encountered around bridges and crossroads. Naturally, burial sites were avoided on all nights, but especially on this one. There were ghosts of every kind to be seen here, and the dead freely mixed with the living.

Sacred times were also transitional points, with dusk and dawn denoting the shift between night and day, and Beltaine and Samhain denoting the change between summer and winter. Many myths and fairytales take place in such places and periods.

Samhain marked a transitional period between the two seasons, not just the passage from summer to winter. As a result, Samhain existed outside of time, belonging neither to summer nor winter. Samhain is also considered to have been a period of peace since the human realm was no longer limited by the laws of the physical world. With the spirit world so close, this was not the time for small fights between people.

Traditions and Beliefs

At the beginning of the Samhain festival, all fires were extinguished. The ancient Celtic priests, known as druids, would start a fresh bonfire and throw the animal sacrifices’ bones into it. This “bone-fire” is whence we get the word “bonfire” in current usage.

Since the purpose of the burning was to please the gods, they believed that expressing gratitude to the gods would encourage the gods to aid in the regrowth of their crops. After the celebration ended, they re-lit the fire in their homes from the sacred bonfire, in the hopes that the warmth and protection of the fire would carry them through the approaching winter.

Every year on Samhain, Donn, the Lord of the Dead, a divinity revered by the Celts, was thought to gather the souls of the dead from the previous year to begin their trip to the Celtic underworld, Tír na nÓg.

This was a time to contact the dead. They did this by lighting bonfires and lanterns to guide lonely or sad spirits home to see their family and by making what they called a “dumb supper,” which was an offering of food and vegetables.

The spirits of deceased ancestors might now be welcomed back into the home safely and without posing any harm to the household. On this night, the spirits of ancestors frequently sought comfort around the hearth. Fires were left burning in the grate to keep the spirits warm, and food was left for them. Despite the fact that the ancestral spirits were friendly, it was still a wise decision to avoid them by getting to bed early.

However, it’s possible that the spirits weren’t completely friendly. To appease them on this night, ritual offerings were necessary. The spirits were pleasant and kind as long as the offering was provided, but if the sacrifice was withheld, another side of the ghost’s features was shown. The home would be cursed, and things would not go well in the next year.

Some traces of this behavior may have remained in the present Halloween custom of “trick or treat.” Children disguised as ghosts and witches encourage residents to donate or deal with the consequences. The “treat” may reflect the ritual offering, but the “trick,” today a harmless joke, may have reflected the terrible repercussions of not pleasing the ancestral spirit on this night in antiquity.

Samhain was seen as a favorable time for druids to engage in divination since there was a stronger than normal link to the spirit realm. Because the barrier between the Otherworld and the real world was being lifted, the ancient Celts regarded Samhain as a dangerous time.

The Celtic Otherworld is frequently depicted as coexisting with, rather than being wholly different from, the human world. Remnants of this may still be observed today during Halloween, with the custom of coming to the church at midnight on Halloween and standing on the porch. If the brave watcher looks attentively, he will see the spirits of people who will die in the following year, but he risks meeting himself.

A parallel to this is that on this night, girls who look at themselves in the mirror will see a picture of their future husband, but they also face the chance of seeing the devil.

Those who are bold enough to go to a graveyard at midnight and walk around the graves three times will be able to see into the future, but they also risk meeting the devil. This latter example is noteworthy because it retains the three-time sunwise turn that the Celts used in the rite. Meeting the devil can be a reference to the well-known Christian attempt to equate the pagan deity of the dead with the devil of Christian doctrine.

As we already mentioned, Donn carried the souls of all those who had died in the previous year. The ceremonial offerings on the Winter Fires could have been an attempt to please him until he was supplanted by the devil with the introduction of Christianity at some point in history.

Samhain has nothing to do with evil.

Many people throughout history have believed that Samhain’s origins are dark and evil. This misunderstanding stems mostly from Charles Vallancey, a British military inspector and amateur historian who visited Ireland for the first time in 1762 while on a surveying trip.

Vallancey was so interested in the area that he wrote a three-volume book about its history and culture. However, the illiterate professor falsely asserted in his work that linguists had misinterpreted the term Samhain. Vallancey suggested that the word did not indicate “summer’s end” but rather related to a Celtic divinity called “Balsab” (bal meaning “lord” and “sab” meaning “death”).

Although scholars disregarded Vallancey’s assertions, his books continued to spread the notion that the Celts previously worshiped a satanic god, Lord Samhain, with burning human sacrifices and other savage ceremonies. Many early historians characterized the Celts as a savage race who performed ritualistic sacrifices on a regular basis, although it’s uncertain if these stories are true. Furthermore, neither of these narratives nor old Gaelic folklore particularly specified Samhain sacrifices.

Moreover

Early sources describe Samhain as a three-day, three-night event during which the community was obliged to appear before local monarchs or chieftains. People believed that if they didn’t participate, the gods would punish them with illness or death.

In Ireland, Samhain also had a military component, with festive thrones built for the leaders of soldiers. Anyone caught committing a crime or using a weapon during the celebration would be executed.

Some sources indicate six days of excessive alcohol consumption, usually of mead or beer, as well as gluttonous feasts.

From our current vantage point, the feast of Samhain is shrouded in mystery. We don’t know for sure, but historians believe the festivities featured animal sacrifices, dancing, and the wearing of costumes crafted from animal skins and maybe animal heads.

The Roman Empire had taken the majority of Celtic territory by 43 A.D. During their 400-year reign over the Celtic regions, two Roman festivals were mixed with the original Celtic festival of Samhain.

The first was a Roman holiday called Feralia, which was observed in late October and was dedicated to commemorating the dead. The second day was dedicated to Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruits and plants. The apple is Pomona’s emblem, and the inclusion of her festival into Samhain likely explains the Halloween custom of bobbing for apples.

Samhain Creatures

Offerings were placed for fairies, or Sidhs, outside of settlements and fields at Samhain because the Celts thought that the barrier between realms was breachable during this time.

It was anticipated that ancestors would also pass over during this period, and Celts would disguise themselves as animals and monsters to avoid being kidnapped by fairies.

Some creatures were associated with Samhain mythology, such as a shape-shifting entity known as a Pukah that gathers harvest offerings.The Lady Gwyn is a woman without a head who wears white and goes after people who wander around at night. She was followed by a black pig.

The Dullahan sometimes looked like mischievous creatures or men without heads who rode horses and carried their heads. Their appearance, riding flame-eyed horses, was a deadly omen to anybody who met them.

The Faery Host, a group of hunters, could also haunt Samhain and take people. The Sluagh, who came from the west to break into houses and steal souls, are similar.

Samhain and Christianity

As Christianity became the dominant religion in Europe, Samhain took on Christian labels and guises. The Western Catholic Church celebrates All Martyrs Day, which began when Pope Boniface IV dedicated the Pantheon in Rome on May 13, 609 A.D. to all Christian martyrs.

Later, Pope Gregory III enlarged the holiday to include all saints and martyrs, and he also moved the celebration from May 13 to November 1. All Saints’ Day soon included certain Samhain rituals. The previous evening was known as All Hallows Eve, and later as Halloween. Through time, Halloween grew into a day filled with activities such as trick-or-treating, carving jack-o-lanterns, celebratory parties, dressing up in costumes, and eating treats.

By the 9th century, Christianity’s influence had extended into Celtic territories, eventually blending with and supplanting ancient Celtic traditions. The church declared November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to commemorate the dead, in 1000 A.D. It is commonly assumed that the church attempted to replace the Celtic celebration of the dead with a comparable, church-sanctioned event.

All Souls’ Day was celebrated in the same way as Samhain was, with large bonfires, parades, and people dressed up as saints, angels, and demons. The festival of All Saints’ Day was also known as All-Hallows or All-Hallowmas, and the night before it, the customary night of Samhain in Celtic religion, became known as All-Hallows Eve and, finally, Halloween.

When Christian Spaniards came to Mexico, they mixed with the native ways of remembering the dead at this time of year. This is how Dia de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, came to be in early November.

Common Traditions with Ancient Origins

Trick-or-treating on Halloween in America is likely derived from early All Souls’ Day parades in England. During the celebrations, needy residents would beg for food, and families would offer them “soul cakes” in exchange for a commitment to pray for the family’s deceased relatives.

The church encouraged the giving out of soul cakes as a way to replace the old custom of leaving food and wine for wandering spirits. The tradition, known as “going a-souling,” was later adopted by youngsters who would visit their neighborhood households and be given food and money.

The Halloween costume custom has both European and Celtic origins. Winter was an unknown and dangerous period hundreds of years ago. Food supplies frequently ran low, and the short winter days were fraught with anxiety for many individuals who were scared of the dark.

On Halloween, when people thought ghosts came back to the real world, they thought they would see ghosts if they went outside. So, when leaving their houses after dark, individuals would wear masks to avoid being identified by these ghosts, fooling them into thinking they were other ghosts.

Furthermore, to keep spirits away from their homes, people would leave bowls of food at their doors to pacify the ghosts and prevent them from entering.

In the late 1800s, there was a movement in America to make Halloween a celebration of community and neighborly gatherings rather than ghosts, pranks, and witches. Adult and children’s Halloween parties have been the most popular ways to spend the holiday since the turn of the century. Parties were centered on games, seasonal delicacies, and spectacular costumes.

Trick-or-treating, which dates back hundreds of years, was also revived between 1920 and 1950. Trick-or-treating was a low-cost way for an entire town to participate in the Halloween festivities. Theoretically, by giving the neighborhood kids little goodies, families may also stop pranks from being played on them.

As a result, a new American custom was formed, and it has since grown. Today, Haloween is the second largest commercial holiday after Christmas in the U.S.

Samhain and Wicca

With the rise of Wicca in the 1980s, Samhain in its old pagan form came back to life in a big way. Wicca celebrates Samhain in many different ways, such as with traditional fire rites, festivals that are similar to modern Halloween, and activities that have to do with nature or the dead.

Wiccans regard Samhain as the end of the year and incorporate typical Wiccan practices into the celebration. Near Samhain, American Pagans often have parties called “Witches’ Balls” with music and dancing.

Related Reading: The 8 Major Annual Wiccan Holidays (Sabbats) – Opens in new tab

Reconstruction of Celtic Culture

Celtic Reconstructionists are pagans who accept Celtic traditions in order to accurately restore them in modern paganism.

In this culture, Samhain is known as Oiche Shamnhna, and it commemorates the union of the Tuatha de Danaan gods Dagda and River Unis. Celtic Reconstructionists decorate their homes with juniper branches and host a feast in memory of ancestors at an altar dedicated to the dead.

The Samhain Fire Festival and the Hill of Ward

The Samhain fire festival was held in Ireland by the ancient Celts at the Hill of Ward, also known as Tlachtga, named after a strong druidess who passed away there after giving birth to triplets. The Hill of Ward is located in the Boyne Valley in County Meath, Ireland, about twelve miles from the Hill of Tara.

Compared to its more well-known neighbors, including Newgrange, The Hill of Ward has gotten less attention. In the 1930s CE, archeological research was undertaken on the site, but it was not revisited until 2014 CE, when excavations directed by Dr. Stephen Davis of University College Dublin began. The study revealed that the Hill of Ward was likely built in three periods, the first dating back to the Late Bronze Age around 1200 BCE and the most recent going back to the early medieval era around 400 CE.

Archaeologists discovered evidence of large-scale burning at the site, as well as remnants of burned animal bones. Some of the nearby ancient ruins are even older and provide evidence of pagan traditions in Ireland that predate the advent of the Celts some 2,500 years ago.

For instance, the age of Newgrange and the Mound of the Hostages is around 5,000 years. Similar to how the passage at Newgrange is aligned with the daybreak of the winter solstice, when its inner chamber and passageway are lighted, the Mound of the Hostages is aligned with the sunrise around Samhain, indicating that this particular time of year has played a significant role in ancient Irish spirituality for at least 5,000 years.

Samhain – Halloween: Similarities and Differences

Halloween and Samhain share similarities in timing and content, yet they are distinct celebrations. Halloween is a secular traditional holiday in modern America and internationally. People from various walks of life, cultures, and beliefs come together to enjoy this holiday, just like they do for Thanksgiving. Also, Halloween has become a holiday for families with young children as well as a time for people of all ages to dress up, go trick-or-treating, tell stories, act out scenes, play jokes, visit scary houses, and have parties.

Samhain, on the other hand, continues to have a religious orientation and is celebrated spiritually by its devotees, as are its corresponding Christian holidays. The core Samhain ritual of honoring the dead is a serious religious practice and not a playful pretended dramatization, even if celebrations may involve merriment.

Even though they are somber and focused on death, modern Pagan Samhain celebrations do not include the sacrifice of humans or animals. Another distinction between Samhain and Halloween is that the majority of Samhain rituals are performed privately rather than publicly.

Halloween began to emerge

Because of the strict Protestant belief systems in colonial New England, Halloween celebrations were highly limited. In the southern colonies, such as Maryland, Halloween was considerably more prevalent.

As the beliefs and rituals of various European ethnic groups and American Indians merged, a uniquely American form of Halloween emerged. The earliest festivities were “play parties,” which were public activities intended to celebrate the harvest. Neighbors would tell ghost stories, tell fortunes, dance and sing.

During Colonial Halloween celebrations, ghost stories were told and all kinds of mischief were made. By the middle of the 1800s, many places had annual fall celebrations, but not all of the country had yet adopted Halloween.

Due to the famine in Ireland in the 19th century, many Irish people were forced to move to America. They brought with them traditions and beliefs that are still practiced on Halloween, such as carving jack-o’-lanterns.

The “Stingy Jack” legend originated in Ireland and Scotland and was about a man who tricked the devil. Because of his dubious actions, he was denied entry into either paradise or hell upon his death. He was given nothing more than a bit of coal by the devil to light his path. Jack made a sort of lantern out of the burning coal by putting it in a carved-out turnip. He has been walking around the world with his lantern ever since.

So, the tradition of carving scary faces into turnips and potatoes to make jack-o’-lanterns started as a way to scare away Stingy Jack and other evil spirits at Samhain, when the worlds of the living and the dead meet.

When Irish people moved to America, they brought the tradition with them. Over time, the tradition changed to using pumpkins, which grew easily in America.

Trick-or-treating evolved from the ancient tradition of mumming in the evenings preceding Samhain. Mummers would dress up and sing songs for the dead as they went door to door in Ireland. In exchange, Samhain cakes were provided, and pranks were committed and blamed on fairies.

It seems like people wore costumes for two different reasons. One of the reasons was to hide from malevolent spirits. Another was to pretend to be such spirits and take donations while gathering food for Samhain feasts.

Now take the related Quiz, to check your knowledge of Samhain and Halloween!

Continue reading the second part of this article: How to Celebrate Samhain (or Halloween) – Traditions and Symbols

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Featured Image by Pexels from Pixabay