According to Jonathan Barry, an acclaimed British historian, few other historical subjects have drawn the attention of historians and fanatics over the years as witchcraft has. This is no surprise as, over the last 200 years, many historians have dedicated their life’s work to studying the history of witchcraft.

As a result, today, there exists mountains of historiographical literature on the subject. This article will provide a dissecting view of some of their most popular conclusions to offer an in-depth understanding of the rise of the witch craze during the late Middle Ages.

When did witchcraft become a crime?

During the last centuries of medieval times, a new crime came to being across Europe. The crime was defined by rumors of diabolical assemblies, pacts with the devil, apostasy, and illness and death caused through various superstitious means.

The men and women accused of committing the new crime were labeled bruxas, sorcerers, Hexen, and witches. The distinctive naming is in line with the different traditions and cultures spread across the continent at the time.

According to contemporary sources, the names referred to maleficent magic and anti-heretical tradition. In some cultures, they were associated with mythical creatures believed to carry out gruesome nightly attacks.

The preachers of the time were like fuel to a burning fire. They preached the dangers of the magical practices while creating a link between the diabolical diviners and sorcerers and the misfortunes that would befall a haunted society.

Vincent Ferrer was one of the most popular anti-witchcraft preachers of the early 15th century. In 1416, while preaching across Southern France, he came to a village known as Clermont-Ferrand. Here he said;

“That we must come to the Christ and not the sorcerers, who cannot give you anything but hell. And expel the sorcerers because to sustain them is terrible to God. And for this end, do not save the firewood, for once the truth is known, they should be burned ...”

The words are as cold as they sound, and they became the primary message of preachers across the continent. A few years later, witch trials became a common occurrence in various parts of Europe. This would be the beginning of what would be the great persecution of persons accused of witchcraft. The alleged crime, which was seen as a heinous act against God and society, led to thousands of people getting burned on the stake.

Related Reading: “Church Versus Magic in The Early Middle Ages“ – Opens in new tab

Maleficent Magic – The “witch stereotype” of the 14th and 15th centuries

The “witch stereotype” become widespread in the 14th century, though it was already a matter of concern in some medieval European societies much earlier. The Vincent Ferrer speech in the early 15th century marked a tipping point for widespread persecution of alleged witches in the continent. The “witch stereotype” has strong ties to maleficent magic, a central belief in many societies.

The concept of maleficent magic outlines that there are people in any society who are set to cause harm to others or society through magic. It’s derived from the medieval term “Malefecia,” which was used to explain the practice along with “Veneficia,” which is an expression for poisoning.

During the onset of the “witch stereotype,” secular laws were put in place in some societies to draw a clear distinction between beneficial magic and evil practices. The earliest example of such a law is from the 12th century and was promulgated by King Alfonso the Wise of Castille.

Part of the law states: “Every person of the village can accuse soothsayers, sorcerers, and other impostors, of whom we talk about in this chapter, in front of a judge. And if witnesses prove that they have done some evil deeds, they must die for that. But for those who perform enchantments or other things with good intention ..., they must not be harmed, and they should receive a price for it.”

Though this law draws a distinct line between malicious magic and good magic, the line was not as clear to the ecclesiastical elites. They choose to condemn magic in its entirety as it posed the threat of leading people away from the one true God.

Despite this, people’s minds became used to the idea of good and bad magic over time. A considerable number of medieval European societies would adopt similar laws, and they would widely be used in the maleficent magic trials.

The wide adoption of the law also birthed some peculiar instances of how the accused witches were required to prove their innocence and absolve themselves of practicing dark magic. Such was the case in the Pyrenean Valley of Aneu during the 14th century.

Here, the defendants had to undergo the ordeal of iron to prove their innocence. The ordeal involved the defendant holding a hot iron rod, and the healing of their wounds was observed. If the defendant had a quick recovery, they were innocent. Contrary, a slow recovery indicated guilt, and the defendant was executed by fire.

As the years passed, both good and bad magic became distasteful to the majority of medieval European societies, and the “witch stereotype” a darker reality.

Related Reading: “Medieval Witch Trials in Europe”– Opens in new tab

From the Individual Witch to the Maleficent Group of People

A close examination of various theological works and sermons of the preachers of the time shows the evolution of witchcraft from an individual practice to one undertaken by a maleficent group of people. The people who perform magical activities are progressively painted as a sect of maleficent individuals out to pollute Christian society through their ungodly acts.

This school of thought became more mainstream in the 15th century. Many mendicant preachers like Vincent Ferrer and Bernardino de Siena discussed maleficent sects whose members assembled at night to perform dark rituals in their sermons. They alleged that some of these rituals were directed at provoking illness and death.

The popularity of the thought of people who perform magic as a sect of evildoers led Pope Alexander V to condemn them in 1409. The situation became even direr soon after as people started to relate the evils and misfortunes that befell their societies to the misdeeds of such sects.

The evolution spread across Europe and reached the Pyrenean valleys, which was infamous for its ordeal of iron witch trials. In 1424, the first instance of an alleged witch being subjected to the ordeal of iron for being part of a maleficent magic sect was recorded.

The defendant, who was a woman, was accused of being part of a group of persons that assembled at night to pay homage to the devil and abjure the Christian faith. It was also alleged that the sect kidnapped babies and killed them as part of their sorcery.

At the time, diabolism coupled with heresy and maleficent magic was what was termed as the crime of witchcraft.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

The Medieval Figure of the Witch and its Mythological Component

The “witch stereotype,” which became prevalent at the end of the Middle Ages, also had a solid mythological component. Richard Kieckhefer, a scholar who has specialized in the history of witchcraft, points out that the earliest mythologies of witchcraft came up during the 15th century.

Richard said that while studying the history of witchcraft, he realized that some records of trials and treaties on witchcraft from early in the century had some curious magical elements. Some of these curious elements included mythical night figures with bizarre abilities like entering closed houses, changing shape, and flight. The most peculiar of the mythical night figures had infanticidal tendencies.

The mythical witch figures of the 15th century borrowed heavily from the ancient myths of different cultures like the Greek and Roman period and some much older ones. Among the most relatable ancient myths is that of “Strigae,” the bird-women who used formulas and ointments to transform themselves and enter houses at night to suck children’s blood.

Another famous ancient myth that inspired the mythical component of witchcraft is the “Lamie,” which specialized in abducting babies from their homes at night, dismembering them, and eating them.

The Nightmare was another ancient mythical creature common across various ancient European cultures and went by different names. The creature is said to enter houses at night to crush and suffocate its occupants, sometimes resulting in death.

Related reading: Magic in the Age of Enlightenment: How the Seventeenth Century Redefined Magic – Opens in new tab

Before witchcraft became a thing in Europe, these ancient mythical creatures were part and parcel of everyday beliefs. It was a tradition for mothers to perform various rituals to protect their children from these nocturnal creatures.

The most common ritual was setting the table with food, drinks, and a mirror before going to bed. These would act as enough distraction to the ancient mythical creatures if they broke into a house at night, thus saving the children. In addition to this, the mothers would have their children wear coral necklaces for protection. Others would enlist the help of sorcerers to protect their babies with charms and incantations.

When the age of witchcraft set in, the ecclesiastical authorities were quick to dismiss the ancient nocturnal figures as demons and evil spirits. Their purpose was said to be misleading people away from true faith through superstition.

It didn’t take long from this point for the ecclesiastical authorities to connect the ancient superstitions with real people accused of maleficent magic. The association came when these authorities began to worry about the powers of the devil and how they manifest in the human world physically. The clerics started opening up to the idea the ancient mythical creatures might be real and corporeal beings that can act in the physical world.

As a result, the individuals who believed in mythical creatures and claimed they could interact with them were seen with suspicion. They also received the blame for all the misdeeds believed to have been caused by the creatures at night.

Related Reading: Magic in Islam During Middle Ages – Opens in new tab

In the 1380s, one of the earliest examples of such suspicion and blame against those believed to be interacting with the ancient mythical creatures was recorded in Italy. Two women, Pierina and Sibilla from Milan, were arraigned before the bishop’s court repeatedly on charges of magical activities and superstition.

The women later confessed to being part of a female fairy society that met at night. The society was called “il gioco” (the game), and their night meetings were presided by a female figure and involved singing, drinking, before entering houses. The women claimed that they had also received blessings from the lady leader of the fairy society.

Unsurprisingly, their story bears a strong resemblance to the traditional mythology of “the good ladies” or “Dominae Nocturnae,” “Bonae Dominae,” “Bonae Res,” and “Dominae Albae” in different European cultures of the time. The mythology of “the good ladies” involved households tidying their houses and leaving food and drinks for the fairy ladies at night. This would please the fairy ladies and attract good fortune to the household if they visited.

Despite the seemingly harmless nature of “the good ladies,” things took a turn for the worst for Pierina and Sibilla during their repeated trials after the Inquisitors of Milan intervened. They pressured the women to confess to paying homage to the female figure leader of the fairy ladies sect. It was said that it was forbidden to mention the name of God in the presence of the fairy ladies’ sect leader.

Pierina and Sibilla also confessed to have invoked Lucifelum, an evil spirit that transported them to the game, and they engaged in sexual intercourse with it. They added that they had made a blood pact of fidelity with the bad spirit. As bizarre as their confession may sound now, it sealed their fate. The two women were condemned as heretics, and in 1390, they were burned on a stake in Milan.

Related reading: Magic in the Age of Enlightenment: How the Seventeenth Century Redefined Magic – Opens in new tab

In 1419, another mind-blowing case was recorded in the Catalan city of Barcelona, not far away from Milan. Here, another woman was presented to the bishop’s court for engaging in magical activities relating to fertility and children’s protection rituals.

During the trial, the woman claimed to have the ability to protect infants from attacks by bad spirits like witches and ghosts. Her method was the age-old tried and tested – setting the table with food, drinks, and a mirror. During the questioning, the woman was asked if she knew any witches or individuals in league with them within the city. Unfortunately, neither her response nor her fate was recorded.

It wasn’t long after this that in the Pyrenean valleys, which is north of Barcelona, women started getting burned on the stake on allegations of witchcraft. Their crimes ranged from drinking and feasting with demons, abjuring the Christian faith, to abducting and killing children.

The Witch Stereotype in Medieval Sources

Ambrosius de Vignate offers some of the most vivid accounts of the witch stereotype among medieval sources. He lived in 15th-century Italy and was a celebrated legal scholar and magistrate, who also lectured at the Torino, Bologna, and Padua universities.

As a magistrate, he had the unique opportunity of taking center stage at several trials involving alleged witches. This enabled him to have exclusive insights into the confessions of both women and men accused of witchcraft, some of who spoke freely and others who were tortured. They confessed to belonging to a maleficent magic sect and to doing all kinds of awful things.

According to Ambrosius, the witch stereotype in the late medieval times was based on a combination of demonolatry heresy, mythological motives, and maleficent magic. Though all of the individual elements existed on their own before, it was their combination in a coherent way that made the witch stereotype stand out.

Admittedly, not everyone believed what the defendants in the witch trials confessed. The legal scholar points out that many people were openly skeptical about the reality of what the alleged witches said. Despite this, the witch stereotype had gotten life, and it quickly spread.

There is a course titled “The Witch Trials” from the Center of Excellence. Click here to see details (Aff.link). You can use our code “LIGHTWARRIORSLEGION466 ” for 70% off.

Another great insight into the witch stereotype at the end of the Middle Ages is by Petrus Mamoris, a French scholar in his 1460 book “Flagellum Maleficorum.” At the time, he was a regent at the University of Poitiers, and he was covering the subject of witchcraft under the direction of the Bishop of Saintes. Petrus’s account of the witch stereotype is quite similar to that of Ambrosius.

Firstly, both are based on a combination of various superstitions and traditional elements. Additionally, both “witch theorists” talk about women covering great distances at night and entering locked houses. Their accounts seem to be like those of “Strigae” and “Lamiae.” The Frenchman’s theory is even more striking; he talks about the women roaming the night, ripping the children from their mothers’ arms.

Additionally, both accounts involve wine pillaging, just like it’s told in the ancient mythologies of “the good ladies.” The “witch theorists” both have their accounts take a demonological turn when they introduce the argument of the women flying in the company of a demon. When they get to the demon’s chambers, they feast and engage in sexual intercourse, praising the dark lord and abjuring God.

The similarities in the accounts of Ambrosius de Vignate and Petrus Mamoris are a clear indication the witch stereotype across Europe at the time was similar. It’s no surprise that most of the alleged witches in the continent met the same fate – burning on the stake.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Resources

- Course, Magic in the Middle Ages by Universitat De Barcelona from Coursera

- Cornell University Library: https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/witchcraftcoll/

- Medieval Sourcebook – Witchcraft Documents: https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/witches1.asp

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

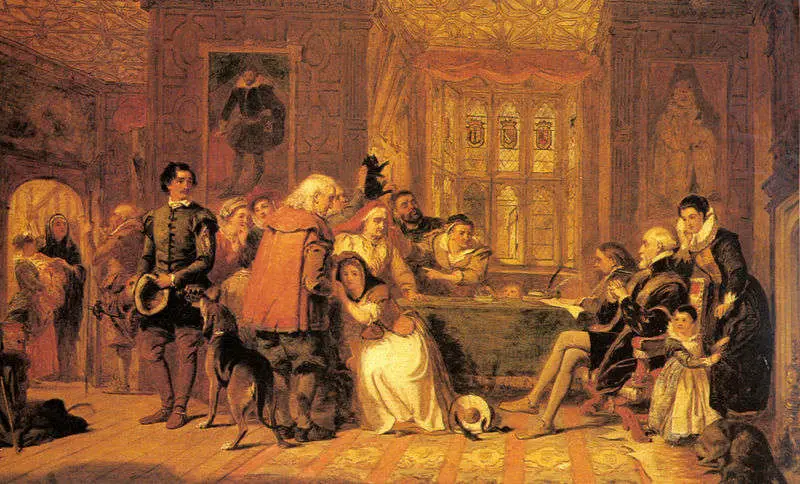

Featured Image William Powell Frith The Witch Trial