Magic of the demonic and natural sort alike has been a favorite subject of Christian authors of earlier times onto the medieval theologians that came after them. Those who practiced magic would gradually fall under the harsh spotlight of what we now commonly understand as religious persecution.

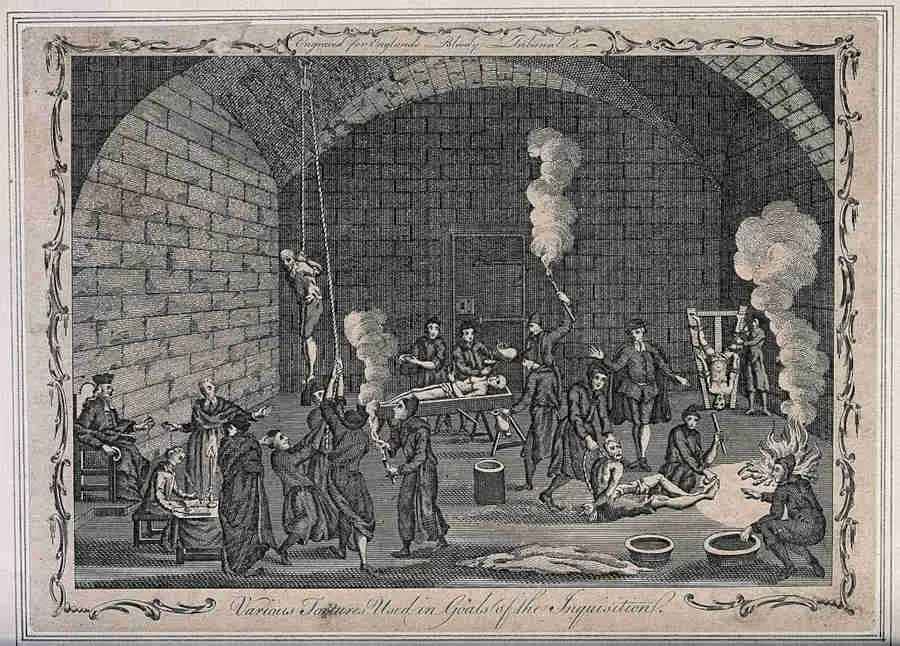

In the 13th century era, a new phenomenon came to bear on the proceedings, and it would begin to bring forth results as nothing else before had done. This was to be the era of the inquisitorial tribunals.

Most people consider the decade bearing the 1230s, or the Middle Ages, to be the foundational timeframe for ‘the inquisition,’ but this is somewhat erroneous. In truth, as most of us have come to understand it, the inquisition came into existence as a solid institution well beyond this era.

What was taking place from the 13th century on to the end of what we consider the Middle Ages was an essentially different exercise. It would be more truthful or accurate to speak of the activities occurring within these years as the efforts of appointed individuals as they took to their tasks exceedingly conscientiously. We refer to them as ‘inquisitors.’

These men were sampled from the clergy, and their objective was to persecute heretics. When we speak of heretics, it’s important to note that these were only those of the Christian faith who strayed from the path defined by the divinely authoritative Pope, bishops, and infallible dogma. The essential point here is that Jews, Muslims, and any who did not proscribe to the faith fell out of the inquisitors’ jurisdiction.

To fulfill their sacred (according to the faith) duties, inquisitors were privileged with certain powers. Papal authority (derived from the Pope) allowed them to act upon any evidence that they considered credible. This ‘ex officio’ status meant that they could act upon evidence as flimsy as rumors, children’s accounts, convict statements, or even the sayings of madmen—the weighing of the evidence against the accused lay entirely upon them.

Accused persons were encouraged to incriminate themselves and sell out their brethren as the process of inquisition carried on in secret. It was a seemingly inexorable machine that would snare as many heretics as possible, and just like any wide-enough net, it would inevitably catch many unintended preys.

Persecution of Magic in Medieval Times

Up to this point in many people’s understanding, the persecution of those deemed practitioners of magic is baffling. They wonder – what prompted those tasked with heretics to turn their attention to magic practitioners (otherwise referred to as sorcerers) in those times?

The answer lies in Christian doctrine and practice. The baptismal ritual involves the rebuking or renouncing of Satan and all his minions. Falling back into his clutches, or ‘relapsing,’ translated to a dire abjuration of the Christian faith. Inquisitors were tasked with effecting the scripturally just punishment for such aberrations – death by fire at the stake.

The head of the Church at the time was, however, mindful of the reality that this sort of fatal authority might be subject to misuse or injustice. Pope Alexander the Fourth decreed that in cases where a clear link between magic and heresy could not be found, the case was to be left in the hands of the local authorities concerned.

Early in the 14th century, Pope John the 22nd overturned this decree. His decision was based on the argument by many inquisitors that all magic had a heretic implication as it carried demonic elements and applied just as well to an individual’s actions as it did to their beliefs. The Pope thus allowed for the persecution of magic practitioners, necromancers, and sorcerers in general.

Profile of an Inquisitor: Their Nature and Objectives

Most people have a very dark opinion when it comes to the subject of medieval inquisitors. We view them as exceedingly sadistic, hardheaded torturers who indulged in their obscene proclivities in the name of the Church.

That’s not the whole picture by any means. Medieval inquisitors were, by and large, believers of the Church who would be the first to advocate against any torture. Their overriding objective was to identify and expose any threat to the Christian faith and see to its elimination. The fiery stake was their final resort, with careful and conscientious deliberations preceding each sentencing.

This went against the prevalent practice of the times they lived in, where mob persecutions were the norm. Lynchings without any semblance of procedure, deliberation, or effort at justice were regular occurrences. While being brought under the glare of an inquisitor was by no means a desirable situation, suspected sorcerers were afforded certain protections or guarantees that more spontaneous mass actions certainly did not.

Documented cases exist challenging this assertion, such as those where the very Devil was invoked in the official proceedings. The trial of Joan of Arc and the persecution of the Knights Templar present themselves as prominent examples of this. They faced charges that included, among other things, the veneration or worship of a cat and goat’s head. However, such proceedings were strongly tinged by the political machinations of the time, more so than any religious zealotry.

The Satan of the Bible was invoked as a readily credible scapegoat in many instances. While the accounts of orgies, child sacrifice, incest, blood baths, sodomy, and summoning rituals prevalent in these proceedings were sensational enough, they were nothing new. Ironically enough, these exact charges had been applied in previous eras to what had been labeled a dangerous heretic sect but would eventually come to change the spiritual countenance of the world, namely: Christianity.

There is a course titled “The Witch Trials” from the Center of Excellence. Click here to see details (Aff.link). You can use our code “LIGHTWARRIORSLEGION466 ” for 70% off.

Bernard Gui: Detailing the Inquisitor’s Guidebook

We know most inquisitors not only thanks to the places they earned for themselves in the history books, but to the books and documents that they left behind for posterity. Prominent figures in this much-maligned roster include Jacques Fournier (later became Pope Benedict the 12th), Nicolas Eymerich (went on to be Inquisitor General of the Aragon Crown), or the infamous Thomas of Torquemada. The last has grown to be the ostensible poster boy for inquisitorial excesses in his role as the Grand Inquisitor of the Holy Office late in the 15th century.

The novel titled ‘The Name of the Rose,’(Aff.link) penned by one Umberto Eco, and the movie based upon its prose, played a significant role in popularizing the image of sadistic inquisitors towards the end years of the 20th century. This image persists to this day. In the book, Bernardo Gui is depicted as an evil Dominican inquisitor instrumental in the torture and eventual execution of a duo of falsely accused monks and a girl accused of witchcraft.

These charges, shown to be objectively false in the book, are depicted as being the machinations of the power-mad Bernardo as he uses the overwhelming powers of the Church to see through his vendettas and prejudices on an innocent populace.

Is this a factual recount of events? Not really. While the fact stands that one Bernardo Gui was an inquisitor of the Dominican order, almost everything else can be attributed to the author’s artistic license and sensationalist tendencies. It makes for a dramatic read and an exhilarating viewing experience, but the facts tell an entirely different story.

It is, perhaps, appropriate to make a disclaimer of some sort here. My objective is not to defend or extoll any actions instigated or carried out by these characters. The goal is to increase our understanding of their motives and reasoning to place their actions in their proper historical, moral, and institutional contexts. As objective researchers delving into this historical matter of interest, it shouldn’t, and doesn’t, matter how abhorrent their actions might seem to us peering back in time.

That aside, Bernardo Gui as an actor in this historical drama, was undoubtedly a real personage, deeply involved in the struggle against what to him and many of his peers were actual and imminent threats to the late medieval Church.

Related Reading: “Church Versus Magic in The Early Middle Ages“ – Opens in new tab

Born in the year 1261, he was inducted into the Dominican Order at the not so tender age, by those era’s standards, of 20 years. He rose to the rank of Inquisitor for the Toulouse region in 1307 and held that position for approximately 18 years. Within those years, 600 people were brought under trial by him, and 40 men and women (around 7%) subsequently met their deaths at the fiery stakes. His death was a peaceful one at his bed in the year 1331, aged 70.

His significance for our purposes, however, is what he left behind. Bernardo Gui wrote copiously, but his most prominent work was his ‘Conduct of the Inquisition into Heretical Wickedness’ (Practica Inquisitionis Heretice Pravitatis – Aff.link). It is considered the gold standard as a manual for inquisitors, as his most enthusiastic readers were fellow inquisitors.

In his work comprising volumes, he sought to gather all the relevant information available at the time regarding heretical groups to aid their identification or unmasking. These included Waldensians, Beguins, Cathars, Pseudo-apostles, and more, but it becomes relevant to our purposes here in its treatment of sorcerers.

As we mentioned earlier, sorcerers were not under the jurisdiction of inquisitorial courts unless they were directly involved in heretical acts or doctrines in the first place. This changed in the 1320s by decree or Papal Bull of Pope John the 22nd.

This proclamation brought all demon-worshippers, summoners, those who entered into dealings with them, those who desecrated the sacramental order, and those who modeled wax figures for nefarious purposes into the category of heretics. These individuals and their actions now came under the purview of the Papal courts to be dealt with accordingly.

Related Reading: “Medieval Witch Trials in Europe”– Opens in new tab

Who Were These Sorcerers?

Bernardo Gui’s volume of work, or ‘manual’ detailed a form of questioning designed to help an inquisitor obtain the truth from these ostensibly deceitful heretics. To paraphrase his words,

'the epidemic of sorcerers, demon-summoners, and clairvoyants manifests in various places, preying on the multitudinous fancies and pagan beliefs of the superstitious who fall victim to the malignant influence of erroneous spirits and demonic doctrines.'

As such, they would have to be closely questioned. What knowledge had they? Had they practiced the casting of spells on children? Had they invoked supernatural forces to help otherwise barren women conceive? In their practice, had they fed their subjects objects such as fingernails; hair? Had they achieved the prescience of future events? Healing through enchantments?

In Bernardos’ thinking, however, the most offensive heretical elements involved the desecration of otherwise Christian rituals and practices to achieve profane or magical ends. The use of holy oils or the Holy Host, mimicking the orthodox Catholic sacraments, for example. Or the baptism of waxen figurines in the form of actual people that would then be pierced with needles to inflict harm on the intended target to bring about harm to them.

He also went to great lengths to uncover where these practitioners had picked up their knowledge or training in the heretical arts, the extent of their belief in their efficacy, and exactly who would come to them for their services.

Bernardo Gui would exhort his collegiate readers to question their subjects thoroughly, keeping in mind the individual status and understanding of each in order. Different people were to be approached differently, with men and women being tackled by separate methods.

His exhortations bring us round to the point of our particular interest. In his time, sorcery was not the preserve of any specific gender. There was, however, one magical practice that was the preserve of the male sex alone: necromancy.

Related Reading: The Witch Stereotype and the Crime of Witchcraft – Opens in new tab

Necromancy among the Educated Male Classes of the 14th Century

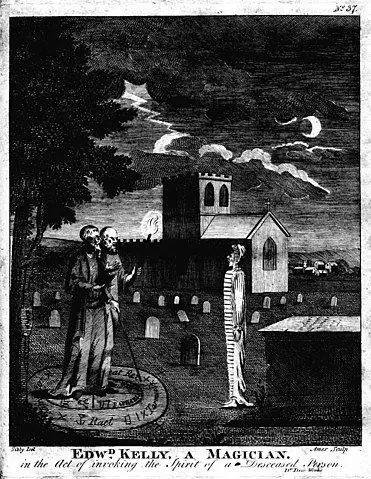

The definition of necromancy, from the Latin ‘nekros’ (corpse) and ‘manteia’ (divination or prophecy), tells it all. It translates literally to ‘divination through the deceased.’ Necromancers would conjure up the spirits of those gone before them to gain knowledge of the future, make use of them as weapons against their fellows, or compel the revelation of hidden information.

For a religion based on the foundation of Christ’s resurrection, bringing back the dead was nothing short of problematic. The recourse of the Church was to classify such phenomena as demonic manifestations, thus leading to the term necromancy gaining a decidedly demonic or negative taint.

The twist in this tale is that necromancers were found overwhelmingly, almost exclusively, in the clerical classes. The Latin language was the exclusive preserve of men and very few men at that. These were men that had received a fraction of clerical instruction (women were not afforded such privileges at the time).

The upshot is that only those who could read Latin would be able to learn the very precise and convoluted incantations involved in necromancy, only to be found in books written in, you guessed it – Latin. Inquisitors such as Nicholas Eymerich outlined in his work, ‘Directorium Inquisitorium,’ how important it was to destroy all confiscated books related to necromancy for this very reason.

The books in question combined with the spoken confessions of uncovered necromancers provided writers such as Eymerich with insight into the practices of these individuals. As we are told, they would baptize wax models, pervert prayers by mixing the names of demons known to them into prayers, offer burnt animal offerings, and explicitly worship demons. In return for their favor, they honored and obeyed them, offering them their allegiance in perpetuity.

While any prudent researcher will hesitate to take people’s word under the duress of intense questioning and probable torture as reliable accounting, the presence up to today of various manuscripts detailing just such rituals and practices lends weighty credence to these accounts. The manuscripts and texts referred to are not the writings of those seeking to eliminate necromancy but the penned guides and directions of necromancers aimed at educating and edifying fellow and prospective necromancers.

It does not stretch the imagination too far to imagine the various benefits a person may accrue by harnessing the supernatural powers of demons. Knowledge of the future, the power to affect fellow human beings (influence their actions, attract their favor, harm them, and so on), and otherwise gain insight into the world around you that is hidden from everyone else are powerful attractions for the prospective necromancer.

It strikes one that none of these purposes seem particularly relatable to the ecclesiastical classes, but there it is. Magic of this nature would always involve conjuration, magic circles, and sacrifices, all practices that call for high levels of mastery.

Related reading: Burning Words, Healing Bodies: How Medieval England Used Written Words to Heal – Opens in new tab

Final Thoughts

The surprising truth at the heart of any study into necromancy and its development is that both sides of the divide agree on it being an essentially forward step in human understanding of the physical and spiritual universe. Advocates and detractors alike acknowledged the power of the rituals involved in the practice.

The essential thinking both sides shared was that certain words recited in a specific order under certain performative conditions (rituals) had the power to summon forces outside the realm of ordinary human capacity. The unsavory reality is that the same can be said of the prayers and rituals in mainstream religious practice.

Rather than fall to the temptation of regarding people living in the medieval ages as backward or naïve in their thinking, our understanding would be better served by noting the level at which this battle was being fought. The most educated men of their times had the desire and capability to access this knowledge. In juxtaposition, only the educated theologians and inquisitors could recognize the dangers posed by it.

Where does that leave us living in the here and now? We are heirs to all the knowledge, precepts, beliefs, and prejudices of those who came before us, and we participate in many of the rituals practiced in our respective communities. Perhaps it’s something to keep in mind the next time you avoid passing beneath a ladder or, dare we mention; you say a prayer.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Resources

- Course, Magic in the Middle Ages by Universitat De Barcelona from Coursera

- Cornell University Library: https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/witchcraftcoll/

- Medieval Sourcebook – Witchcraft Documents: https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/witches1.asp

- Inquisition records: https://www.york.ac.uk/res/doat/

- Inquisition Collection from University of Notre Dame: https://inquisition.library.nd.edu/collections/RBSC-INQ:COLLECTION

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Featured Image: The inside of a jail of the Inquisition, with a priest – Wikimedia Commons