Modern Western magic has roots that trace back to ancient Greek and Persian cultures, where magic—or mageia—was considered a set of mystical practices associated with the foreign “Magi” from Persia. These ancient magi were respected for their esoteric knowledge and wisdom, quickly influencing Greek society and becoming integrated into its religious and philosophical traditions. Yet, even early on, magic was seen as something “Other”—a practice that was often viewed with both fascination and suspicion.

In Western history, magic evolved through different cultural and intellectual stages. During the Renaissance, a resurgence of esoteric thought took place, with Western magic intertwining with Christian mysticism, astrology, and alchemy.

Magic became a part of “natural philosophy,” where philosophers like Marsilio Ficino and Cornelius Agrippa argued that magic could align with Christianity and even enhance understanding of religious truths. From these roots, Western magic grew into a diverse tradition that combines elements of mysticism, spiritual practice, and occult philosophy.

Exploring Magic’s Place Between Religion, Science, and Spirituality

Throughout its evolution, magic has occupied a liminal space between established religion, emerging science, and personal spirituality. In antiquity, it often stood alongside Greek and Roman religious practices, while in the Christian era, it became associated with ideas of demonic power or heretical acts. However, many practitioners—both historically and today—view magic as a means to connect deeply with spiritual and natural forces rather than as a form of opposition to religion.

Magic in the Western tradition became a bridge between religious faith and the curiosity-driven, experimental methods that would later define scientific inquiry. For instance, the concept of “natural magic” suggested that mystical practices could be understood through hidden or “occult” forces in nature. This naturalistic view aligned with early science, and many early scientists engaged in magical practices, believing that understanding these forces could unlock knowledge about the universe.

How Magic Has Shifted in Meaning Over Time

The perception of magic has shifted significantly over centuries. In early Western culture, magic was a respected practice, often associated with wisdom and knowledge brought from foreign lands. As Christianity became the dominant worldview, magic was increasingly portrayed as a deviant or even dangerous force. Figures like Saint Augustine framed it as a form of demonic manipulation, turning the public view of magic toward fear and condemnation.

By the Renaissance, magic experienced a resurgence, blending with intellectual and mystical pursuits and even finding defenders who argued that it held moral and religious value. In modern times, Western magic has experienced yet another transformation.

Today, it is often understood as a personal spiritual practice, appealing to those seeking alternatives to traditional religious frameworks. Magic has become a pathway to personal empowerment, self-discovery, and a means of connecting with unseen forces, evolving from a stigmatized and misunderstood practice into a respected spiritual path for many.

Historical Roots and Influences Shaping Western Magic

The origins of Western magic can be traced back to mageia, a term used in ancient Greece to describe mystical practices often attributed to the Magi, believed to be of Persian origin. Greek society both admired and feared these practitioners, viewing their rituals and beliefs as powerful but foreign.

The Greeks believed mageia could provide wisdom and knowledge that lay beyond their own cultural boundaries. This dual perspective on magic—seen as both insightful and alien—set the stage for the ambivalence that Western culture would continue to hold toward magic.

As Christianity began to spread across Europe, the Greek concepts of magic were reinterpreted within a Christian framework, where some aspects were adopted and others condemned. A new form of magic known as theurgy, or “divine work,” arose.

Theurgy focused on spiritual purification and connection with divine powers and was practiced by Neoplatonist philosophers, who sought enlightenment and divine ascent through their rituals. Unlike other forms of magic, theurgy was viewed as a higher, more acceptable form of mystical practice since it was often aligned with Christian ideals of spiritual transformation.

The Persian Influence: Wandering Magi and the Birth of Magic

The Magi, or Persian priests, played a foundational role in the Western understanding of magic. Originally spiritual leaders in ancient Persia, they were associated with astrology, esoteric knowledge, and ritualistic practices. When the Greeks encountered the Magi, they were struck by their mysterious rituals and deep knowledge, leading the Greeks to consider these practices both exotic and powerful. The Magi were often seen as bearers of secret wisdom, especially in areas such as divination and spiritual knowledge, which the Greeks then absorbed into their own magical traditions.

This influence marked one of the earliest instances where magic was regarded as “foreign,” a perception that would persist as magic evolved in Western culture. The presence of the Magi cemented the idea that magic could be both beneficial and dangerous, depending on how and by whom it was practiced. Their practices symbolized an “outside” knowledge that carried both allure and unease, shaping the Western attitude toward magic as something both desired and feared.

Related reading: Magick through History – Opens in new tab

Renaissance Revival: Christian Kabbalah, Alchemy, and the Rise of “Natural Magic”

During the Renaissance, Western magic experienced a significant revival. Intellectuals and mystics reimagined ancient mystical ideas, leading to the rise of Christian Kabbalah, alchemy, and what became known as “natural magic.”

Christian Kabbalah, inspired by Jewish mystical traditions, sought to uncover hidden meanings in the Bible and connect more closely with the divine. Alchemy, meanwhile, pursued spiritual and material transformation, with practitioners believing they could turn base metals into gold and even attain spiritual enlightenment through chemical processes.

Renaissance thinkers like Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola argued that natural magic could align with Christian teachings and reveal divine truths. Ficino and his contemporaries asserted that certain mystical forces were inherent in nature and could be used for spiritual growth and insight, rather than being connected to demonic powers. This period marked a shift from viewing magic as purely superstitious or dangerous to recognizing it as a field with potential spiritual value and intellectual depth.

Why Arabic Philosophy and Astrology Left a Lasting Mark on Western Magic

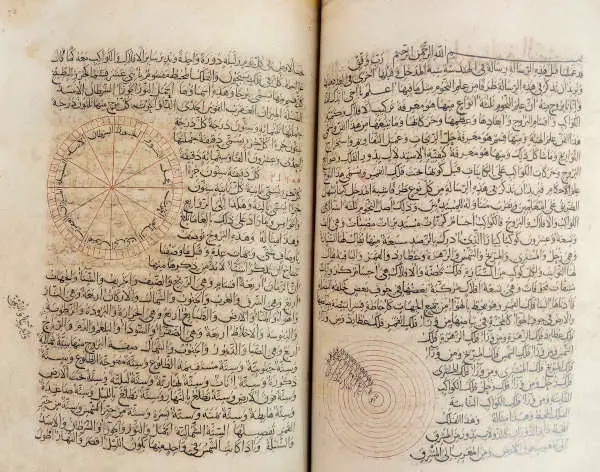

The influence of Arabic philosophy and astrology during the Middle Ages profoundly shaped Western esoteric traditions. As Latin translations of Arabic works began circulating in Europe, European scholars gained access to advanced astronomical, philosophical, and alchemical knowledge from the Islamic world. This knowledge included sophisticated astrological theories and detailed guides to manipulating natural forces, which helped give rise to concepts of natural magic.

Arabic thinkers like Avicenna and Al-Farabi contributed complex ideas on the relationship between the cosmos and humanity, influencing European thinkers to consider the interconnectedness of the universe. Astrology, in particular, became a core element of Western magic, as it was believed that understanding and aligning with celestial movements could impact earthly events and human affairs.

The emphasis on correspondences between celestial and earthly realms from Arabic philosophy helped reinforce the idea of magic as a science rooted in natural laws, setting the groundwork for the Western magical practices that would flourish during the Renaissance.

Check out our recommendations at “Occult Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Library“

How Christianity Shaped Society’s Perception of Magic

As Christianity spread across the Roman Empire and beyond, it brought new interpretations and values that would deeply impact how magic was perceived. Early Christians distinguished between apostolic miracles, which they believed were empowered by God, and pagan or magical practices, which they saw as derived from deceptive or demonic forces.

In the context of a religious culture where miraculous acts were already familiar, Christianity positioned its own miracles as divine interventions in direct opposition to the “false” magic associated with pagan rites and rituals.

The Christian view of miracles as acts of divine will created a clear boundary, casting pagan and magical acts as inferior or even spiritually dangerous. This separation helped strengthen Christianity’s identity against competing religious practices, especially as pagan traditions continued to influence local beliefs. Christian leaders argued that miracles enacted by saints or prophets served to affirm God’s authority, while magic was condemned as an attempt to manipulate supernatural forces independently of God’s blessing.

Augustine’s Influence on Defining Magic as Demonic

One of the most influential figures in shaping the Christian perspective on magic was Saint Augustine, whose writings cast magic in a decidedly negative light. In City of God and On Christian Doctrine, Augustine argued that any supernatural act not sanctioned by God was inherently suspect and likely to be influenced by demonic forces.

He asserted that even so-called theurgy, or high magic aimed at divine communion, was nothing more than disguised necromancy. For Augustine, magic was fundamentally deceptive and morally dangerous, drawing practitioners into illicit and harmful spiritual realms.

Augustine’s stance solidified the association between magic and demonic activity in Christian thought. His view that magic represented an insidious form of idolatry—one that lured people away from faith in God toward reliance on occult forces—set the tone for centuries of Christian opposition to magical practices. His influence extended across medieval Europe, where his ideas formed the theological foundation for later condemnations of magic and witchcraft, framing them as acts of rebellion against divine authority.

The Catholic Church’s Stance on Magic and Occult Practices

Building on Augustine’s teachings, the Catholic Church developed a rigorous stance against magic, viewing it as a profound threat to both individual souls and social order. Church authorities deemed any attempt to harness supernatural powers outside of the Christian context as a violation of the First Commandment: “You shall have no other gods before Me.”

The belief that magic relied on demons or spirits outside God’s influence gave rise to strict Church doctrines that condemned magic as inherently sinful and forbidden.

In the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church’s condemnation of magic grew even harsher. Under canon law, sorcery and witchcraft became grave offenses, with the Church often leading the charge in prosecuting and punishing alleged practitioners. Rituals and charms, even if benign, were seen as forms of superstition that could lead believers away from God.

By defining magic as inherently malevolent, the Church reinforced the idea that only faith and religious obedience, not occult practices, could bring spiritual fulfillment. This firm stance laid the groundwork for later witch hunts and widespread fears about magical practices in Europe, further embedding the association of magic with evil and demonic forces.

Related reading: Ancient Magic: From Divine Rituals to Dark Superstitions – Ancient Rome and Early Christianity – Opens in new tab

The Rise of “Natural Magic” and the Shift from Demonic to Scientific Magic

During the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, the concept of magia naturalis, or “natural magic,” began to shift the view of magic away from its association with demonic forces. Proponents of natural magic argued that certain mystical practices could operate within the boundaries of natural laws rather than relying on supernatural or infernal powers.

This form of magic, they claimed, was grounded in an understanding of hidden forces within nature—forces that could be harnessed for healing, insight, and transformation. Unlike sorcery or witchcraft, which were condemned as demonic by the Church, natural magic was seen by some as a means of unlocking divine wisdom embedded within the natural world.

Natural magic practitioners focused on the influence of celestial bodies, herbs, minerals, and other natural elements to achieve specific effects. Figures like Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola defended natural magic, positioning it as compatible with Christianity and even capable of enhancing one’s connection to God.

By framing magic as an exploration of the natural world rather than a pact with demonic forces, natural magic created an intellectual space where magical practices could be studied and discussed without automatically incurring suspicion of heresy.

The Influence of Astrology on Early European Magic

Astrology became one of the most significant components of natural magic during the Renaissance. Based on the belief that celestial bodies exerted influence over earthly events, astrology proposed that humans could understand and potentially control aspects of their lives by studying planetary alignments and movements. Early European magic incorporated astrological principles, with practitioners using charts and symbols to predict events, guide decision-making, and even heal or protect individuals.

Astrological magic relied on the concept of cosmic harmony and correspondences, which suggested that specific planetary forces could be harnessed for personal benefit. By invoking these cosmic alignments, natural magicians believed they could tap into an order that was built into the universe by divine intention.

This approach allowed astrology and related forms of magic to be viewed as quasi-scientific, giving them a respectability that distinguished them from practices condemned as sorcery. The Church, however, remained cautious of astrology’s influence, fearing that it might lead individuals to place undue faith in the stars rather than in God’s will.

Related reading: Beyond the Shadows: How Occultism Shaped Politics, Science, and Social Change – Opens in new tab

The Church’s Uneasy Relationship with Natural and Ritual Magic

Although natural magic attempted to align itself with Christian ideals, the Church maintained a cautious and often uneasy stance toward it. While some clergy and scholars acknowledged that the study of natural forces could reveal God’s creation, the line between acceptable natural magic and forbidden demonic magic remained blurred. Many Church authorities worried that even natural magic could become a gateway to more dangerous practices, leading individuals down a path of heresy or idolatry.

The use of rituals and symbols in natural magic further complicated the Church’s response. Rituals invoking planetary influences or using consecrated items to achieve a desired outcome mirrored Christian liturgical practices, making it difficult to determine whether such rituals honored God or sought to control supernatural forces outside His sanction. As a result, the Church generally tolerated certain aspects of natural magic but remained vigilant, often condemning specific practices or practitioners who were seen as straying too close to heresy.

This uneasy relationship with natural and ritual magic would continue to evolve, especially as scientific inquiry grew. By the early modern period, natural magic began to overlap with early scientific experimentation, creating a pathway for the eventual separation of science from mystical traditions and leading to the “scientific magic” that laid the groundwork for modern scientific practices.

The Dark Ages to the Enlightenment: How Magic Was Simultaneously Condemned and Practiced

In the Middle Ages, Western society’s relationship with magic was complex, marked by both intense fear and deep fascination. The Church’s teachings positioned magic as dangerous and sinful, warning that its practice opened the door to demonic forces. Yet, magic’s promise of hidden knowledge and power attracted widespread curiosity, even within Christian communities. Legends, folklore, and tales of sorcery filled the popular imagination, giving magic an undeniable allure despite its condemnation by religious authorities.

While the Church fiercely opposed sorcery and what it deemed heretical practices, there were still those who believed in the potential benefits of certain magical acts, such as healing or protection against evil. Many people turned to local healers or “cunning folk” who used charms and herbal remedies that bordered on magical practices. This mixture of prohibition and fascination kept magic alive during the Middle Ages, as people oscillated between fear of its potential dangers and respect for its perceived powers.

The Duality of Magic During the Renaissance: From Alchemy to Exorcism

The Renaissance ushered in a renewed interest in mystical and esoteric knowledge, with magic occupying a dual role in society. On one hand, intellectuals explored alchemy, astrology, and the Christian Kabbalah as tools to access divine mysteries, believing these practices could lead to spiritual enlightenment and a deeper understanding of the natural world. Figures like Paracelsus and Cornelius Agrippa argued that magic, especially “natural magic,” was a legitimate means of harnessing the secrets of creation and that it could coexist with Christian faith.

On the other hand, the Church maintained a strong stance against forms of magic that it perceived as harmful or sacrilegious. Rituals involving spirits or divination were met with suspicion, and exorcism became a common practice to combat what were believed to be demonic influences on individuals and communities. Thus, while the Renaissance celebrated intellectual and mystical pursuits, magic still carried the potential for spiritual peril in the eyes of religious authorities. This tension highlighted the dual nature of magic during this era—it was both a revered path to wisdom and a risky practice that could invite condemnation.

Magic as a Practice Among Europe’s Intellectual and Religious Elite

Magic was not only practiced by common folk but also embraced by Europe’s intellectual and religious elite, who saw it as a pathway to profound knowledge. Scholars, clergy, and even royalty studied occult practices, often framing them as scientific or theological investigations. For many intellectuals of the time, magic was seen as a form of advanced knowledge that could unlock the mysteries of the universe, offering insights that went beyond the limits of traditional theology.

This acceptance of magic among the elite allowed it to flourish in academic and spiritual circles. Christian scholars explored mystical practices, attempting to reconcile magic with religious teachings. Alchemists pursued not only the transformation of metals but also spiritual transformation, seeking the “philosopher’s stone” as a symbol of enlightenment. This intellectual pursuit of magic allowed it to survive, develop, and even gain a measure of legitimacy, setting the stage for its eventual evolution into early scientific practices and philosophies during the Enlightenment.

Final Thoughts

The journey of Western magic reflects its ability to endure, evolve, and inspire despite centuries of transformation and challenge. From its early days as an enigmatic and often forbidden practice to its later incorporation into intellectual and religious life, magic has demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability.

Each phase—from ancient Greek and Persian influences to the Renaissance embrace of natural magic—has left a distinct mark, shaping what we now understand as modern Western magic. This enduring tradition, rooted in diverse practices and philosophies, remains a source of fascination and personal exploration, connecting contemporary practitioners to a history that spans centuries and cultures.

Check out our recommendations at “Occult Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Library“

This article is based on: “Aries: Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism, 12 ( 1 ), special issue on Modern Western Magic, guest edited by Henrik Bogdan”

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Featured image by Depositphotos