“Grimoires are books that contain a mix of spells, conjurations, natural secrets and ancient wisdom. Their origins date back to the dawn of writing and their subsequent history is entwined with that of the religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, the development of science, the cultural influence of print, and the social impact of European colonialism.” Owen Davies

As long as humanity has had beliefs in a higher power, the use of magic, spells, curses, and incantations have featured widely across cultures.

A number of influential texts or ‘grimoires’ (textbooks of magic) were developed over the centuries, many of which became the books of choice for secret societies and occult organizations that endured well into the twentieth century.

Witchcraft of some sort has probably existed since humans first banded together in groups. Simple sorcery (or the use of magic accessible to ordinary people), such as setting out offerings to helpful spirits or using charms, can be found in almost all traditional societies.

Prehistoric art depicts magical rites to ensure successful hunting and also seems to depict religious rituals involving people dancing in animal costumes.

Shamanism, the practice of contacting spirits through dream work and meditative trances, is probably the oldest religion, and early shamans collected much knowledge about magic and magical tools.

Related reading: Magick through History – Opens in new tab

Witches of ancient Sumeria and Babylonia invented an elaborate Demonology. They had a belief that the world was full of spirits and that most of these spirits were hostile.

Each person was supposed to have their own spirit which would protect them from demons and enemies, which could only be fought by the use of magic (including amulets, incantations, and exorcisms).

Western beliefs about witchcraft grew largely out of the mythologies and folklore of ancient peoples, especially the Egyptians, Hebrews, Greeks, and Romans.

Witches in ancient Egypt purportedly used their wisdom and knowledge of amulets, spells, formulas, and figures to bend the cosmic powers to their purpose or that of their clients. (Further reading: Amulets and Talismans-Differences and Similarities)

The Greeks had their own form of magic, which was close to a religion, known as Theurgy (the practice of rituals, often seen as magical in nature, performed with the intention of invoking the action of the gods, especially with the goal of uniting with the divine and perfecting oneself).

Another lower form of magic was “Mageia”, which was closer to sorcery, and was practiced by individuals who claimed to have knowledge and powers to help their clients, or to harm their clients’ enemies, by performing rites or supplying certain formulas. (Further Reading: “Magick – Definition and Etymology”)

Some argue, however, that the real roots of witchcraft and magic as we know it come from the Celts, a diverse group of Iron Age tribal societies that flourished between about 700 BC and 100 AD in northern Europe (especially the British Isles).

Believed to be descendants of Indo-Europeans, the Celts were a brilliant and dynamic people, gifted artists, musicians, storytellers, and metalworkers, as well as expert farmers and fierce warriors much feared by their adversaries, the Romans.

They were also a deeply spiritual people, who worshipped both a god and a goddess. Their religion was pantheistic, meaning they worshipped many aspects of the “One Creative Life Source” and honored the presence of the “Divine Creator” in all of nature.

They believed in reincarnation and that after death they went to the Summerland for rest and renewal while awaiting rebirth. By about 350 BC, a priestly class known as the Druids had developed, who became the priests of the Celtic religion as well as teachers, judges, astrologers, healers, midwives, and bards.

The religious beliefs and practices of the Celts, their love for the land, and their veneration of trees (the oak in particular) grew into what later became known as Paganism, although this label is also used for the polytheistic beliefs of the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans.

Blended over several centuries with the beliefs and rituals of other Indo-European groups, this spawned such practices as concocting potions and ointments, casting spells, and performing works of magic, all of which (along with many of the nature-based beliefs held by the Celts and other groups) became collectively known as witchcraft in the Medieval Period.

Humankind has long dabbled in the supernatural, lured by the promise of obtaining power and enlightenment. Several texts have been devoted to this practice, outlining complicated and mysterious rituals that were presented as the key to achieving communion with otherworldly spirits.

Here we feature 9 Powerful Ancient Magic Spellbooks, you need to explore.

The Greek Magical Papyri

The Greek magical papyri (Latin Papyri Graecae Magicae, abbreviated PGM) is the name given by scholars to a body of papyri from Greco-Roman Egypt which each contains a collection of magical spells, formulae, hymns, and rituals.

The materials in the papyri date from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD. The manuscripts came to light through the antiquities trade, from the 18th century onwards.

The texts were published in a series, and individual texts are referenced using the abbreviation PGM plus the volume and item number. Each volume contains a number of spells and rituals.

According to Hans Dieter Betz, the Greek magical papyri known today only present a small fraction of what once existed, in forms of books. Betz cites Ephesus in the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 19: 10) for book burnings. On the account of Suetonius, Augustus ordered the burning of 2,000 magical scrolls in 13 BC.

Betz states, “As a result of these acts of suppression, the magicians and their literature went underground. The papyri themselves testify to this by the constantly recurring admonition to keep the books secret…

The religious beliefs and practices of most people were identical with some form of magic, and the neat distinctions we make today between approved and disapproved forms of religion-calling the former “religion” and “church” and the latter “magic” and “cult”-did not exist in antiquity except among a few intellectuals.

It is known that philosophers of the Neopythagorean and Neoplatonic schools, as well as Gnostic and Hermetic groups, used magical books and hence must have possessed copies. But most of their material vanished and what we have left are their quotations.”

The pages contain spells, recipes, formulae, and prayers, interspersed with magic words and often in shorthand, with abbreviations for the more common formulae.

These spells range from impressive and mystical summonings of dark gods and daemons to folk remedies and even parlour tricks; from portentous, fatal curses, to love charms, cures for impotence and minor medical complaints.

Throughout the spells found in the Greek Magical Papyri, there are numerous references to figurines. They are found in various types of spells, including judicial, erotic and just standard cursing that one might associate with Haitian voodoo (“Vodou”).

Related reading: Frequently Asked Questions about Magick – Opens in new tab

The figurines are made of various materials, usually corresponding to the type of spell, but often with liminal properties, as is frequent in a number of elements of Greek Magic.

Such figurines have been found “throughout the Mediterranean basin”, usually in places that the ancient Greeks associated with the underworld; “graves, sanctuaries or bodies of water”, all stressing the liminality of Greek magic. Some have been discovered in lead coffins, upon which the spell or curse has been inscribed.

The magical papyri include instructions on how to summon a headless demon, open doors to the underworld and, protect yourself from wild beasts. Perhaps most tantalizing of all they describe how to summon a supernatural being an entity from another world who does whatever you desire.

The most commonly found spells in the papyri, are divination spells which are ceremonies that offer you visions of the future. One of its most well-known passages provides instructions for how to forecast upcoming events, using an uncorrupted and pure child. After being placed into a deep trance the child sees future images flickering in a flame.

Among the papyri’s Most famous components is the Mithras Liturgy. This ceremony describes how to ascend through seven higher planes of existence and communicate with the deity Mithras.

Sworn Book Of Honorius

The “Sworn Book of Honorius” (Liber Juratus Honorii in Latin) is one of the oldest and most influential texts of Medieval magic. The prologue says the text was compiled to help preserve the core teachings of the sacred magic, in the face of intense persecution by church officials. This may be a reference to the actions of Pope John XXII

It is supposedly the product of a conference of magicians who decided to condense all of their knowledge into one volume. In 93 chapters, it covers a large variety of topics, from how to save one’s soul from purgatory to catching thieves or finding treasures.

It has many instructions on how to conjure and command demons, to work other magical operations, and knowledge of what lies in Heaven among other highly sought information.

Is rumored to be the work of Honorius of Thebes, a mysterious possibly mythological figure who has never been identified. The book begins with a scathing criticism of the Catholic Church. The church a staunch enemy of the dark arts has been corrupted by the devil whose goal is to doom humanity by ridding the world of the benefits of magic.

The Sworn Book of Honorius is widely considered to be one of the most influential magic texts of the medieval period. As its title indicates, students were sworn to secrecy before being given access to this text.

Only three copies of the book can be made. Anyone in possession of the book, who cannot find a worthy magician to inherit it, must take it to his grave and all adherents must utterly forbear the company of women.

Like many other grimoires, its rituals focused largely on summoning angels, demons, and other spirits, to gain knowledge and power. By repeating long-winded orations, it promises to the practitioner to obtain a wealth of scintillating abilities.

These powers range from, causing floods, and destroying kingdoms, to knowing the hour of your death.

Among its most malign spells, there are some that give you the power to cause sickness to whoever you want, to cause discord and debate, and to kill everyone you desire.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (Grimoire)

Pseudomonarchia Daemonum, also known as the False Hierarchy of Demons, is a great compendium from the 16th century dictating the names of sixty-nine demons.

The title itself indicates that the demonic monarchy depicted in the text is false, in many ways an insult to those who determinedly believe in the demons of hell.

The Pseudomonarchia Daemonum is an index of demons that appeared, as an appendix, in Johann Weyer’s Praestigiis Daemonum. It is the primary source for the demons listed in many other grimoires, including the Lesser Key of Solomon.

The book was written before The Lesser Key of Solomon and has some differences. There are sixty-nine demons listed (instead of seventy-two, evoked by the ancient King Solomon), and the order of the spirits varies, as well as some of their characteristics.

The demons Vassago, Seere, Dantalion, and Andromalius are not listed in this book, while Pruflas is not listed in The Lesser Key of Solomon. Pseudomonarchia Daemonum does not attribute seals to the demons, as The Lesser Key of Solomon does.

The purpose of this book is to act as a grimoire, also known as a spellbook, to provide the reader with important facts about demons that might be summoned, such as what they look like or what abilities they might possess.

For example:

Volac is a demon described as an angelically winged boy riding a two-headed dragon, attributed to the power of finding treasures.

Aamon is a Marquis of Hell who governs forty infernal legions. He is also an entity many looked to reconcile friends and foes and procure love for those seeking it.

Forneus is a Great Marquis of Hell and has twenty-nine legions of demons under his rule. He teaches Rhetoric and languages, gives men a good name, and makes them beloved by their friends and foes.

Pruflas is a Great Prince and Duke of Hell who has twenty-six legions of demons under his command. He causes men to commit quarrels, discord, and falsehood and should be never admitted into any place, but if conjured, he gives truthful, generous answers to the conjurer’s questions.

However, Weyer was a devout Christian who approached the prospect of conjuring these hellbound spirits with great caution. He censored the text, omitting necessary parts of the rituals and the more powerful demons, like Lucifer, in order to protect readers from their own curiosity.

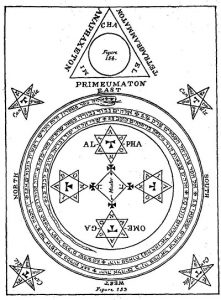

The Lesser Key of Solomon

The Lesser Key of Solomon or Lemegeton Clavicula Salomonis (the Clavicula Salomonis or Key of Solomon is an earlier book on the subject), is an anonymous 17th-century grimoire, and one of the most popular books of demonology.

It has also long been widely known as the Lemegeton, although that name is considered incorrect because it depends on faulty Latin.

It appeared in the 17th century, but much was taken from texts of the 16th century, including the Pseudomonarchia Daemonum, by Johann Weyer, and late-medieval grimoires. It is likely that books by Jewish kabbalists and Muslim mystics were also inspirations. Some of the material in the first section, concerning the summoning of demons, dates to the 14th century or earlier.

The book claims that it was originally written by King Solomon, although this is certainly incorrect. The titles of nobility (such as the French Marquis or Germanic Earl) assigned to the demons were not in use in his time, nor were the prayers to Jesus and the Christian Trinity included in the text (Solomon’s birth predated Jesus Christ’s birth by more than 900 years).

The Lesser Key of Solomon contains detailed descriptions of spirits and the conjurations needed to invoke and oblige them to do the will of the conjurer (referred to as the “exorcist”).

It details the protective signs and rituals to be performed, the actions necessary to prevent the spirits from gaining control, the preparations prior to the invocations, and instructions on how to make the necessary instruments for the execution of these rituals.

The several original copies extant vary considerably in detail and in the spellings of the spirits’ names. Contemporary editions are widely available in print and on the Internet.

The Lesser Key of Solomon is divided into five parts:

Ars Goetia

The first section, called Ars Goetia, contains descriptions of the seventy-two demons that Solomon is said to have evoked and confined in a brass vessel sealed by magic symbols, and that they obliged to work for him. It gives instructions on constructing a similar brass vessel and using the proper magic formula to safely call up those demons.

It deals with the evocation of all classes of spirits, evil, indifferent and good; its opening Rites are those of Paimon, Orias, Astaroth and the whole cohort of.

Ars Theurgia Goetia

The Ars Theurgia Goetia (“the art of goetic theurgy”) is the second section of The Lesser Key of Solomon. It explains the names, characteristics, and seals of the 31 aerial spirits (called chiefs, emperors, kings, and princes) that King Solomon invoked and confined, the protections against them, the names of their servant spirits, called dukes, the conjurations to invoke them, and their nature, that is both good and evil.

Their sole objective is to discover and show hidden things, the secrets of any person, and obtain, carry, and do anything asked to them meanwhile they are contained in any of the four elements (Earth, Fire, Air, and Water). These spirits are given in a complex order in the book, and some of them have spelling variations according to the different editions.

Check out our collection of “Free Online Audiobooks” and many free resources in our “Free Library”

Ars Paulina

The Ars Paulina (The Art of Paul) is the third part of The Lesser Key of Solomon. According to the legend, this art was discovered by the Apostle Paul, but in the book is mentioned as the Pauline Art of King Solomon. The Ars Paulina was already known since the Middle Ages. It is divided into two chapters in this book.

The first chapter refers to how to deal with the angels of the several hours of the day (meaning day and night), their seals, their nature, their servants (called Dukes), the relation of these angels with the seven planets known at that time, the proper astrological aspects to invoke them, their names (in a couple of cases coinciding with two of the seventy-two demons mentioned in the Ars Goetia), the conjuration and the invocation to call them.

The second chapter concerns the angels that rule over the zodiac signs and each degree of every sign, their relation with the four elements, Fire, Earth, Water, and Air, their names, and their seals. These are called here the angels of men, because all persons are born under a zodiacal sign, with the Sun at a specific degree of it.

Ars Almadel

The Ars Almadel is Book Four of the Lesser Key of Solomon, also known as the Lemegeton, a significant grimoire of demonology compiled in the 17th century by an unknown author.

This particular book of the Legemeton provides a blueprint for constructing an Almadel—a magical wax altar, somewhat like an Ouija board, that allows you to communicate with angels.

The magical Almadel alter, has roots in Ancient Jewish and Arabian Magick, used to invoke and communicate with a specific group of angels with a crystal ball.

The Almadel consists of a square plate of wax engraved with magical names and characters, which rests upon four candles constructed with special feet for suspending the plate in the air. The plate has holes in the corners, and mastic incense is burned beneath it so that the smoke flows through the holes and the angel descends.

The angels in the system relate to the seasons and the year’s astrological calendar.

The Almadel is composed of four Altitudes, or “Choras,” each of which corresponds to a unique set of angels with different domains. The text provides the names of the angels of each Chora (Gelomiros and Aphiriza, for example), the proper way to direct your requests to them (ask only what is “just and lawful”), and the best calendar dates for invoking them.

It also includes brief physical descriptions of these angelic manifestations. The Angels of the Third Chora, for example, come in the form of “little women dressed in green and silver” wearing crowns made of bay leaves.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Ars Notoria

The Ars Notoria (The Notable Art) is the fifth and last part of The Lesser Key of Solomon, dating back to the 13th century. It was indeed a grimoire known since the Middle Ages. The book asserts that this art was revealed by the Creator by means of an angel to King Solomon.

It contains a collection of prayers (some of them divided into several parts) mixed with kabbalistic and magical words in several languages (i.e. Hebrew, Greek, etc., and some inventions), how the prayers must be said, and the relation that these rituals have to the understanding of all sciences.

It mentions the aspects of the Moon in relation to the prayers. It also says that the prayers act as an invocation to God’s angels. According to the book, the correct spelling of the prayers gives the knowledge of the science related to each one and also a good memory, stability of mind, and eloquence. This chapter prevents on the precepts that have to be observed to obtain a good result.

Those who practice liberal arts, such as arithmetic, geometry, and philosophy, are promised a mastery of their subject if they devote themselves to the Ars Notoria. Within, it describes a daily process of visualization, contemplation, and orations, intended to enhance the practitioner’s focus and memory.

One of the prayers said to have been called Artem Novam (in Latin) by King Solomon, makes mention to Jesus. Other prayers mention God Father, his son Jesus, and the Holy Ghost, precisely the Christian Trinity. Another mentions the Apostles and martyrs, and another one the Lord’s Prayer.

Finally, it tells how King Solomon received the revelation from the angel.

Arbatel De Magia Veterum

The Arbatel de magia veterum (Arbatel: Of the Magic of the Ancients) is a Renaissance-period grimoire – a textbook of magic – and one of the most influential works of its kind.

The Arbatel is claimed to have been written in 1575 AD. (This date is supported by textual references dating from 1536 through 1583), and although the author remains unknown, it has been speculated that it was written by a man named Jacques Gohory, a Paracelsian (a group who believed in and followed the theories of Paracelsus).

It is unlike some other occult manuscripts that contain dark magic and malicious spells. Instead, it’s a comprehensive handbook of spiritual advice and aphorisms. The Arbatel contains guidance on how to live an honest and honorable life.

There are many different opinions about the origin of the title.

A.E. Waite assumes that the title is from the Hebrew: ארבעתאל (or Arbotal) as the name of an angel the author would have claimed to have learned magic from. Adolf Jacoby believed the name to be a reference to the Tetragrammaton, via the Hebrew ARBOThIM (fourfold) and AL (or God). Peterson, mentioning the above possibilities, also suggests that the title might be the author’s pseudonym.

The Arbatel mainly focuses on the relationship between humanity, celestial hierarchies, and the positive relationship between the two. The Olympian spirits featured in it are entirely original.

A.E. Waite, quite clear of the Christian nature of the work (if dissatisfied with its ideas of practical magic), writes that the book is devoid of black magic and without any connection to the Greater or Lesser Keys of Solomon.

Unlike other grimoires, the Arbatel exhorts the magus to remain active in their community (instead of isolating themselves), favoring kindness, charity, and honesty over remote and obscure rituals.

The Arbatel looks very much like a mystical self-help book, stressing the importance of Christian godliness, productivity, positive thinking, and using magic to help instead of harm. Its kernels of wisdom include “live for yourself and the Muses; avoid the friendship of the multitude” and “flee the mundane; seek heavenly things.”

The Bible is the source most often quoted and referred to throughout the work (indeed, the author appears to have almost memorized large portions of it, resulting in paraphrases differing from the Vulgate).

The Arbatel cannot be understood if separated from the philosophy of Paracelsus, who appears to have coined the term “Olympic spirits”, and was the inspiration for the Arbatel’s understanding of elementals (including Paracelsus’s gnomes and the uniquely Paracelsian “Sagani”), the macrocosm and microcosm, and experimentation combined with respect for ancient authorities.

Indeed, the Arbatel is both broadly and deeply rooted in classical culture including Ancient Greek philosophy, the Sibylline oracles, and Plotinus in addition to the contemporaneous theology and occult philosophy of figures such as Iovianus Pontanus and Johannes Trithemius.

The Arbatel reveals a series of rituals to invoke the seven heavenly governors and their legions, who rule over the provinces of the universe. The governors include Bethel, who brings miraculous medicines, Phalec, who brings honor in war, and Aratron, who “maketh hairy men.”

However, the ability to perform these rituals is only for a person who is “born to magic from his mother’s womb.” All others, the Arbatel warns, are powerless imitators.

In addition to angels and archangels, the Arbatel mentions a coterie of other helpful elemental spirits that exist beyond the veil of the physical world, including pygmies, nymphs, dryads, sylphs (tiny forest people), and sagani (magical mortal spirits that inhabit the elements).

In many ways, Arbatel is unique among texts on magic. Unlike the vast majority of writings, it is clear, concise, and elegantly written. The practical instructions are straightforward and undemanding.

When it first appeared in 1575, it attracted the attention of people with a surprisingly broad range of agendas, including some of the finest minds of the time. Often quoted and reprinted, both praised and condemned, its impact on Western esoteric philosophy has been called “overwhelming.”

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Galdrabok

Perhaps not as well-known as other grimoires, the Galdrabok, an Icelandic ‘book of magic’, is one of the most important surviving documents for the practices and understanding of occult practices in Iceland in the late Medieval era.

It offers a unique insight into the various elements that contributed to a national magical tradition in Iceland at the time of its compilation.

The Icelandic grimoire originated in the 16th century, and according to Dr. Flowers, no other document of comparable age gives so many details about the archaic Germanic gods, cosmology, and magical practices, as this manuscript.

The Galdrabok is a collection of 47 spells compiled by four different people, possibly starting in the late 16th century and going on until the mid-17th century. The first three scribes were Icelanders, and the fourth was a Dane working from Icelandic material.

The manuscript does not represent a comprehensive composition but rather it is a collection of spells that appear to be randomly pieced together.

The Galdrabok is essentially composed of two kinds of spells: groups of spells working by means of prayer formula, invoking higher powers, and by which the magical end is effected indirectly. Only a small number of spells in the Galdrabok (8 in total) fall into this category.

The second group consists of more commonly used spells which supposedly worked as a direct expression of the magician’s will, expressed in the forms of signs, and written, or spoken formulas.

Related reading: Common Mistakes People Make When Learning Magick – Opens in new tab

Like most Icelandic magic of the period, the Galdrabok relies heavily on staves—runes that have magical properties when carried on the body, carved on objects, or written out. Among the staves drawn in the Galdrabok are ones to attract and curry the favor of powerful men, incite fear in your enemies, and put someone to sleep.

The majority of the spells found in the Galdrabok are “apotropaic spells,” benign remedies designed to protect the practitioner and heal various maladies. These include tiredness, difficulty with childbirth, headaches, and insomnia. Other spells are pretty peculiar in nature.

Spell 46, the hilariously titled “Fart Runes,” is a stave that will strike your enemy with “bad gas . . . and all of these will plague thy belly with great farting . . . may thy farting never stop.” Some are downright sinister.

Spell 27, for example, when drawn on someone’s food, will make them sick and unable to eat all day, while Stave 30 is designed to kill another person’s animal. There are also staves to prevent your house from unwanted visitors, catch thieves, and “get satisfaction in a legal case.”

Three of the spells in the Galdrabok do not involve either prayers or signs but are more like a recipe, or a potion, using natural substances that were supposed to work with magical effects. This kind of natural magic is often found in “leech-books”, or physician’s manuals.

The book was first published in 1921 by Natan Lindqvist in a diplomatic edition and with a Swedish translation. An English translation was published in 1989 by Stephen Flowers and a facsimile edition with detailed commentary by Matthías Viðar Sæmundsson in 1992.

In 1995 Flowers produced a second retitled edition of his book and with the assistance of Sæmundsson corrected many translations and added many more notes and commentaries.

Picatrix

This Art is called Magic…[It] is not easy to understand, and it is hidden from the simpleminded.

Magic is a divine power, affecting by original causes…Picatrix

The Picatrix is an ancient Arabian book of astrology and occult magic dating back to the 10th or 11th century, which has gained notoriety for the obscene nature of its magical recipes.

The Picatrix, with its cryptic astrological descriptions and spells covering almost every conceivable wish or desire, has been translated and used by many cultures over the centuries and continues to fascinate occult followers from around the world. (Further reading: Occult Q&A By Manly P. Hall)

Originally written in Arabic, titled Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm, which translates to “The Aim of the Sage” or “The Goal of the Wise.” Most scholars believe it originated in the 11th century, although there are well-supported arguments that date it to the 10th.

Eventually, the Arabic writings were translated into Spanish, and later into Latin in 1256 for the Castilian king Alfonso the Wise. At this time it took on the Latin title Picatrix.

Picatrix is a strange mixture of the most exalted philosophy and the crassly material, explanations of the nature of the One and “confections” composed of blood, brains, and urine. We can, however, clearly perceive the influence of the Harranian Sabians, who pursued their worship of the astral deities and the tradition of Hermetic philosophy well into the Middle Ages.

The Harranians added much to the astrology of the advanced Islamic civilization which flourished between 800-1400 A.D. and produced such well-known astrologers as Thabit Ibn Qurra, Al-Sufi, and the alchemist, Jabir ibn Hayyyan, known to the West as Geber.

Picatrix is a compilation of many earlier works and represents, along with De Imaginibus “On Images” of Thabit Ibn Qurra, the height of astrological magic in terms of complexity and scope. Picatrix explains not only how to create and ensoul magical statues and talismans, but even speaks of whole cities constructed using the principles of astrological magic.

This combination of practical application and theoretical rigor made Picatrix a key source for Renaissance mages like Cornelius Agrippa and Marsilio Ficino. You can read a scholarly account of the importance of Picatrix by Eugenio Garin.

The book spans a mammoth 400 pages of astrological theory. Alongside are spells and incantations to channel the occult energies of planets and stars to achieve power and enlightenment. The text is composed of both magic and astrology.

The Picatrix is perhaps most notorious for the obscenity of its magic recipes. These gruesome and potentially deadly concoctions are designed to induce altered states of consciousness and out-of-body experiences. Not for the faint of the heart, their ingredients include blood, bodily excretions, and brain matter mixed with copious amounts of hashish, opium, and psychoactive plants

For example, the spell for “Generating Enmity and Discord” reads:

“Take four ounces of the blood of a black dog, two ounces each of pig blood and brains, and one ounce of donkey brains. Mix all this together until well blended. When you give this medicine to someone in food or drink, he will hate you.”

Related Reading: How to Use Bibliomancy for Guidance and Inspiration (New Modern Tool to Use)– Opens in new tab

The Black Pullet

The Black Pullet (La poule noire) is a grimoire that proposes to teach the “science of magical talismans and rings”, including the art of necromancy and Kabbalah. It is believed to have been written in the 18th century by an anonymous French officer who served in Napoleon’s army.

The text takes the form of a narrative centering on the French officer during the Egyptian expedition led by Napoleon (referred to here as the “genius”) when his unit is suddenly attacked by Arab soldiers (Bedouins).

The French officer manages to escape the attack but is the only survivor. An old Turkish man appears suddenly from the pyramids and takes the French officer into a secret apartment within one of the pyramids. He nurses him back to health whilst sharing with him the magical teachings from ancient manuscripts that escaped the “burning of Ptolemy’s library”.

The Black Pullet focuses on the study of magical talismans, special objects engraved with mystical words that protect and empower the wearer. The Pullet includes detailed instructions for how to construct talismans out of bronzed steel, silk, and special ink.

Among these invocations is a spell to call upon a djinn, a creature made of smoke and fire who will bring you, true love. If your ambitions are slightly more cynical, then the Pullet also provides talismans that will force “discreet men” to tell you their secrets, allow you to see behind closed doors, and destroy anyone who is plotting against you.

The apex of the book’s mystical teachings is acquiring the Black Pullet itself. Perhaps the most interesting magical property claimed in the book is the power to produce the Black Pullet, otherwise known as the Hen that lays Golden Eggs.

The grimoire claims that the person who understands and attains the power to instruct the Black Pullet will gain unlimited wealth. The notion of such a lucrative possession has been reflected throughout history in fables, fairy tales, and folklore.

The Book Of Abramelin The Mage

Written in the 15th century, the Book of Abramelin the Mage is one of the most prominent, mystical esoteric grimoires, of Kabbalistic knowledge of all time. It is the work of Abraham von Worms, a Jewish traveler who purportedly encountered the enigmatic magician Abramelin during a voyage to Egypt.

Abraham was believed to have lived between the 14th and 15th centuries. The Book of Abramelin the Mage involves the passing of Abraham’s magical and Kabbalistic knowledge to his son, Lamech, and relates the story of how he first acquired such knowledge.

Abraham begins his narration with the death of his father, who gave him ‘signs and instructions concerning the way in which it is necessary to acquire the Holy Qabalah’ shortly before his death. Desiring to acquire this wisdom, Abraham said he traveled to Mayence (Mainz) to study under a Rabbi, called Moses.

Abraham studied under Moses for four years before traveling for the next six years of his life, eventually reaching Egypt. It was in Egypt that Abraham met Abramelin the Mage, an Egyptian mage who was living in the desert outside an Egyptian town called Arachi or Araki. Abramelin is said to have then taught Abraham his Kabbalistic magic and given him two manuscripts to copy from.

One of the highlights of this grimoire is an elaborate ritual known as the ‘Abramelin Operation’, which is said to enable a mage to gain the ‘knowledge and conversation’ of his ‘guardian angel’ and to bind demons.

The manuscript was later used in occult organizations such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and Aleister Crowley’s mystical system of Thelema. Abramelin’s ritual, referred to as “the operation,” is an arduous one.

It consists of 18 months of prayer and purification, which is only recommended for men of sound health between the ages of 25 and 50. Women, in general, are discouraged from undertaking “the operation” because of their “curiosity and love of talk,” although an exception can be made for virgins.

If the tenets of “the operation” are adhered to strictly and with unwavering devotion, you get in touch with your Holy Guardian Angel, who will grant you a wealth of powers. These powers include necromancy and divination, precognition, control of the weather, knowledge of secrets, visions of the future, and the ability to open locked doors.

The book relies heavily on the power of magic squares—unique words arranged into puzzles. Like the Icelandic staves in the Galdrabok, these squares contain mystic and occult properties when written out.

The word “MILON,” for example, reveals the secrets of the past and future when written on parchment and placed over the head, while “SINAH” brings war. The author warns that some magic squares, like “CASED” are too sinister to ever implement.

This text had a profound impact on famed occultist Aleister Crowley, who claimed to have experienced several supernatural occurrences after embarking on the ritual and on the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a 19th-century British magical order. Crowley later used the book as the foundation for his own system of magic.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook