Magical practices still exist today throughout the Muslim world, as in the Middle Ages. They still arouse much interest. Their history is also closely linked to the development of science, Sufism, and Islamic mysticism.

The study of magic makes it possible to apprehend the margins of the Islamic religion. It exposes the practices which escaped the rules elaborated in the strictly religious literature. Esoteric literature is at the junction of scientific (astrology, alchemy, pharmacopeia, etc.) and religious (cosmology, mysticism, prophetic tradition, etc.) literature.

The encompassing character of Medieval Islamic magic practices made it for specific authors of magical treatises, even certain epistemologists, the highest science of human knowledge, and the path to Universal Wisdom (ḥikma).

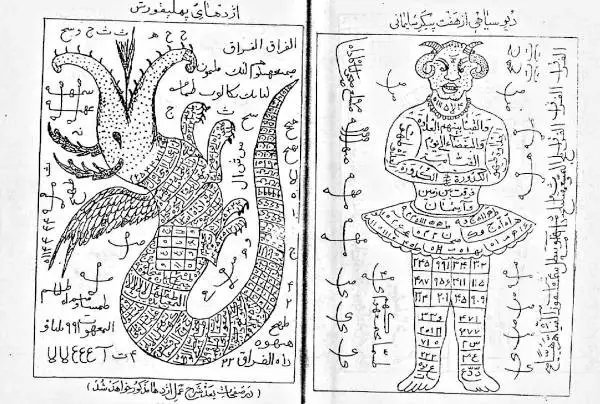

Islamic magic is indeed a complex topic. To develop a comprehensive understanding of magic in medieval Islam, a person would need to understand concepts and disciplines from various fields. These include talismans, amulets, magic squares trickery and conjuring, sortilege, prestidigitation, letter magic, interpretation of dreams, and even astrology and physiognomy.

Ibn Khaldūn, a 14th-century historian, is one of the most authoritative sources on magic in Islam. His writings in the Muqaddimah (“The Introduction”) offer a pervasive account on magic and talismans, defined as (in Rosenthal’s translation):

"A science that shows how human souls can exert influence over the elements without or with celestial help."

Types of Magic in Medieval Islam

In his description of the souls that possess magical abilities, Ibn Khaldūn asserts that they are divided into three groups:

He says the first kind exerts their influence only mentally in the absence of any aid or instrument. The philosophers referred to this as magic (“sihr”).

The second kind uses planetary temperaments and even number properties to influence others. These are called talismans (“ṭilasmāt”). In comparison to the sihr magic, “ṭilasmāt” magic was said to be lesser in strength.

The third type impacts the power of imagination. In philosophy, this was called prestidigitation. Ibn Khaldun dismissed this third type of magic as illusionistic and phantasmagorical. We set it aside for now. Instead, let’s explore the first two primary types of magic.

Based on the literature, the highest form of magic, which would be termed “sihr” in the proper sense, is only possible for those who have supernatural powers at their disposal without the need for instruments.

This preternatural power can either be in the hands of prophets recognized as divine or sorcerers who can access satanic forces.

Prophetic magic is sometimes described as high magic. Sorcerer magic was labeled low magic. The distinction roughly corresponds to the Western world’s classification of white magic and black magic.

The second level of magic requires talismans. It is generally meant to correspond to natural magic since no supernatural power is required here.

Natural magic implies that talismans protect against natural harm and harmful forces, such as earthquakes, wild animals, and different incarnations of the evil eye.

As early as several centuries before Ibn Khaldūn, the brethren of purity Ikhwān al-Safā’ defined sihr as follows in their extended version of their “Epistle on Magic”:

"I must explain to you, my brother, that magic is, essentially, whatever attracts and bewitches intellects and whatever induces the souls to give their consent, obey acceptance, or allegiance through speech and action."

About the time of the Renaissance, the Latin translation of the Ghāyat al-ḥakīm (“The Aim of the Sage”) took the Ikhwani definition of magic and developed it for use, in reality, had a significant influence on Western thinkers.

Until fairly recently, the authorship of several critical alchemical writings, including the Ghāyat al-ḥakīm, and the Rutbat al-ḥakīm (“The Grade of the Sage”), was a mystery.

In 1996, Maribel Fierro succeeded in demonstrating that the author was, in fact, Maslama Ibn Qāsim al-Qurṭubī, who journeyed to the Orient in the middle of the tenth century. Reportedly the Maslama was also the first to introduced the Ikhwān al-Ṣafā’ encyclopedic corpus to al-Andalus.

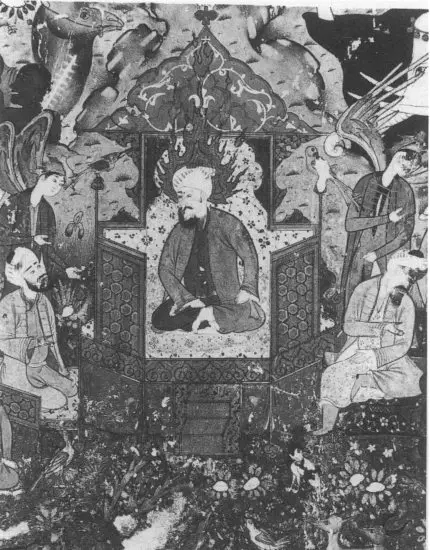

The Ghāyat al-ḥakīm depicts magic as a mysterious art, with impressive rituals that invoke celestial spirits such as planets and asteroids and other sources, many of which have an apparent Oriental background.

Several Arab texts on astrology, alchemy, and magic appear to have formed this collection from the ninth and tenth centuries. And the author boasts of having researched two hundred and twenty-four books on astrology, alchemy, Hermeticism, Ṣābianism, and Ismā‘īlism.

There is a course titled “The Witch Trials” from the Center of Excellence. Click here to see details (Aff.link). You can use our code “LIGHTWARRIORSLEGION466 ” for 70% off.

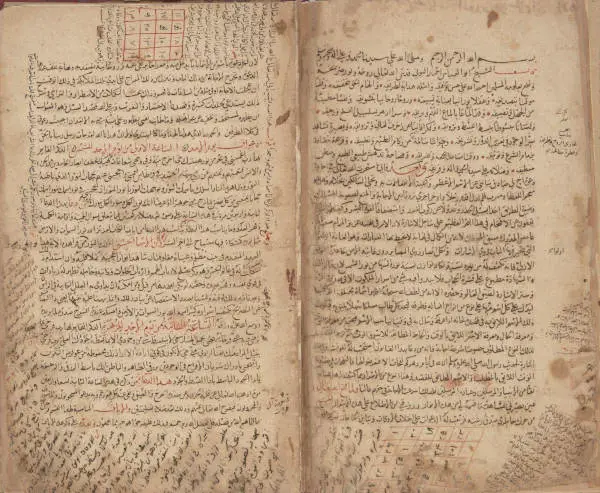

“The Book of the Properties of Letters”

Magic also made up an essential part of medieval Islam, where it was used to interpret the Qur’ān’s words and letters through a science called al-ḥurūf or sīmiyā’.

From the East, one must mention here some of the leading contributors—Jābir ibn Ḥayyān, a famous alchemist from the eighth century and a scholar to whom a vast body of written material was attributed to in classical sources.

Ibn Masarra is to be remembered in al-Andalus. He is an Andalusī scholar noted for his original form of thought whose work Kitāb khawāṣṣ al-ḥurūf has recently been rediscovered. Many years after Ibn Masarra, Ibn’ Arabī, the mystic philosopher, wrote about this science in his Meccan Revelations, one of the most important treatises in the field.

To unravel the full extent to which the science of magic was significant and well-developed in Islam, one must also explore the writings of Ḥājjī Khalīfa. In his Kashf al-zunūn (“The Removal of Doubts”), Toufic Fahd finds 14 magic-related disciplines: natural magic, divination, properties of beautiful names, invocations and unique properties of numbers, conjurations involving sympathy and demoniacs, sacred incantations, evocations of spirit entities, invoking the spirits of the planets, phylacteries (amulets, talismans, philtres), invisibility tricks, fraudulence and deceit, fraud detection, magical spells, and medicinal plants and their properties.

Related Reading: The Witch Stereotype and the Crime of Witchcraft – Opens in new tab

References to Magic in the Islamic Scriptures

In order to understand the stakes of Medieval magic in the Muslim world, it is necessary to analyze the teachings of the Qur’ān and the prophetic tradition of magic ( siḥr ). All theological and legal texts rely on these two sources to elaborate their discourse on Magic.

In Arabic, the word “sihr” (“magic”) has its roots in s-h-r. In the Qur’ān, this word, which means such things as “bewitching,” “enchantment,” “fascination,” and “charm,” appears about 60 times in lexical forms.

“Sihr” or one of its variations appears most frequently in the early chapters of the Qur’ān, where it appears most often in narratives intended to demonstrate that all prophets condemning monotheism have been accused of bewitching their own people.

There is something incredible about the fact that these claims were made indiscriminately concerning Biblical figures, such as Noah, Abraham, and Lot, as well as various Arab figures, such as Hedi, Li*, Shu,amb, and of course, Muhammad himself.

Indeed, as recently seen by Constant Hamès, a Muslim prophet was often referred to by his opponents as “sāḥir” (or “sorcerer”) a title usually associated with words like kāhin (“fortune teller” or “fortune teller”), shā’ir (“Poet”), or majnūn (“idiot”).

Compared to the Meccan period of revelation, Medina’s writings contained far fewer references to magic. However, they contain the essential Qur’ān account of magic, which is given in the second “Sūra.”

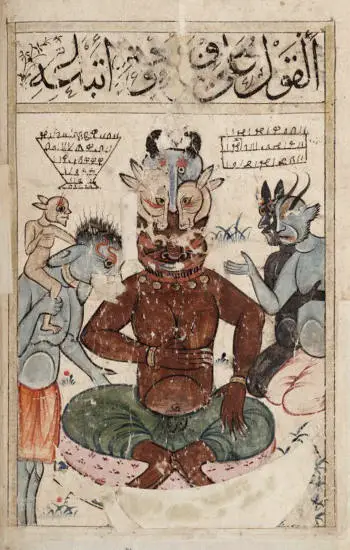

The Qur’ān deals with magic in verse (II, 102) which makes it a teaching of two fallen angels, Hārūt and Mārūt, in Babylon with demons and men. The Qur’ān further indicates that they warned their disciples that magic was a temptation and that they should be careful not to sink into disbelief.

"...But instead, they followed [the words] that the devils said during Solomon's reign. Solomon believed the devils did. The devils taught people magic and the hidden secrets revealed at Babylon. However, the two angels do not teach anyone except when they say, "We are a trial, so don't disbelieve [by taking up magic]."

Finally, the verse asserts that it is only possible for magicians to harm others “only with the permission of God.” This last expression concludes several Islamic magic recipes to remind us that God remains the supreme authority in executing any act of magic.

A second fundamental episode is a fight between Moses and Pharaoh’s magicians mentioned in several places in the Qur’ān. The episode highlights the superiority of divine power over any form of magic.

It is clear that Islamic scriptures do not explicitly condemn nor forbid the use of magic. The Holy Book’s last two “sūras, which are highly regarded, have even been used to explain prophylactic /preventative and other forms of magic on a more practical and popular level.

Also, worth shedding some light on is the wide variety of medieval Islamic literature written on such seemingly magical subjects as the opening letter of Qur’ān, the names of the “Companions of the Cave” in “sūras 18, or the 99 names of God.

An Islamic rereading of the Testament of Solomon, a Greek treatise, tells how Solomon used a ring given to him by the Archangel Michael to summon demons and force them to build the Temple. Although jinns are not demons (but demons can be jinns), Hebrew and Byzantine demonologies have greatly contributed to the development of Islamic jinn conjuring rituals.

Related Reading: “Medieval Witch Trials in Europe”– Opens in new tab

Permitted and Forbidden Magic in Medieval Islam

Despite this, it is also possible to find a much more unfavorable interpretation of magic in Islamic orthodoxy, which has generally been regarded as a mortal threat by the community of believers.

In early Islam, there were prophetic traditions that condemned magic. “The penalty for the magician is the sword,” states al-Tirmidhī, a Sunni Muslim scholar who authored the canonical collection of Ḥadīth in the ninth century.

However, al-Tirmidhī, just after reporting it, questions the validity of his chain of transmission and counterpoint the opinion of Muslim scholars, notably al-Shāfiʿī (767-820), eponymous founder of one of the four Sunni legal schools, going against this hadith and which indicated that the magician not harming others should not be worried. Therefore, the milieu of traditionalists and jurists has a margin of interpretation of the texts sufficiently wide to issue strong condemnations and defend a broad tolerance.

Many of the more theologically orthodox jurists of the past multiple centuries have focused on the dangers of sihr, the same way they alleged magicians, witches, and sorcerers to be demon followers in the Middle Ages. Others were jailed, tortured, or even executed.

Muslims often considered those who practice magic to practice “bid’a” (bad faith), an innovation considered to be heretical. In his infamous “Revival of the Religious Sciences,” Ghazāl categorically states that all forms of magic, including talismans, prestidigitation, and sortilege, are unacceptable sciences.

Nonetheless, even the most traditional jurists and theologians did manage to separate between a permitted form of magic and a forbidden one, with the intention of distinguishing them from one another.

Related Reading: “Church Versus Magic in The Early Middle Ages“ – Opens in new tab

To take up Toufic Fadh’s definition on this point: “what is allowed is natural wizardry, known as ‘white magic,’ including, among different components, charms; nonexistent marvels delivered by common methods, based on properties, having no association with religion or mystic wonders.

Provided no one comes to harm by the use of this magic, natural magic is tolerable. In contrast, magicians who use their magic to cause harm are prohibited. This refers to magicians who resort to demoniacal inspiration (black magic) and the planets’ invocation (theurgy).

As far as modern investigators in this field can tell, the fact remains that the Islamic views regarding magic have always been in direct contrast to those held by traditionalists of the Middle Ages. In many areas of the dār al-islām, magicians, sorcerers, and talisman specialists have continuously performed the actual practices until the present time.

Even the most qualified representatives of legal theory have divergent opinions about this. As an example, the 13th-century Andalusian author Abū’ Abdallāh al-Qurṭubī, one of the most authentic authorities on Harūt and Marūt passages, took a much more tolerant and conciliatory attitude compared to his predecessors.

Furthermore, many of these practices were considered to possess curative virtues, which was undoubtedly another critical reason for their popularity. The legal theory of magic proved particularly harsh wherever magic was perceived as a threat to the believers. But the local magicians who possessed esoteric knowledge were therefore generally respected for helping to benefit the village, so long as they did not breach too many of the forbidden limits. This is evident in most Muslim countries even today.

Do you want to learn more about Magick? Check out our recommendations at “Magick Bookshelf” and many free resources at our “Free Magick Library“

Resources

- Course, Magic in the Middle Ages by Universitat De Barcelona from Coursera

- Ikhwan al-Safa’ – muslimphilosophy.com

- Ikhwan al-Safa’ – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Cornell University Library: https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/witchcraftcoll/

- Book of Arabic Magic (pdf)

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Featured Image: “The Book of the Properties of Letters”